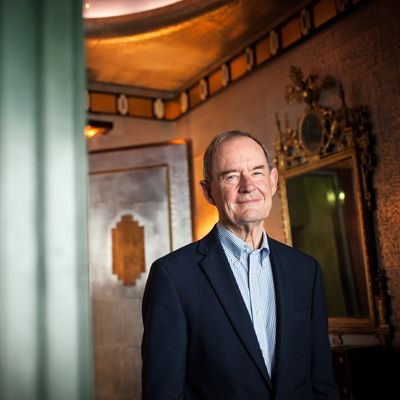

David Boies at his Manhattan apartment in 2018.

Photo: Kholood Eid/The New York Times/Redux

It is a Wednesday afternoon, and David Boies sits in the back seat of his rubellite-red Mercedes S 580 idling outside the Hudson Yards office of his law firm. It’s a deep back seat, dark leather, shaded windows. Boies, 83, had just walked out of a morning-long arbitration, and he looks tired. “I have a 96-hour day,” he tells me. It is just after noon. Boies is on his way to Vatican City to meet Pope Francis — but first he has to stop at his home in Armonk to get his luggage. I am along for the ride.

The driver shifts the car into drive, then turns left on West 35th Street toward the green glass of the Javits Center. In the front sits Boies’s wife, Mary — an antitrust lawyer at the firm — wearing a green baseball cap and a blue windbreaker. Outside, it is warm and cloudless, a good spring day to stop working in a conference room and hit the road. Boies announced in December that this year would be his last as the chairman of Boies Schiller Flexner, a position he has held since its founding in 1997 — and about six years longer than he had originally planned. Boies is, officially, still BSF’s chair until December, but his successor, Matthew Schwartz, is now running the firm day-to-day: “We’re going to Denmark and Sweden next month and then October — where are we going, sweetheart, in October? Japan? No, no, no — the bike trip. Bordeaux! Bordeaux. We have a trip to Japan and Taiwan in the fall, but that’s not for biking.”

By an accident of timing, Boies had started retirement-planning back in 2016, before two of his star clients at the time, Hollywood producer Harvey Weinstein and blood-testing company Theranos founder Elizabeth Holmes, were convicted of different crimes — Weinstein, of raping women in New York and California, and Holmes, for defrauding investors. (Weinstein’s conviction in New York was recently overturned on appeal, but he will likely stand trial again). His continued representation of both harmed, or at least complicated, his public image. The Boies story, until then, was that of an Illinois-born lawyer who had overcome dyslexia to argue some of the most important cases of the past 50 years: gay marriage in California and, on behalf of the federal government, the antitrust case against Microsoft’s web-browser monopoly. Even his failures were noble, as in Al Gore’s failed 2000 bid over the recount of the election in Florida before the (largely Republican-appointed) Supreme Court, which ended up deciding the election in George W. Bush’s favor by 537 votes. But it wasn’t just Boies’s unsavory clients that weighed on his reputation — when it came out that he had hired Black Cube, an Israeli private-investigations firm that tricked and followed reporters, that revelation cost him his job representing the New York Times. He was also widely seen as being a bit too aggressive in attacking The Wall Street Journal’s reporting on Theranos’s fraud. (Boies, who didn’t represent Weinstein in his criminal rape trials, has admitted to making a mistake in hiring Black Cube.) In the aftermath of all that bad press, the firm shed about 300 lawyers, but former partners have told me that internal politics played a bigger role in that exodus than Boies’s image problems: an ill-fitting merger with a California firm, expensive new offices, and power struggles among partners among them. Former partners have told me that some of Boies’s clients, including victims of Jeffrey Epstein, were chosen in part to rehabilitate his image. (Boies has, in fact, represented Epstein victim Virginia Giuffre since 2014.)

As the car heads north, I ask about the cases against Donald Trump. At the time, Manhattan district attorney Alvin Bragg’s hush-money case against Trump was still ongoing, and a jury convicting the former president on 34 counts was far from certain. Three other cases — around January 6, holding on to top-secret documents, and racketeering in Georgia — are all unlikely to reach trial before the November election. Boies is a major Democratic supporter, donating millions of dollars directly to candidates, state Democratic parties, and political action committees. He once employed Hunter Biden — though the president’s son apparently never came into the office. But he also said in 2018 that he would be open to representing the former president in his investigation by Robert Mueller. “This long, drawn-out morality play isn’t in the country’s best interests. It needs to be resolved. Of course, he’d have to agree to do what I told him,” he told James B. Stewart of the Times.

Boies twists his torso toward me, bringing his face just a few inches from mine: “First of all, I think the hurdle to sue a former president ought to be pretty high.” He slows his argument, choosing each word. It isn’t that Bragg doesn’t have a case, Boies says, but that the legal and political repercussions probably aren’t worth it. “The idea of prosecutors in one party criminally prosecuting a former president of a different party is something that, except in really unusual circumstances, is better left to other countries.”

I ask about the three other cases. The day before our interview, Judge Aileen Cannon had indefinitely delayed the trial over Trump’s handling of classified documents at Mar-a-Lago. At first, Boies says, these cases are different from the New York suit, but then he seems to change his mind. “I don’t think there’s any doubt that there was a technical violation of the law with respect to the documents,” he says. “We know that a lot of other high-ranking government officials also technically violated that law. Now, was Trump’s violation more egregious just because he didn’t effectively give everything back, or his lawyers give everything back, the way it appears most of the others did? That may be. Is that a reason to bring a criminal prosecution? Eh, I don’t know. I haven’t thought that through entirely.”

“What about January 6?” I ask. Last August, Trump was indicted on three charges of conspiracy and a charge of obstructing an official proceeding — criminal charges that stem from his incitement of a mob of thousands of supporters who stormed the Capitol in 2021. January 6, Boies says, was “a tragedy”: “The attack on the Capitol — the threats to the seat of democracy — was outrageous and indefensible.”

“Was it a crime?” I ask.

“Certainly,” Boies says. “The people who did it —”

“Does that include Trump?”

“I think that’s much more complicated,” he says. “You have to distinguish between what I would describe as culpable conduct and what you would describe as criminally culpable. He should have accepted the results. There was no relevant fraud in the election. I think his advisers knew that. Rather than contributing to divisiveness, he should have tried to contribute to healing, to bringing people together.”

“Let me ask the question this way,” I tell him. “If the federal government asked you to prosecute Donald Trump, would you take the case?”

Boies pauses, then flicks his tongue behind his bottom lip and briefly looks out the window. For 22 seconds, he does not answer. “To be honest,” he says, “I hope not. But it would be a hard case to turn down because it would be such an interesting thing to participate in. I’d like to think I would have turned it down because I’m dubious about criminalization of that conduct.”

“What conduct?”

“Making the speech,” he says. “I don’t think that there’s any evidence that he formulated plans with the people who did it. He didn’t call people into the Oval Office or instruct his people to organize an attack on the Capitol.”

It is at about this point that Boies qualifies his comments. He doesn’t have all the facts, and he could be wrong. The slate of fake electors — part of Trump’s alleged plan to overturn the 2020 election — is, in his mind, the best case for criminal conduct. “The question is whether Trump can be sufficiently tied to it to be criminally prosecuted, and that is a case I might very well take on,” he says. “But as I understand it, he’s really being prosecuted for his public remarks.” He worries that the case could have serious repercussions for free speech. “Think about the phrase you hear over and over again by speakers just before and just after riots, where people are killed and buildings burn: ‘No justice, no peace,’” he says. “Now, is that an incitement to riot? When people talk about how evil police are, ‘Kill the pigs’ — is that an incitement? Sometimes people do go out and do that. Now, is the speaker responsible for that? I think that takes us down a complicated and dangerous path.”

We arrive in Armonk after about an hour. His son and grandson, both named David, are waiting in the driveway. Mary invites me inside while the Davids Boies discuss that morning’s arbitration. On the vestibule walls are dozens of pictures of him with his children and grandchildren; in a back corner, a terra-cotta warrior, imported from China, crouches with a dark cape draped around its neck. Soon, Boies comes into the house, and we continue our interview in a small library overlooking his backyard.

A little more than a week had passed since Columbia University called in the New York Police Department to clear anti-Israel student protesters from a campus building, Hamilton Hall. “They had to,” he says. In the 1960s, Boies had, in fact, represented members of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the civil-rights-era group that included Marion Barry, John Lewis, and Stokely Carmichael. He was also a treasurer for groups raising money on behalf of the Chicago Seven, the activists — including Abbie Hoffman and Students for a Democratic Society co-founder Tom Hayden — who were acquitted of rioting during the 1968 Democratic National Convention. “In 1968, people were trying to speak out. They weren’t trying to silence other people,” he says. I ask if he’s ever felt silenced by the left, especially over his representation of Weinstein. He has not, he says. “Reputation is something that is external. I don’t think it affected my reputation with clients. It didn’t affect my reputation with judges. And it didn’t affect my reputation with people who know me. I think that, probably, there were some people who didn’t know me that it had some effect.”

Since this interview, I’ve thought about this answer and what Boies was meaning to say. Although I have occasionally reported on his cases during the past decade, and have talked with him off the record a few times, I wouldn’t say I was someone who knew him. And yet, in January, a package arrived outside my Brooklyn apartment with two bottles of wine in a pine box and a note. “Happy holidays,” it said. It was signed “—David.” (I returned it. His spokeswoman, Dawn Schneider, later claimed responsibility for the gift.) Many more people don’t know Boies than those who do know him, though. “It’s easy to be simple if you don’t take into account all of the facts. What’s hard is to take into account everything so it can’t be attacked and yet make it understandable,” Boies tells me. We had been talking about one of his firm’s cases then, but it was a form of a classic Boiesism that can apply well outside the courtroom. Over the years, I’ve heard some variation of this from current and former BSF lawyers, as if it were a firm mantra.

Afterward, Boies shows me around the house a bit, and we make some small talk in his backyard. There’s a pool, a new building under construction, and, if you look closely enough, giant black statues of a gorilla and lion he got after coming back from a safari. (He bought them from a place in Rhode Island, he tells me, not Africa.) I ask what he is going to see the pope for. Boies is semi-churchgoing, he tells me, and though he’s Presbyterian, he’s “interested in the same things.” There will be a convocation with other leaders — Eric Adams among them — and they’ll talk about, he thinks, “how we ought to be,” though he’s not really sure. On the schedule is a large dinner, then a private audience, then a concert. He starts to excuse himself, to get ready for his flight, and turns to go back indoors. I had been wondering if he might be going out there to drum up some business. “Would you ever represent the pope?” I ask him offhandedly. “Sure,” he says. “In a minute.”

Source link