Heading into the first presidential debate in June, Democrats were facing a near-hopeless situation. President Joe Biden had been utterly toxic for more than two years. His administration was so deeply unpopular that Donald Trump, who himself had once been toxic, saw his own favorability climbing toward near-parity. Trump’s argument that the country had been better off under his stewardship, as insane it may have sounded to liberals or anybody who actually remembered 2020, was carrying the day.

The party’s switch to Kamala Harris as nominee was an improvement, but only in relation to the utter desperation of sticking with Biden. For most of Biden’s term, Harris had been even more unpopular than Biden. She was less well positioned to distance herself from the unpopular Biden administration than almost any other Democrat, given her position within it and the need her job created for her to publicly cheerlead her boss.

And so, when Harris began her campaign, Trump was still a decisive favorite:

In the months that have followed, Harris has climbed all the way to parity or is perhaps a very slight favorite. That is to say, the campaign has taken a once-unelectable figure from a deeply hated administration, raised her favorable ratings dramatically, and made her at worst an even bet to win the presidency.

On the right, this success is so dramatic that it has triggered suspicion and paranoia. “The media is fixing the election for Harris” or “The polls are rigged.”

But on the left, the giddiness at escaping certain defeat has given way to existential dread that victory remains far from assured. A wave of recriminations has already begun, largely from the left. The reason Harris is not running away with the election, these complaints insist, is that she is pandering to the center.

“The Harris-Walz ticket is running a campaign rooted in the fantasy that there is a centrist wing of the GOP appalled by Donald Trump,” moans Dave Zirin in The Nation. Many of the complaints zero in specifically on Harris’s moderate messaging. “Democrats have been told to quiet any doubts they had about a parade of cops and sheriffs at the DNC, Harris vowing to maintain the most ‘lethal’ military in the world, or her campaign’s enthusiastic courting of Republicans,” writes Katherine Krueger.

Her pivot toward a hawkish stance on the border “shows that our leading Democrats still don’t know how to do politics; they only know how to react to opponents, allowing the right to set the terms of debate,” argues Felipe De La Hoz in The New Republic. “As president, Trump declared economic war on China, which was then escalated by Biden,” asserts Aida Chavez in the Intercept. “The American people don’t support any of these bloodthirsty policies, but it appears that circles of power in the U.S. are increasingly disconnected from the will of the people.”

One striking commonality in these screeds is the confidence with which they assert public opinion is on the left, and how little they bother to substantiate their belief. “Republicans would sooner gargle kerosene than challenge their own racism and sexism to vote for Kamala Harris. Some of these folks may have been Obama voters, but if they haven’t already become Democrats, they certainly won’t vote for one now,” asserts Zirin. And yet, the latest New York Times poll finds Harris has increased her share of the Republican vote from 5 percent in its last survey to 9 percent now, largely accounting for her slight lead.

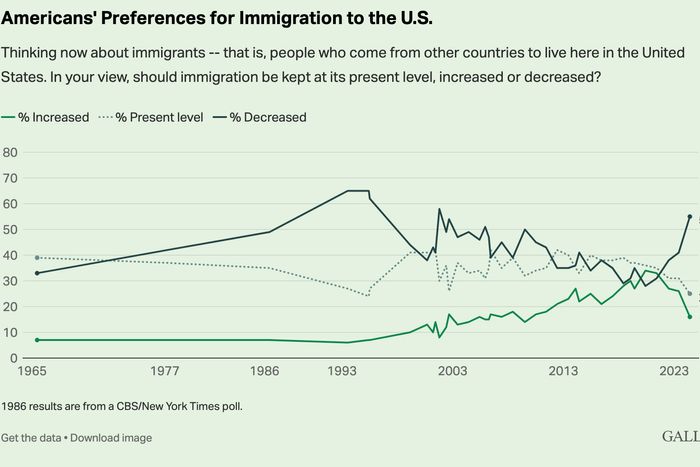

On China, polls show an overwhelming majority of the public sees the PRC as an economic threat. (Just 6 percent of respondents say it isn’t.) On immigration, public opinion has lurched in an overwhelmingly hawkish direction. A border wall and mass deportation — that is, policies that Harris still opposes — now command majorities. The public overwhelmingly wants to reduce even legal immigration:

These polemics take it for granted that their own beliefs are shared by the majority. Zirin, an anti-football crusader, argued earlier this summer that emphasizing Tim Walz’s background as a high-school football coach could cost Harris the election by alienating the crucial bloc of football haters:

This could repel the young, left-wing voters more interested in policy changes than who wins the football wars. Young people care about racism, the economy, climate change, Palestine, and a host of other issues given short shrift at the convention. Football not only won’t be enough to satisfy them. Its embrace may send a signal that the big tent isn’t big enough for them. This championing of conservative symbols like football, in other words, could cost Harris and Walz the election, and it will be their own doing.

If you live in a world in which the voters are clamoring to elect a president who hates the military and police, opposes immigration enforcement, trusts the Chinese Communist Party, and hates football, then the choices made by real-world Democrats are very hard to explain. Indeed, the party’s messaging choices would seem so unfathomable as to defy any rational explanation.

A common thread of the emerging left-wing complaints is that Harris is losing the election deliberately. “This is not incompetence,” suggests Zirin, who observes, by way of explanation, ‘The campaign is clearly afraid of pissing off Zionists — of both the Jewish and Christian variety — and of raising people’s expectations with a bold economic vision.”

The Democrats “have almost all of the advantages but I have seen very little evidence that they are actually trying to win,” argues left-wing commentator David Sirota. “Resistance Liberals don’t believe their own rhetoric about fascism and authoritarianism because they don’t propose any significant political changes,” warns Sam Haselby. “They want to keep the status quo, the conditions which produced the right-wing, but just win an election.”

This form of paranoia has a surprisingly wide and durable appeal to activists on both ends of the political spectrum. In A Choice Not an Echo, the conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly insisted Republicans could easily win national elections if they nominated right-wing candidates and had only been thwarted by the machinations of an eastern Establishment that preferred moderation and defeat (“a small group of secret kingmakers, using hidden persuaders and psychological warfare techniques, manipulated the Republican National Convention to nominate candidates who would sidestep or suppress the key issues”).

Ideologues often have difficulty accepting the fact that the public does not always agree with them on everything. The Manichaean mind assumes all truths are perfectly evident and can only be opposed by either pure ignorance or pure evil. The idea that anybody holds beliefs that equivocate between good and evil, or stranger still, subscribes to a mix of both, is foreign, especially if they surround themselves with fellow true believers.

Public opinion oscillates over time, often in direct opposition to the direction pushed from the White House. This dynamic, which political scientists call “thermostatic public opinion,” has had unusual force during the Biden presidency, where a surge of inflation and border crossings have yielded a powerful backlash. The public is in a reactionary mood.

Harris ought to be losing. That she isn’t owes a great deal to the buffoonery of her opponent. But it can also be attributed to the cleverness and unsentimental courtship of the center her campaign has followed.

For all the complaints his stance on Israel drew from the left, Biden generally avoided criticism from the left on his broader campaign themes. That is why progressives remained loyal even as he was drifting toward inevitable defeat. Harris has violated progressive shibboleths, doing almost everything within her power to meet the decisive handful of persuadable voters where they are. However depressed progressive activists may feel as she has moved toward the center, the country as a whole has not coincidentally grown dramatically more favorable toward her:

Will it be enough? That is hard to say. But the inverse relationship between the mood on the left and Harris’s standing with the electorate as a whole is no accident. It is the fruit of a well-executed strategy that has created an even chance of victory out of certain defeat.