When Deputy Provost Marshall Silas Soule left his home late in the evening of April 23, 1865, to investigate reports of gunfire, he did not know it would be his last day on earth. Perhaps he was thinking of Hersa, his wife of twenty-two days, as he patrolled the streets of Denver. Maybe he was rethinking his recent testimony before a Congressional committee investigating the Sand Creek Massacre in southeastern Colorado. Maybe his thoughts focused on his duties as Denver’s newly appointed territorial law enforcement officer. Regardless of his thoughts, he walked the streets, drew his weapon, turned a corner, and confronted a gun-waving man named Charles Squier and his companion, Williamson Morrow.

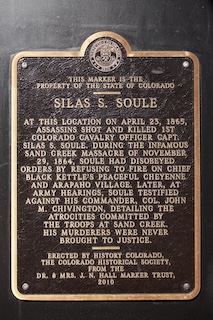

Soule fired first, wounding Squier in the arm. Squier’s bullet struck Soule in the face and lodged in the back of his brain, mortally wounding the young Provost and ending the promising career of an idealistic, charismatic, and courageous officer. Squier escaped and was later captured but was never convicted. Morrow disappeared forever. No one was ever brought to justice for the death of Silas Soule.

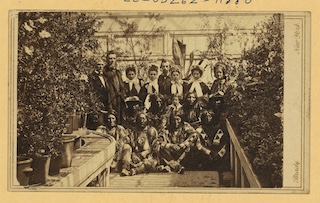

Before touring History Colorado Center’s exhibit, The Sand Creek Massacre: The Betrayal That Changed Cheyenne and Arapaho People Forever, in Denver this summer, I had never heard of Silas Soule. I knew the massacre was one of the worst atrocities committed against native people by the United States Army during the Indian conflicts of the late 19th century. I did not know the pretext for the attack, nor did I know that two officers, Silas Soule and Joseph Cramer, refused to engage their troops in the attack. Many of their fellow officers, including their commanding officer John Chivington, considered Soule and Cramer cowards and traitors for refusing to fire on Indian women and children. Those feelings may have led to the murder of Silas Soule.

The story of the Sand Creek massacre is a tragic but familiar one of broken promises, cultural misunderstanding, political ambitions, rumors, racial hatred, poor communication, and greed. It is a story of attack, retaliation, and revenge. It is an all too familiar story of white settlement encroaching on native land in numbers too large to resist.

In the 1851 Treaty of Fort Laramie, vast portions of Colorado and Nebraska were set aside for the Cheyenne and Arapaho people. But after gold was discovered near Denver in 1858, white settlers flooded the region seeking their fortunes. Congress established the Colorado Territory in February 1861. The Treaty of Fort Wise of 1861 reduced the Cheyenne/Arapaho lands to one-third of their original size. Yet nothing stopped settler encroachment on the Cheyenne and Arapaho land.

Most of Colorado’s white settlers and their leaders did not understand tribal government. When they negotiated with a tribal leader, they assumed that leader possessed the power to enforce treaties. The reality was very different.

Plains Indian Tribes such as the Cheyenne and Arapaho were not united under a governing alliance. For example, the Cheyenne and Arapaho were enemies of the Comanches and Kiowas. They could not submit to Territorial Governor John Evans and his militia commander John Chivington’s insistence that they surrender their weapons unless the Kiowas and Comanches did the same. And no Cheyenne or Arapaho leader had any influence over the Kiowas or Comanches.

Indeed, even respected chiefs like Black Kettle of the Cheyenne and the Arapaho chief Left Hand could not dictate surrender for all of their own warriors. A significant group of Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors did not accept the treaties of 1851 and 1861. Known as the Dog Soldiers, they left Black Kettle and Left Hand’s bands and formed a distinct band unwilling to surrender to the American calvary. The Dog Soldiers raided several white settlements, once killing a family of four. White settlers were either unwilling or unable to recognize that a renegade band of Cheyenne and Arapaho had committed the atrocities— not the warriors under the leadership of Black Kettle and Left Hand.

Sensationalist journalism by William Byers, owner of Denver’s Rocky Mountain News, fueled white fears. Byers and others spread rumors that local tribes were allying with one another to launch an attack on Denver. This fearmongering led the Colorado Territory’s Governor, John Evans, to issue a “shoot on sight” order to the Colorado militia. Any Colorado calvary officer encountering Indians, even an Indian traveling alone, was to execute them immediately, regardless of whether they were sighted on native land or elsewhere.

Other Cheyenne and Arapahos were tired of fighting. Buffalo were disappearing from their traditional hunting grounds, and their people were hungry. Black Kettle and Left Hand sent emissaries to Fort Lyon, CO, to express their willingness to surrender in exchange for the Army’s protection, along with provisions of food and other supplies. Major Edward (Ned) Wynkoop ignored the order to shoot every Indian he saw. He agreed to meet with the Native leaders and convinced his superior officer to give Black Kettle and Left Hand’s bands a chance at peace. Black Kettle and Left Hand’s people were told they would no longer receive rations from the Army but should seek land on which to hunt near the Army’s protection. So, they settled along Sand Creek, approximately 20 miles from Fort Lyon, where they could safely hunt for food. They were given an American and white flag and told to wave the flags if they saw US Calvary.

The divisions between peaceful and warlike bands within native tribes mirrored the feelings of the white population of Denver. Some, like Major Wynkoop, Silas Soule, and Joseph Cramer, saw the distinction and argued for a flexible response: to attack warlike Indians but leave those seeking peace alone. Others, like former Methodist Minister John Chivington, thought all Indians posed a threat to white settlement in Colorado. Chivington was granted permission to organize a new calvary regiment, the 3rd Colorado Calvary.

Chivington received Governor Evans’s permission to countermand Wynkoop’s peace efforts and march on the encampment at Sand Creek. He marched in secret and arrived in Fort Lyon on November 28, 1864. Colonel Chivington ordered the fort closed. No one was allowed to enter or leave the fort before the attack. The Indians were not to be warned. He would launch a surprise attack the following morning, and there would be no mercy. Soule protested. He told Chivington that “any man who fires on those Indians is a cowardly son of a bitch.” Chivington threatened to cashier Soule and promised to see him hung. Despite Chivington’s threats, Soule ordered his men not to fire when the attack began and moved them to a safe position from which they could observe the attack.

Chivington praised the outcome of the Sand Creek attack, which he called a battle and not a massacre. He claimed he inflicted heavy casualties on a well-armed group of warriors. An estimated 230 Cheyenne and Arapaho were murdered. However, the vast majority of them were women and children. The citizens of Denver welcomed Chivington’s propaganda. They cheered as the soldiers paraded through the streets carrying scalps and booty claimed from the victims.

After the assault, Soule wrote his mother and his friend Major Wynkoop and described the horrors he witnessed at Sand Creek.

“The massacre lasted six or eight hours, and a good many Indians escaped. I tell you Ned it was hard to see little children on their knees have their brains beat out by men professing to be civilized’” wrote Soule. “One squaw was wounded, and a fellow took a hatchet to finish her, … One squaw with her two children, were on their knees begging for their lives of a dozen soldiers, … when she took a knife and cut the throats of both children, and then killed herself. … Some tried to escape on the Prairie, but most of them were run down by horsemen. I saw two Indians hold one of another’s hands, chased until they were exhausted, when they kneeled down, and clasped each other around the neck and were both shot together. They were all scalped, …. They were all horribly mutilated.”

Soule’s account circulated throughout Denver. Some soldiers were ashamed of what happened and began telling others what they witnessed. Others, tongues loosened by liquor, bragged about their actions. A military investigation heard testimony from Soule, Cramer, Wynkoop, and natives that survived the attack. The investigators concluded Chivington knew “of their (the Indians at Sand Creek) friendly character, having himself been instrumental to some extent in placing them in their position of fancied security,” yet “he took advantage of their in-apprehension and defenseless condition to gratify the worst passions that ever cursed the heart of man.” Today, the descendants of the Cheyenne and Arapaho people of Colorado continue to testify to the horror of November 29, 1864, and commemorate the events with a Healing Run from Sand Creek to Denver. The run is meant to “heal the land and heal the spirit” of the people who died that day. The City of Denver honors the calvary officer who refused to fire on innocent people. A historic plaque stands at the site of Silas Soule’s murder. Courage comes in many forms. Sometimes, it dwells within the heart of a soldier who disobeys orders. Sometimes, it dwells in a people’s long struggle to survive and thrive.

Ray Tyler was the 2014 James Madison Fellow for South Carolina and a 2016 graduate of Ashland University’s Masters Program in American History and Government. Ray is a former Teacher Program Manager for TAH and a frequent contributor to our blog.