This article appeared in the August 1, 2025 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

By the Stream (Hong Sangsoo, 2024)

A lot happens in Hong Sangsoo’s latest, By the Stream. After a few features in which his plots seem to have been reduced to the barest minimum—like the beautiful sister-films In Water (2023) and In Our Day (2023), as well as the Isabelle Huppert–starring A Traveler’s Needs (2024)—Hong surprises us here with a baroque narrative made of multiple storylines. It’s as if he takes a certain delight in frustrating the expectations of both his acolytes and his detractors. Just when we think we know his M.O., he slips away from us—not unlike Michel Simon’s title character at the end of Jean Renoir’s Boudu Saved from Drowning (1932)—and leaves us with a new film, strikingly different from the last.

Packed with details, By the Stream takes place across five nonconsecutive days, punctuated by five mornings and four lunar phases. The film follows Jeonim (Kim Min-hee), an art teacher at a women’s university in Seoul who witnesses and sometimes intervenes in the lives of multiple characters swirling around her. The action opens in the wake of a scandal: a male student (Ha Seong-guk) is canceled by his fellow classmates and fired from his position as the director of the end-of-semester play for simultaneously dating three female cast members without their knowledge. Jeonim, as the faculty member in charge of the theater project, hires her uncle, Sieon (Kwon Hae-hyo), a well-known former actor who now runs a bookstore, to complete the production with the four remaining students in the 10 days that are left before its premiere. Across several conversations, we learn that Sieon was blacklisted by the industry, although the exact reasons remain ambiguous.

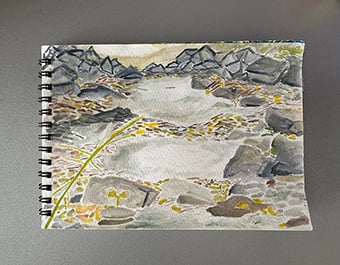

During these 10 days, Professor Jeong (Cho Yun-hee), the head of the department, becomes more and more enamored with Sieon. Also, at the start of each day, Jeonim (who at one point describes having a stigmata-like “mystical experience”) is seen painting watercolors by a stream that passes near the school. Meanwhile, the moon transforms from crescent to full, the student actors rehearse with Sieon, and the various storylines flow together as the three primary characters—Jeonim, Sieon, and Professor Jeong—converse over beer, wine, soju, and platters of grilled eel. We never find out much about the central figure, Jeonim, except that she is a weaver and that her watercolors are possibly a form of inspiration for her large-scale textile works. As a kind of instructor-weaver-narrator, Jeonim channels and unifies the various fugitive plot threads.

Hong himself paints each of the characters in what could be described as syncopated brushstrokes and contrasting colors. The film is densely plotted, but some crucial events are elided. The students’ minimalist play is performed in full for us in one scene, but we never learn why the perturbed president of the school initiates an inquiry into it. After the canceled director reconciles with one of the female students, Sieon takes him aside to have an intimate conversation with him that is out of earshot to us—we can only infer its content. And what to make of Jeonim’s tale about her mystical experience, involving tears of blood streaming from her eyes for three consecutive days? Does she think of herself as a saint? These narrative gaps carve out a mysterious side to each character and produce a space for our speculation.

By the Stream could be called a “river film”—a subcategory of Rivettean origin. River films possess a sense of narrative drift caused by the intersecting paths of autonomous storylines, each associated with a different character—tributaries running into a major waterway, with parts of some hidden by others. It is a contradictory form that emerges from dispersion and fragmentation, but which nevertheless gives the impression of an organic unity.

The river film is never a clear and crystalline surface, whether due to its muddiness or its blinding reflection. We can never grasp all aspects of the characters or the story at any given moment, because the narrative never stops rushing forward. Instead, portraits remain unfixed, as potentialities that are forever expanding. There is always the surprising introduction of paradoxes that complicate our full understanding of the figures on screen. I’m reminded of Paul Cézanne’s paintings of apples: like Hong’s characters, they’re not only interactions of colorful strokes or simple lines that define a shape, but a constantly shifting balance between the two.

My favorite mystery in By the Stream appears in the final minutes (don’t worry, dear reader: Hong’s films are far too good to be spoiled by me). Earlier, we’d seen one of Jeonim’s textile works, dominated by a bluish gradient that references the constant movement of the Han River. Jeonim had told her uncle that each successive weaving traces the current from the river “backwards up the streams.” In the film’s last segment, after a 10-minute-long shot at a riverside restaurant (which we’re told serves great grilled eel), Jeonim excuses herself from Sieon and Professor Jeong and goes down to the stream. She enters nature, and we lose her. She escapes from her companions, and then from us.

Hong’s films invite us to summon the little narrative detective within ourselves and complete the story with him. Here, I imagine that Jeonim goes up the mountain and out of our sight to find the source of the stream. This is the one day in the film that she doesn’t begin by painting next to the creek. I see her up on the mountain, painting a watercolor of the confluence of river and stream—the motif for her next textile project. While we all ponder Hong’s enigmas, I leave you now to finish my own version of Jeonim’s watercolor. I invite you all to watch By the Stream and paint your own.

Matías Piñeiro is an Argentine filmmaker living in New York. He is an associate professor at Pratt Institute and a recipient of a 2025 Guggenheim Fellowship.

Source link