This article appeared in the September 12, 2025 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

Cover-Up (Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus, 2025)

There’s something strangely sedating about being at the Venice Film Festival. The annual Mostra Internazionale d’Arte Cinematografica takes place not in Venice proper, but on a tiny island called Lido that’s a 15-minute ferry ride from the mainland. For a New Yorker like myself, if Venice feels like a simulation, with its paved, car-free roads, picturesque canals, and historic facades, Lido feels like an idyll beyond the edge of the world. Formerly a “balneotherapy resort” and spa town, the island is suffused with humid languor—even with all the hubbub of the festival, which brings over 100,000 visitors to a community of about 20,000 people, it feels sparse and slow. I listened for the chimes of the church clock to decide when it was time to walk over to a screening. I took naps in my apartment between movies. I cooked my meals with groceries purchased from little mom-and-pop stores once I realized that getting food after 10 p.m. was a near impossibility.

If this is all very relaxing, it is also somewhat numbing, and the awards-aspiring, star-studded, formulaically plotted titles that crowd the festival’s Main Competition don’t help. Be it Paolo Sorrentino’s opening film La grazia, in which Toni Servillo plays an Italian president wrestling with a euthanasia law (and the disapproval of a dreads-sporting Black pope), or Yorgos Lanthimos’s Bugonia, a sordidly unhinged thriller about two QAnon-pilled incel types who kidnap a Sackler-esque CEO, or Kathryn Bigelow’s insipid A House of Dynamite, which tracks the inner machinations of the U.S. government’s war room as a nuclear missile (deployed by a conveniently unidentified enemy) hurtles toward the country, many of the Competition narratives seemed to strain for real-world relevancy but unfolded like playhouse fantasies: broadly characterized, gratingly self-indulgent, and lacking meaningful stakes. (Jim Jarmusch’s Golden Lion–winning Father Mother Sister Brother and Guillermo del Toro’s Frankenstein were two exceptions—the former for its beautifully perceptive and witty exploration of filial ties, the latter for its unabashedly operatic embrace of Mary Shelley’s existentialism.)

Perhaps this is why the films that I cherished the most at this year’s festival were predominantly from the non-Competition sidebars, and nonfictions of some kind or another, piercing through Lido’s illusive bubble with lightning bolts of reality. Exhibit A: Laura Poitras and Mark Obenhaus’s documentary Cover-Up. The movie is about the famed and dogged American investigative journalist Seymour Hersh, although “about” feels like the wrong preposition here. Several of Poitras’s films take off from the life and work of a person—Edward Snowden, Julian Assange, Nan Goldin—but only as a structuring principle to explore ideas and issues of broader social and political import. Her documentaries evade the two grating contemporary trends in nonfiction—the celebrity bio-doc and the montage-heavy issue film—to get at something far more alive and affecting: a sense of how individuals locate themselves within history.

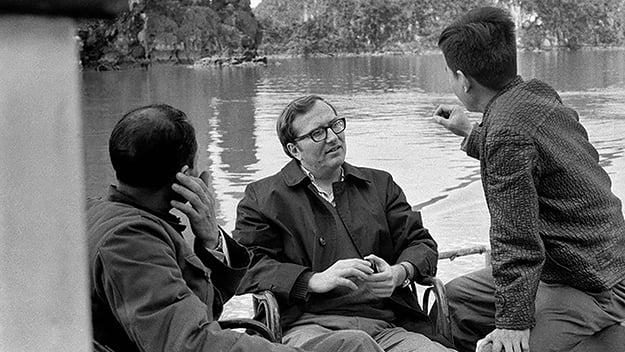

In the case of Hersh, this history is long and difficult. Sy, to those who know him, began his career as a speaker of truth to power by reporting on the 1968 Mỹ Lai massacre in Vietnam, where American soldiers brutally murdered hundreds of unarmed children and adults—sometimes, after raping and mutilating them—under the pretext of fighting the Viet Cong. Cover-Up begins with Hersh recounting how that scoop came about, underlining that it didn’t require much in the way of hardcore detective skills: the facts were there in plain sight, but no one had taken the initiative to investigate or report them. This confrontation with passivity and complicity becomes a through line connecting the many stories—the litany of state-sanctioned crimes—that Poitras and Obenhaus have Hersh walk us through, including Operation CHAOS, the CIA’s secret program for spying on student protesters in the 1960s; the Watergate scandal; and the dark revelations of Abu Ghraib.

Poitras and Obenhaus’s style is simple and direct, and stealthily polemical. Though Hersh’s story is primarily told through archival materials and interviews, we glimpse intermittent scenes of him speaking with a source in Gaza about the killing of children by the Israel Defense Forces; the rhyme with Mỹ Lai is hard to miss. During the interview segments, Poitras’s voice is frequently heard gently probing the prickly Hersh, who is fearful of exposing his sources and hesitant to make a film that centers him instead of his subjects; only briefly does he comment on his personal life, his marriage, or his children. There is a remarkable sincerity in his effort to resist the individualizing and valorizing that reduces historic and systemic struggles to simple, hero-villain narratives—an effort foregrounded by Poitras and Obenhaus’s direction and editing. I walked out of the film in awe of Hersh, but more importantly, reminded of the long fight for justice that precedes our present and must continue unabated into the future.

Lucrecia Martel also balances the long view and the short view, history and the individual, in Landmarks (the Spanish title, Nuestra tierra, translates “Our Land”), her first feature documentary. The film takes as its starting point the murder of 68-year-old Indigenous activist Javier Chocobar in 2009, during a confrontation with police and a landowner attempting to evict members of the Chuschagasta community from their ancestral lands in Argentina’s Tucuman province. Though that incident was captured on video, it took nine years for the case to reach the courtroom; the killers were convicted and detained but released in 2020, due to the court’s delays in considering their appeals. Martel follows the legal proceedings of the trial, which involves public hearings and reenactments. But she is careful to expand her lens beyond this one incident, which, slowed down and complicated by the legal system, threatens to obfuscate the chronic and ongoing injustice of colonialism in Argentina.

Martel and her co-writer María Alché dig deep into the history of the land’s colonization and ownership, detailing the various thefts and sleights of legal hand that form the scaffolding for what may seem like an isolated act of violence. The significance of their approach is illustrated in one crucial moment, when the defendants in court cite an article by a writer claiming that the Chuschagasta community became extinct in 1807. Martel interviews the writer, who is shocked to realize that his work has real-world consequences; he says he just wrote something to “add flair” to an article about an auction, and that if he had to research the pieces he writes daily, he “would die.” At stake is a battle for collective memory, and Landmarks makes clear that archives are structures, designed to privilege certain communities over others.

Some may find the middle sections of the film, in which Chuschagasta community members are interviewed about their family histories, surprisingly straightforward for a filmmaker known for her audacious stylistic experimentation. But this directness reinforces the impression I had of the film at large: that this is a movie invested in committing to the record lives that are frequently, purposefully erased. These scenes are a forceful counterpoint to the official proceedings, where documents, deeds, and laws serve as the means for a state to enforce its hegemony. In one gesture of poeticism, drone shots pervade the film, evoking surveillance, but also the ghostly feeling that the land precedes any of the people we see onscreen—that it stood witness to lives that came before even the state of Argentina.

The violence inherent in the supposedly neutral workings of bureaucracy—its tyranny of rules and procedures—is also the focus of Tunisian filmmaker Kaouther Ben Hania’s The Voice of Hind Rajab, which won the festival’s Grand Jury Prize. Hind Rajab was a 5-year-old Palestinian girl whose relatives were shot and killed by the IDF in January 2024, when they were trying to evacuate Gaza by car. Rajab was trapped in the vehicle amidst their dead bodies and called the Palestine Red Crescent Society from a cell phone for help. The utterly gutting recordings of her conversation with Red Crescent staffers, in which she begs them to come rescue her while they helplessly seek permission for an ambulance to be sent to her aid, form the heart of Ben Hania’s film. The director uses the real audio of Rajab’s phone call, but reconstructs the scenes that unfolded at the Red Crescent call center with actors. The movie unfolds like a doomed chamber drama, where the end comes slowly but surely: the ambulance was mere feet away from Rajab when soldiers gunned down the little girl along with two rescuers.

The film generated skepticism among many critics, and for good reason. Ben Hania worked with Rajab’s mother and family to make the film, and yet, dramatizing the murder of a child—just one among so many that continue to be killed in an ongoing massacre—bears the stink of exploitation, a feeling reinforced by the film’s participation in a glitzy competition at a major European film festival. Many Hollywood stars and filmmakers added their names to the movie as executive producers, including Rooney Mara, Jonathan Glazer, Joaquin Phoenix, and Brad Pitt, which has prompted people on social media to wonder why Rajab’s mother has still not been evacuated from Gaza. I carried these reservations with me into the film, and though the movie didn’t allay them all, I came out genuinely moved by Ben Hania’s approach.

Focusing on a single incident or victim often serves to provoke sensationalistic pity instead of critique, because a limited perspective can obscure systemic injustices in favor of emotionally heightened experiences. But as with Landmarks’s depiction of the Chocobar case and Cover-Up’s account of Sy Hersh’s reporting, The Voice of Hind Rajab induced the opposite response in me. The film is sparse and simple, putting us in the Red Crescent call center in real time as the staffers, played by actors, attempt to assuage Rajab’s fears while trying to coordinate a rescue. This coordination is brutally complex: the Red Crescent has to inform the Red Cross, who in turn have to get permission from the Israeli military to open a safe route for the ambulance. Despite the rescuers only being an eight-minute drive away from Rajab, this process takes hours, and then proves to be futile.

This is the terror of the law in plain, unflinching view. In the name of protocol (and what a twisted protocol it is, to have to ask the people shooting up your community for permission to save one of their victims!) governments and their militaries get to inflict violence, so that when they’re called out for it, their response can be that they followed all the rules. I appreciated The Voice of Hind Rajab for illuminating this reality so concretely, and I hope it will affect all of its viewers as viscerally as it did the audience I saw it with. As to its real-world effects, who can say? Cynicism is built into the film, as it is in Landmarks. These movies acknowledge that the modes of resistance available to us, including cinematic and artistic modes, are forced to engage with the same systems that disenfranchise us. They can rarely save lives—most of the time, they can only memorialize them. Whether we greet them with more than just awards and applause is up to us.

Source link