This article appeared in the September 26, 2025 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

After the Hunt (Luca Guadagnino, 2025)

My attention should have been elsewhere. During a scene in a tandoori restaurant in which philosophy professor Hank (Andrew Garfield) confides in his department colleague and friend Alma (Julia Roberts) about sexual assault allegations that have been made against him, I couldn’t help but stare at Hank’s open messenger bag. Specifically, at the empty three-ring binder inside the bag, blue, either 1.5” or 2”. Hank is animated, defensive, and too loud. Alma watches him carefully. She does not eat. But why isn’t there anything in the binder? I kept wondering. Is that what he is bringing to teach?

The binder, I decided, suits Hank quite well. He is empty and arrogant, a recognizable type of younger professor (in jeans and with an exposed tuft of chest hair) within the rarified world of Yale, at least as Luca Guadagnino imagines it in After the Hunt. And Guadagnino’s Yale has a lot in common with the version of elite universities Christopher Rufo and other right-wing crusaders have railed against. It is rich, elitist, and insufferable, even if its left-liberal politics are dialed very far down. Don’t get me wrong. Whether any of this resembles the “real Yale” is unimportant—though most of the film was shot in England, with Cambridge standing in for the New Haven university’s gothic exteriors. But neither should you mistake the film for a serious drama with real-world concerns. After the Hunt doesn’t seem to have been developed very far past the “Yale mood board” stage. The furnishings may be elaborate, but the characters and their conflicts are less so. It is, in short, a fantasy of the place it attempts to depict, and a flimsy one at that.

Atop this world sits Alma, who is something of a queen, admired by everyone around her. Naturally, the only direction for her to go is down. Her star graduate student, Maggie (Ayo Edebiri), worships her and possibly desires her as well. Hank is openly flirtatious, and Alma’s psychoanalyst husband Frederik (the always-wonderful Michael Stuhlbarg) puts up with all this, mostly gracefully. After a party at Alma and Frederik’s shockingly large and opulent apartment, Hank walks Maggie home, and, as Maggie later recounts to Alma in a tearful stairwell confession, he sexually assaults her. At least this is what she tells her mentor, whose reaction is less than sympathetic. Meanwhile, Hank indignantly maintains his innocence. Alma, who has so far enjoyed both Hank and Maggie’s flattery, seems almost offended that either of them would turn to her for help. A predictable crisis of cancel culture, #MeToo, race, and privilege spills into her lap, until it engulfs her too.

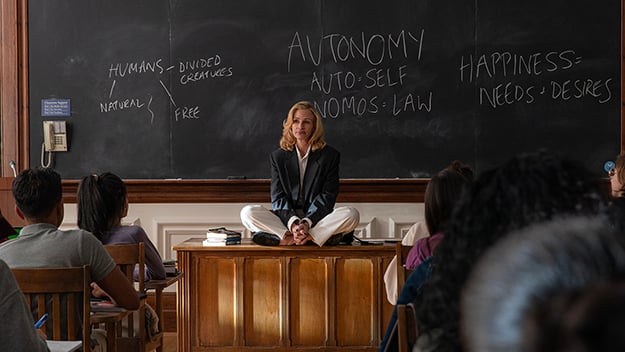

It takes a lot to turn America’s sweetheart into a frosty bitch—and Alma uses an even harsher word to describe herself. Roberts manages it handily. Her wide smile is transformed into a tight-lipped grimace; her auburn mane, now blonde with dark roots, is twice-dyed and carefully coiffed. Though the entire cast gives outstanding performances, including a nearly unrecognizable Chloë Sevigny in a shaggy Prince Valiant bob as the university psychiatrist, Roberts is the focus. She is on screen for nearly every second of the film, giving us ample time to study her hard, porcelain face, which gives us nothing but diffidence, irritation, and, as the film goes on, raw contempt.

Guadagnino is mostly uninterested in the work that professors do, so none of the film’s intellectual references make much sense. There is plenty of name-dropping, but it’s meant to conjure an air of sophistication, and perhaps buffoonery. “Aristotle was a xenophobe!” “Freud was a misogynist!”—these one-liners, neither funny nor insightful, are what count for banter in Alma’s circle. I found a scene in which Alma tries to teach Theodor Adorno’s Minima Moralia in a graduate seminar especially unpleasant: Alma, by now clearly unraveling, upbraids an Asian student named Katie (Thaddea Graham). “Bullies” is the better word. Until this point, Katie has not said a word, but she braves an interpretation of the text, pointing to Hannah Arendt’s reading of The Odyssey, particularly a moment in which the hero Odysseus comes to understand something about himself when he hears someone else singing about his endeavors. Alma unleashes some jargony nonsense about “the Other.” Katie falls back into silence. She knows she’s touched a nerve.

Alma does not want to see herself from the outside; she is comfortable only within, and ideally within the confines of the philosophy department. Insularity hardly begins to describe it. In certain close-up shots, the depth of field of cinematographer Malik Hassan Sayeed’s camera is so shallow that half of a face appears out of focus. The outside world scarcely touches Alma’s. “Don’t you have some obscure protest to be publicly angry at?” she spits at Maggie’s partner, whom she also continually misgenders. For a while I thought this might be a period film, with the Woody Allen–style title cards and the giant blazers rolled up at the sleeves (like the identical outfits that Roberts and Amanda Seyfried wore at this year’s Venice Film Festival). Then I saw a cell phone.

This being a Guadagnino film, you might be wondering what kind of sex Alma is having. The answer is none, apparently. The only thing she seems to desire, other than power, is the junk food that she eats at her desk (props to the box of Bonchon). There’s a cheap joke when Alma finds Frederik snoring to internet porn and a couple of crumpled tissues, but at least he got off! If all the lead characters had been male, it seems unlikely the film would have remained so sexless. “One [thing I’m very knowledgeable about] is the love between men,” Guadagnino once said in an interview with Fantastic Man Magazine, “and the other is the erotic tension that’s underlying any relationship between two men, gay or straight. Given the right circumstances, any straight man can bond relentlessly with another man, and maybe even more deeply than with a woman.” Maybe the problem, for him, is imagining how women can “bond relentlessly” with anyone at all.

However weak and castrated, the men in After the Hunt lead richer lives than the hyper-ambitious women around them. (At one point Alma attends a lecture titled “The Future of Jihadism is Female,” which I’m not sure is meant to be taken as satire.) Frederik listens to Miles Davis, modernist music, and reggae, and he cooks a beautiful cassoulet, which Alma mocks. Even Hank, in the middle of a tantrum, spares a moment to spout Shakespeare. Meanwhile, on Alma’s bedside table lies an overturned copy of Thomas Mann’s Buddenbrooks and a couple of pills. She reaches for the pills. And Maggie, dressed like Alma, studies her mentor more closely than her Agamben (whom she allegedly plagiarized for her dissertation).

Alma is a difficult character to like, but she’s impossible not to watch. She is like a beautiful tentpole for a decadent flea circus. Maybe this is what Hank means when he refers glibly to a “crisis in higher education”: not the very real culture war against affirmative action and DEI, or the dismantling of humanistic inquiry in favor of STEM fields seen as more practical and exploitable—but, like in Mann’s Death in Venice, an old order in an advanced state of decline. Perhaps this is why Alma’s nails are painted a glossy black, to suggest rot. But they also look great.

Guadagnino has little of Mann’s ambivalence. He enjoys luxuriating in this airless world, with its bountiful red wine and tasseled pillows. The dean of humanities admits as much in one of the movie’s clunkiest lines: “I found myself in the business of optics, not substance.” It’s unclear if the vapidity of such a statement is a fault of the institution or the filmmaking. Another movie might have entertained the cynical—and to my mind entirely justifiable—view of places like Yale where scandals never really rock the university, offenders receive light penalties or even fail upward, and the structure of power remains ultimately unchanged. But if Guadagnino is attempting critique, it would land harder if his film were not such a sloppy depiction of what an Ivy League (or really any American) university is actually like. I have small quibbles, like the curious absence of tweed, or the question of why such an esteemed professor like Alma has not yet secured tenure. But seriously, where is the Title IX office in all of this? Or Yale itself, with its not-so-secret societies and its steady stream of U.S. presidents, Supreme Court justices, and people who in no small part run the world? Are the binders empty because the professors are full of shit, or is it just a continuity error?

Guadagnino has expressed an interest in adapting Buddenbrooks, and I would welcome an interpretation from this restless, omnivorous director. I only hope, however, that he spares its characters the fate he gives to Alma. One of the things that makes Mann’s novel truly great is a scene in which a character comes alive reading philosophy—Schopenhauer, to be precise. For several pages, the world seems new to him. He is profoundly moved. Then he gradually sinks back into the slow, dull life he had been living before. If only Alma, too, could be excited by an idea, something from the outside, unexpected. Even for a moment, that might be enough to justify all the misery.

Genevieve Yue is an associate professor of culture and media at The New School, and the author of Girl Head: Feminism and Film Materiality (Fordham University Press, 2020).

Source link