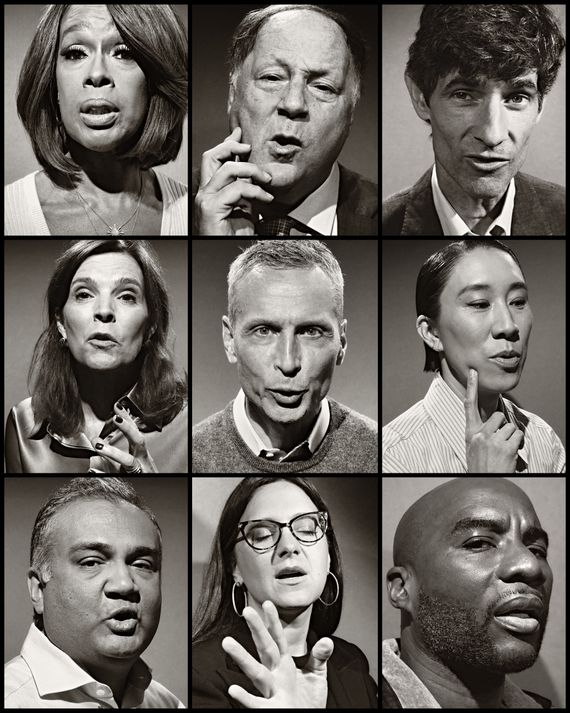

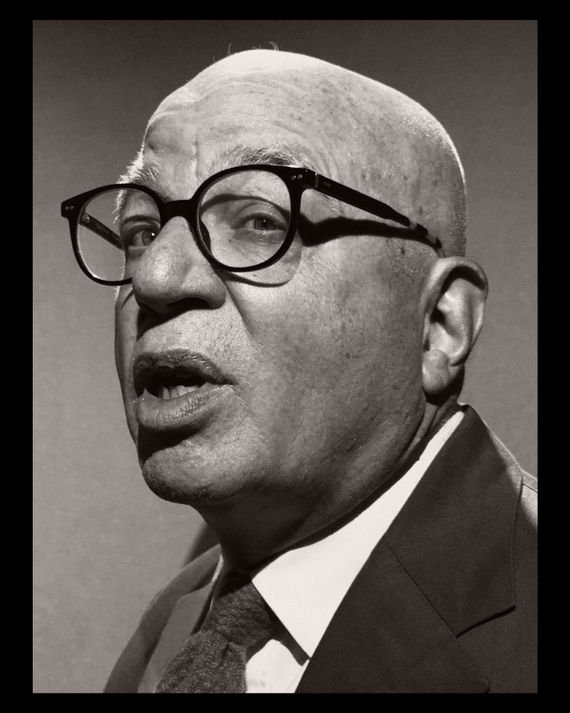

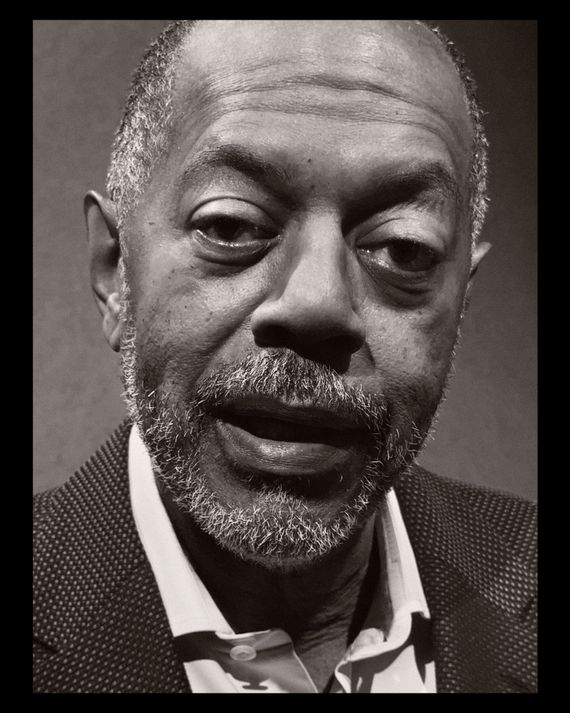

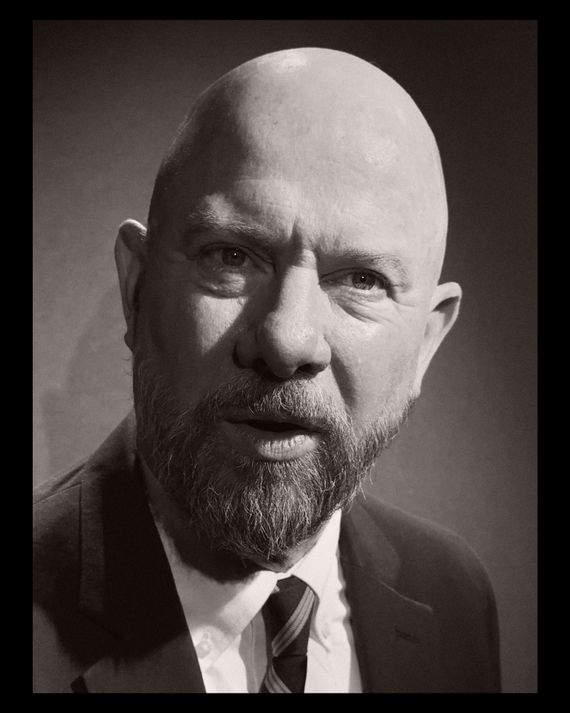

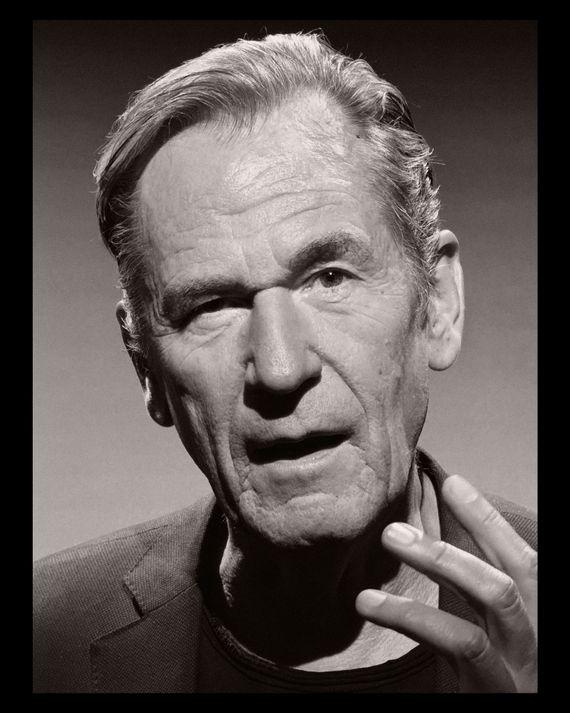

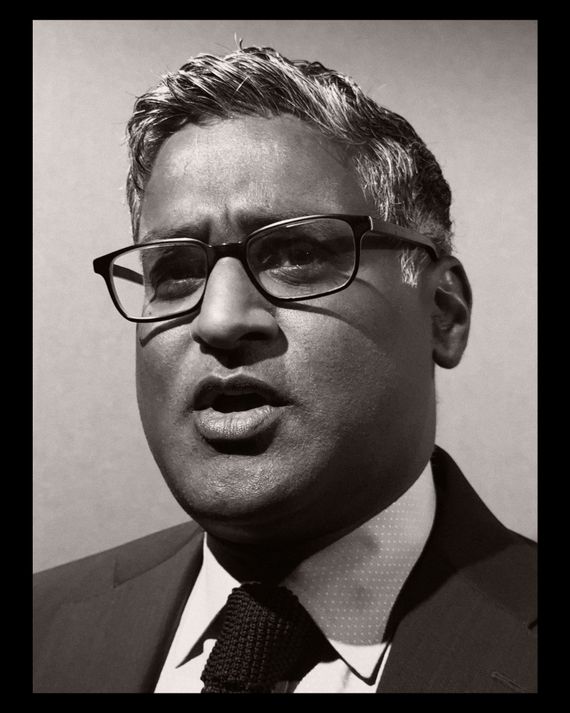

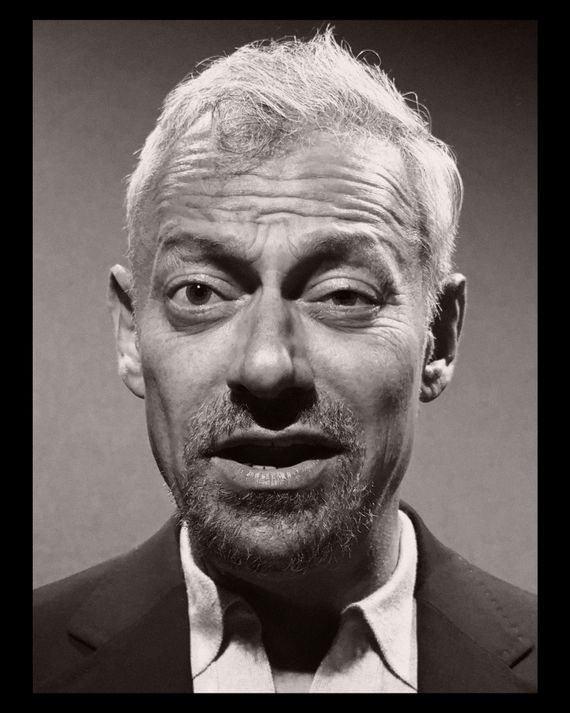

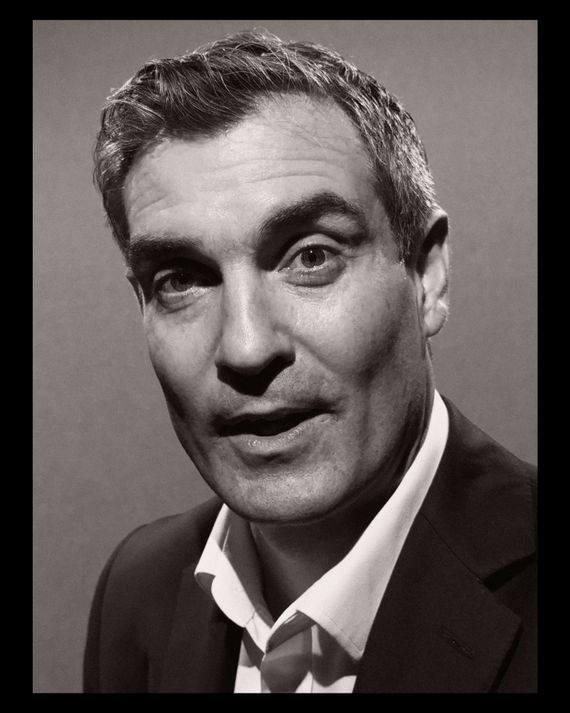

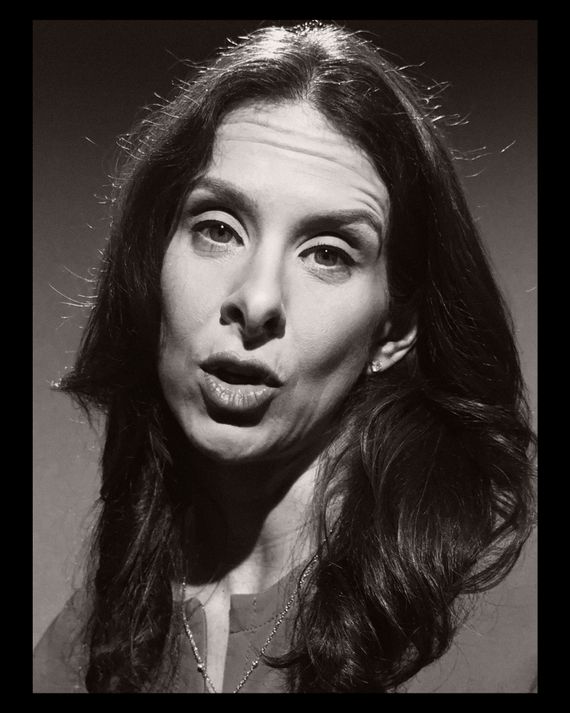

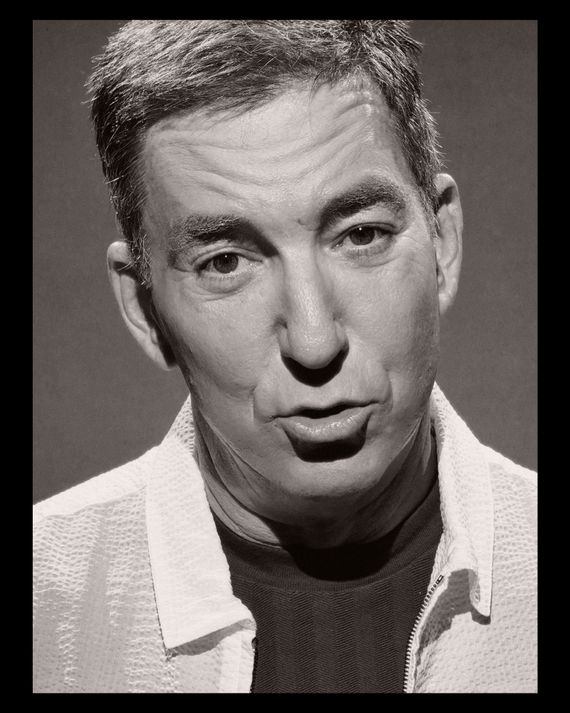

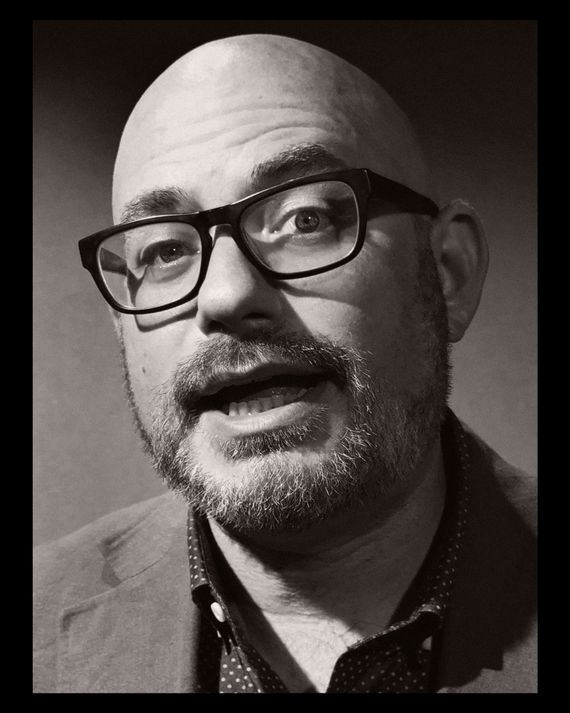

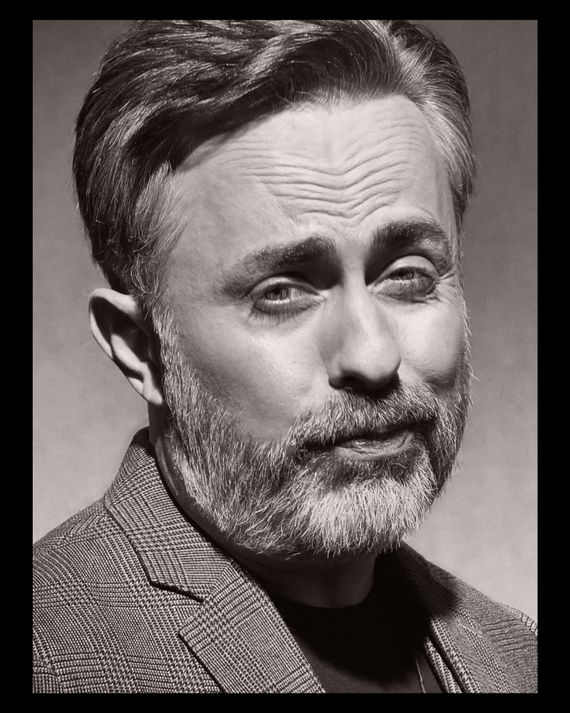

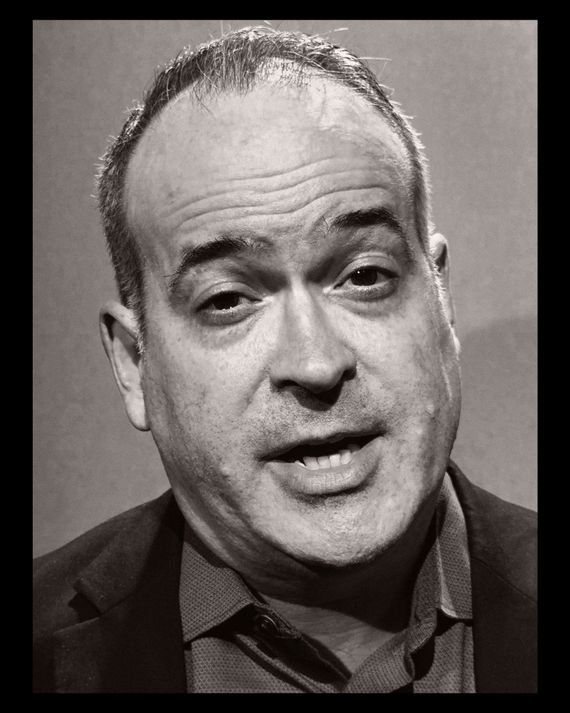

Imran Amed, founder and editor-in-chief, The Business of Fashion. | Willa Bennett, editor-in-chief, Cosmopolitan and Seventeen. | Jeremy Boreing, co-founder and co-CEO, The Daily Wire. | Graydon Carter, founder and co-editor, Air Mail. | Sewell Chan, executive editor, Columbia Journalism Review. | Leroy Chapman Jr., editor-in-chief, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. | Charlamagne tha God, co-host, The Breakfast Club. | Eva Chen, vice-president of fashion, Meta. | Joanna Coles, chief creative and content officer, The Daily Beast. | Kaitlan Collins, anchor, CNN’s The Source. | Sam Dolnick, deputy managing editor, the New York Times. | Mathias Döpfner, CEO, Axel Springer SE. | Stephen Engelberg, editor-in-chief, ProPublica. | Bryan Goldberg, CEO, Bustle Digital Group. | Emily Greenhouse, editor, The New York Review of Books. | Glenn Greenwald, host, System Update; co-founder, The Intercept. | John Harris, co-founder and global editor-in-chief, Politico. | Radhika Jones, editor-in-chief, Vanity Fair. | Almin Karamehmedovic, president, ABC News. | Jon Kelly, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Puck. | Lauren Kern, editor-in-chief, Apple News. | Gayle King, co-host, CBS Mornings. | Jessica Lessin, founder and editor-in-chief, The Information. | Hamish McKenzie, co-founder, Substack. | Wendy McMahon, president and CEO, CBS News and Stations and CBS Media Ventures. | Kevin Merida, former executive editor, the Los Angeles Times. | John Micklethwait, editor-in-chief, Bloomberg. | Janice Min, founder and CEO, Ankler Media. | Neal Mohan, CEO, YouTube. | Matt Murray, executive editor, the Washington Post. | Samira Nasr, editor-in-chief, Harper’s Bazaar. | Mel Ottenberg, editor-in-chief, Interview. | Bill Owens, executive producer, CBS’s 60 Minutes. | Jonah Peretti, co-founder and CEO, BuzzFeed, Inc. | Jimmy Pitaro, chairman, ESPN. | Ramesh Ponnuru, editor, National Review. | Keith Poole, editor-in-chief, the New York Post Group. | Betsy Reed, editor, The Guardian US | Alison Roman, writer and chef. | Maer Roshan, co-editor-in-chief, The Hollywood Reporter. | Carolyn Ryan, managing editor, the New York Times. | Ben Shapiro, host, The Ben Shapiro Show; co-founder, The Daily Wire. | Sam Sifton, assistant managing editor, the New York Times; founding editor, New York Times Cooking. | Bill Simmons, founder and managing director, The Ringer; head of podcast innovation and monetization, Spotify. | Ben Smith, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Semafor. | Andrew Ross Sorkin, founder and editor-at-large, the New York Times’ DealBook; co-anchor, CNBC’s Squawk Box. | Simone Swink, senior executive producer, ABC’s Good Morning America. | Jake Tapper, anchor and chief Washington correspondent, CNN. | Nicholas Thompson, CEO, The Atlantic. | Emma Tucker, editor-in-chief, The Wall Street Journal. | Jim VandeHei, co-founder and CEO, Axios; co-founder, Politico. | Bari Weiss, founder and editor, The Free Press. | Will Welch, global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork. | Gus Wenner, CEO, Rolling Stone. | Michael Wolff, author. | Matthew Yglesias, writer, Slow Boring; co-founder, Vox.com. | Jeff Zucker, CEO, RedBird IMI.

When this magazine revived the annual “Power Issue” last year, we assembled a list of secretly powerful New Yorkers in an effort to explain how the city actually works. This year, we were curious to understand how the news media is surviving in a time of imploding business models and record public distrust. We gathered 57 of the most powerful people in media — and rather than simply anoint them, we put them to work. What follows is a tour through the state of journalism, assembled from dozens of hours of extremely candid conversations.

Some executives we spoke to are in the business of keeping legacy institutions like the New York Times or the Washington Post viable; some are trying to build new media companies like Puck, The Ankler, or The Free Press; some are sole proprietors of their own brands via newsletters or audio. We focused largely on the news media: the organizations and individuals responsible for producing and distributing information to the public, whether it concerns politics or fashion or sports. And because news organizations are obviously no longer the only places — or, in some cases, even the main places — people get their news today, we didn’t look just at traditional news outlets. We also included people like Neal Mohan, head of YouTube, the platform where zoomers are increasingly likely to get their news, and Lauren Kern, head of Apple News, essentially the world’s largest newsstand.

All of these media insiders have watched up close as the business that undergirds journalism changed dramatically in the past decade, and almost all of them would agree that it hasn’t, for the most part, been for the better. We wanted to understand not just what this new state of media looks like but what the future of getting reliable news out in the world might actually be. Which news organizations are struggling most to find their footing, and which seem to have figured out how to find an audience? Can any of those companies get people to pay for their journalism? What’s the point of print? Are Facebook, Google, and X the enemies of the press or still, somehow, its salvation? What happened to the industry that scaled up to manufacture clickbait? And who’s going to train the next generation of journalists? Is getting 9,000 steady paying readers better than trying to reach a mass audience? And can anyone besides TikTok and Facebook even reach a mass audience these days?

Some unquestionably powerful figures declined to participate, and to avoid the obvious conflicts, we didn’t include any current employees from, or any conversations about, New York or its parent company, Vox Media. We also allowed those who spoke to us to be anonymous as often as they wished since our driving interest was in having genuinely honest conversations with people important enough that they can’t always be candid when quoted by name.

One question that emerged was whether any organization or individual has the ability to influence culture or shape perspectives as was once common in this business; that role today seems to rest more with social platforms and search engines, as well as the singular figure of Elon Musk. Our sources struggled to identify how power in the media works now. It’s not that no one has power anymore, but their reach is increasingly narrow and threatened by the rapidly eroding agreement over the facts.

Still, we found a lot of optimism about the media business and its future. Even those who are gloomy about the state of the industry see a lot of good work being done in their own shops and those of their rivals. As one editor-in-chief impishly put it, “Everyone who’s not having fun and just doing 20th-century stuff is so boring. It’s too much work to not have fun in it. The media universe will keep transforming, and some changes will be for the better. Five years from now, we’ll all be different because it feels like we’re on the cusp of some crazy new thing.”

The Advertising Business | AI | Air Mail | Apple News | Axios | Jeff Bezos | The Bosses | A Brief History | CNN.com | Condé Nast | Covers | Entry-Level Journalists | Facebook | Google | Local News | The Los Angeles Times | Media Gossip | Media Moguls | Rupert Murdoch | Elon Musk | Newsletters | The New York Times | Print | Puck | Punchbowl News | The Scoop Business | Semafor | Subscriptions | Substack | TV News | The Wall Street Journal | The Washington Post | Who Controls the Media? | YouTube

“Collapsing as always, I’m reliably told.” — Ben Smith • “Going to hell in a handbasket. There may be, down the road, a way out of it, but I just don’t know what it is.” — Graydon Carter • “Like the fire swamp in The Princess Bride. It is treacherous in places, you could go up in flames, you could be attacked by a rodent of unusual size, but you can be a little bit of a pirate and anticipate those threats and figure out how to defuse them.” — Radhika Jones • “It’s in flux, and the small and strong will survive.” — Janice Min • “I don’t feel like employees understand how precarious it is at all.” — Carolyn Ryan • “Going to look very different over the next five years than it did for the previous 50.” — Jeff Zucker • “I think you’d have to be crazy to begin a career in journalism right now.” — A media executive who knew better than to say it on the record

“We lost our business model because of the internet, which everybody knows, but not for the reasons they think. It was simply that the tech companies built a better advertising model and we weren’t able to respond quickly enough. The newspapers lost their classified ads, the local newspapers lost their monopoly on distribution for certain regions, and the magazines lost their monopoly on distribution among different interest groups. If you wanted to, 20 years ago, sell golf balls, you bought an ad in Golf magazine; now, you buy a Facebook ad targeted to people who have re-upped their golf-club memberships. So there just was a better way of advertising. And we did not see that at the beginning of this tech revolution. We were so excited about infinite free distribution we didn’t see that the whole premise of the business model that supported this thing was getting undercut relatively quickly. We didn’t respond appropriately and didn’t build the right business models quickly enough. Then by the time we did, most of us had our lunch eaten. What is one main way The Atlantic and other serious publications drive subscriptions? They buy ads on Facebook.” — Nicholas Thompson, CEO, The Atlantic

“One brand-new thing in the teens was this fantasy that you could become tech-rich off journalism. Certain places began playing a scale game, thinking they could get a toehold against Google and Facebook. Of course, to grow as fast as they thought they would need to, they decided they had to take venture money — that felt like, We want to be a tech company, and we’re going to do what tech people do. It had shades of WeWork, trying to tell a story about yourself that investors could get behind while raising money, when really you’re doing what everyone else is, which is pretty straightforward: making content and trying to sell sponsorship against it. Then everyone got underwater. I liken it to everyone who got an easy mortgage on a home in 2007 not knowing they were already in default.” — Janice Min, founder and CEO, Ankler Media

“Nobody wants to be in a position where their company is overwhelmingly reliant on any trillion-dollar entity for distribution or monetization, right? That’s just a very vulnerable position to put your business in. There are plenty of recent examples of companies that learned the hard way.” — Jon Kelly, editor-in-chief, Puck

“I was very hopeful that the big tech platforms would see us as very complementary. There was an amazing ten-year run of a symbiotic relationship and then the social platforms got powerful and strangled a lot of the companies that were the most focused on making content for them. It was painful for us. We are finally on the other side of this shift and building our business on direct traffic. But it was a death sentence for some of the publishers that were really focused on getting their audience from Facebook.” — Jonah Peretti, CEO, BuzzFeed

“Google really undermined professional journalism when they moved away from PageRank. It’s one thing to place less emphasis or weight on authority. It’s another to actively harm those publishing houses that have reputations and authority. And I think that they spent the past ten years seeing how far they can push their monopoly and what they can get away with. What they found is they can get away with a great deal.” — Bryan Goldberg, CEO, Bustle Digital Group

It’s pretty simple, explains Bloomberg editor-in-chief John Micklethwait: “You produce good content; you get people to pay for it; the money you get from those people paying for it, you produce more good content. If you don’t have a system whereby you have consumers paying for your content, then you are generally in a perilous state.” It helps that many people use Bloomberg’s content to direct their investment decisions, so they will definitely pay for it. But his larger point stands for everyone building a paywall. “The business no longer is ‘You want to sell a couch? We’ll charge you a lot of money to reach every one of our readers,’” says ProPublica’s Stephen Engelberg. “It’s now ‘Do you want to have the journalism that keeps democracy alive? Would you be willing to pay $10 a month?’” Not every outlet charges, of course. But if you can persuade readers to subscribe, you’ve created a more direct model for making money off them. “Subscription revenue is the important business metric,” says an editor-in-chief. What’s unknown is how many subscriptions readers will pay for. “A sustainable business model for journalism is going to need people willing to pay for five or seven or ten new subscriptions instead of one or two,” explains Columbia Journalism Review’s Sewell Chan. “The Times or The Wall Street Journal presumably, or maybe CNN if they’re wildly successful, is spot No. 1. And everybody else, from Vanity Fair to the Miami Herald, is competing for spot No. 2. That’s not sustainable for our industry.”

To many, the most instructive failure of 2024 was The Messenger, an all-things-to-all-people news site run by ex Condé Nast and People executives with a “chief growth officer” formerly of Gawker Media. It planned on building out a 550-person newsroom and flooding the internet with viral scoops but instead burned through most of its $50 million in funding within a year and shut down. “I’m always suspicious when someone has a huge splashy launch saying they’re going to get up to 300 million page views in six months and reach a massive national audience,” says Betsy Reed, editor of The Guardian US. “I just feel like you can’t do that out of the gate. You need to have a much clearer grasp of who you’re reaching and why you’re going to be relevant.” What actually has succeeded this year are operations — many of them run through Substack — that have low overhead and a focused appeal. Some longtime media executives find this new world befuddling. “I’m surprised that people are okay with the subscription model, where they don’t have that many listeners or viewers but are making money, so they’re just good with it,” says one of them. “The Substack writers, people with Patreon podcasts. My generation was wired completely differently. We wanted to be read or listened to by as many people as possible. And now this new generation is like, I’m totally cool with having 9,000 die-hard fans.”

The Congress-focused media company Punchbowl News, which was founded by Politico veterans Jake Sherman and Anna Palmer in 2021, is well read inside the Beltway. “It’s so small and it’s so particular, and yet it seems like it has impact,” says Carolyn Ryan of the Times. “I don’t even know how many reporters they have — it feels like just a handful — but they really seem to have a sense of mission and what value they bring.” That value is priced at $350 a year — a lot for a general reader, but, as with Politico Pro, such subscriptions are often treated as a business expense by anyone with a need to be in the know. “Instead of them being like, Okay, this newsletter is designed so that 10 million people will open it and read it,” says The Daily Wire’s Ben Shapiro, “they’ve designed a letter that’s meant for 10,000 people to open and read it but to pay a higher rate in order to do that.” (There have been reports that the Washington Post is looking at buying it, which the Post denies.)

Apple News has essentially created an iPhone-based newsstand with actual human editors culling news from a variety of sources for its users, some of whom pay for access to journalism that publishers offer only to subscribers. “It’s going back to a very old-fashioned skill of human curation of what you’re going to highlight,” says The Ankler’s Janice Min. “It’s a little bit like the legacy-media jamboree.”

The editorial program is run by Lauren Kern, a former editor at New York and The New York Times Magazine. Her team spotlights features as well as breaking news stories, “narrowing down the best possible source of information at that particular time” in order to figure out, as Kern puts it, “how we reach the broadest possible audience with the best possible information.”

“Apple News provides a huge lift to our stories,” says Betsy Reed. “We reach this vast audience that otherwise we wouldn’t achieve on our own.” “If you’re a small publisher,” says Sewell Chan, “Apple News is like a godsend. It’s free traffic.”

Publishers behind the Apple News+ paywall also get paid in a system a bit like Spotify’s. All those monthly fees get pooled, and a portion is allocated to publishers based on how many minutes people spend on their stories. (The monthly rate works out to a few cents for every “engaged minute” an article attracts.) This Apple money has recently grown to be a significant contribution to many outlets’ overall business — and one that, they calculate, more than makes up for any direct-subscription revenue it cannibalizes.

What’s to stop Apple News from turning off the spigot? Not much. “I think there’s a lot of media businesses that are relying on Apple News right now and probably in too much of a way,” says Rolling Stone’s Gus Wenner. Like other relationships with tech companies that go awry, “it’s a double-edged sword: It can be good, but it’s out of your hands and it can get pulled away.”

With cable fees under pressure from cord-cutting, CNN CEO Mark Thompson, who previously was responsible for building the paywall around the New York Times, has introduced a subscription plan starting at $3.99 a month. If even a fraction of CNN.com’s 150 million unique monthly viewers choose to pay, the plan would provide a windfall. Will what worked for a newspaper work for cable news?

“If he can find a way to package video for consumer subscribers, then that’s interesting. The evidence so far is that it’s gone the other way around: The people who’ve got successful subscription models tend to be print people who’ve added video as part of that,” says an editor. “So there is a suspicion that to make a consumer-news thing work, you need to have a version of what we used to call ‘print’ in it.”

“All eyes are on Mark Thompson and what happens at CNN, in part because of how he overhauled the Times, and he seems like somebody who might try something a little bit more daring. He’s also got more at stake,” says a TV executive who notes that while CNN’s ratings and advertising are having problems, “it also has tremendous global resources, and how could it find different ways to deliver what people want? I mean, that’d be pretty exciting to watch and see.”

But not everyone is expecting much. “They haven’t figured out just fundamentally what they’re for, what their use is,” says one pessimistic editor-in-chief. And their past experiments have failed spectacularly. Remember CNN+?

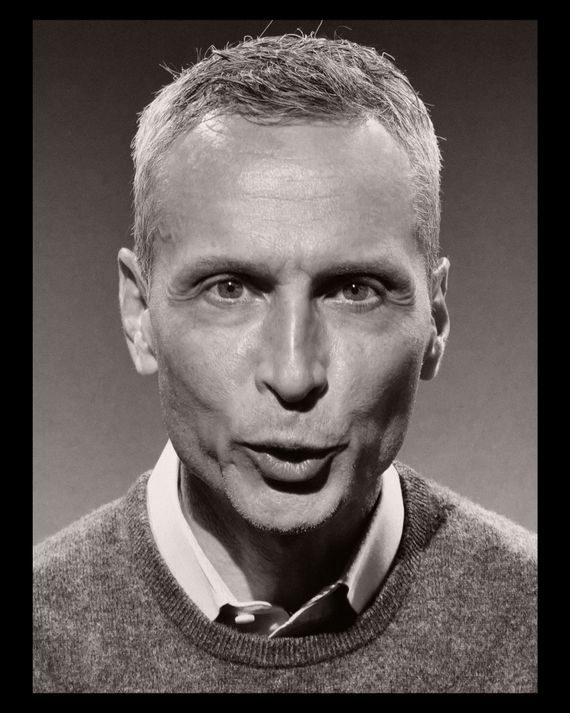

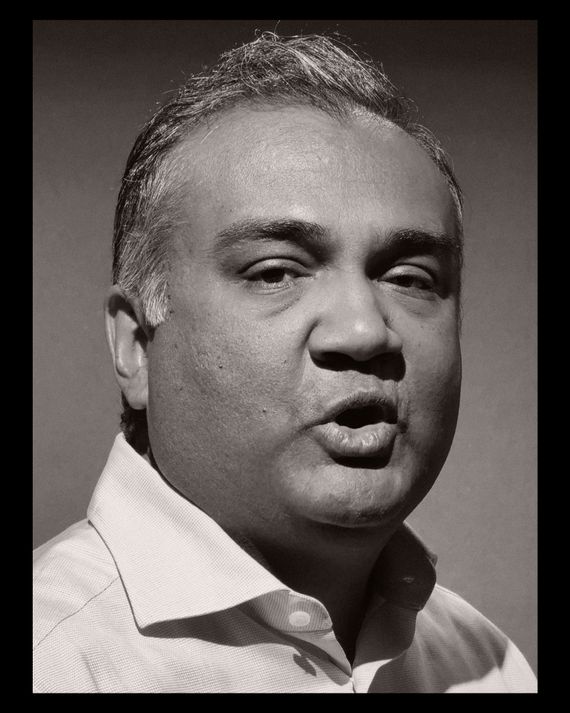

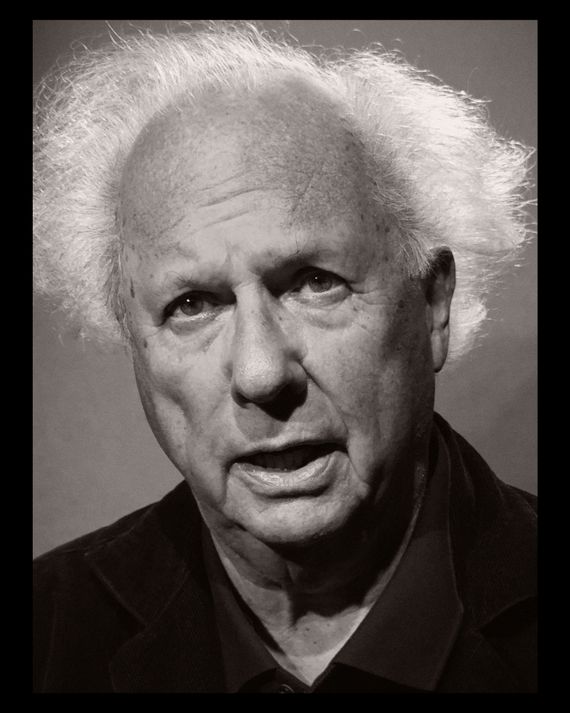

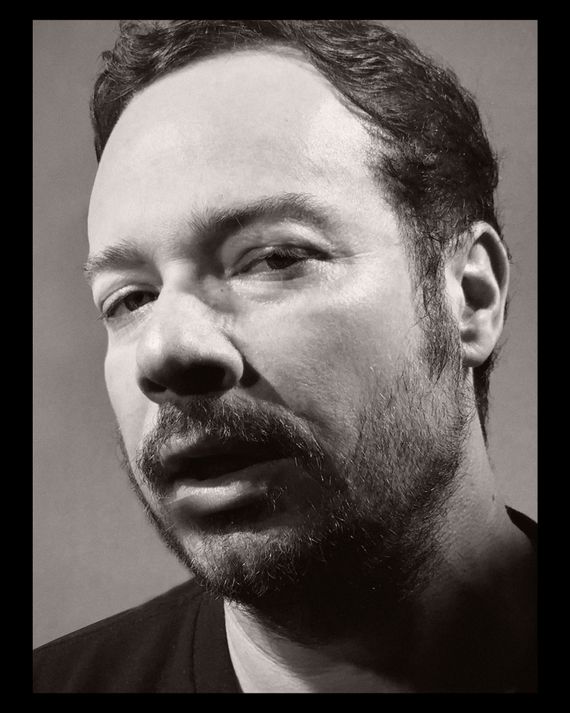

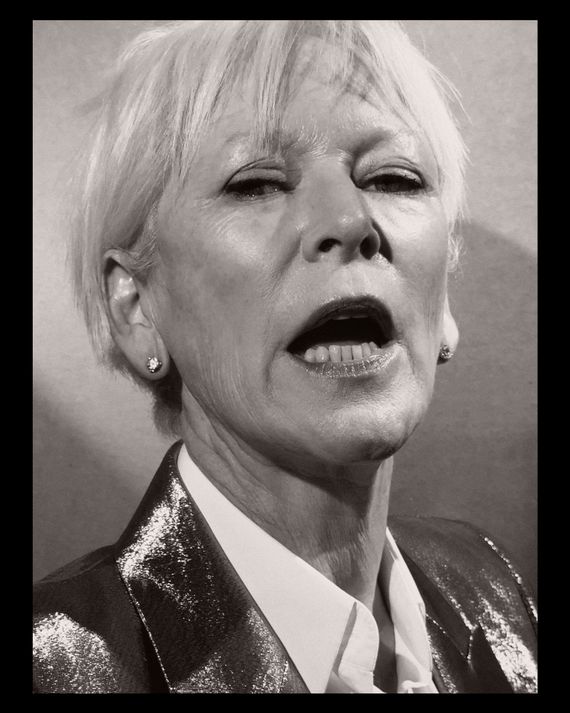

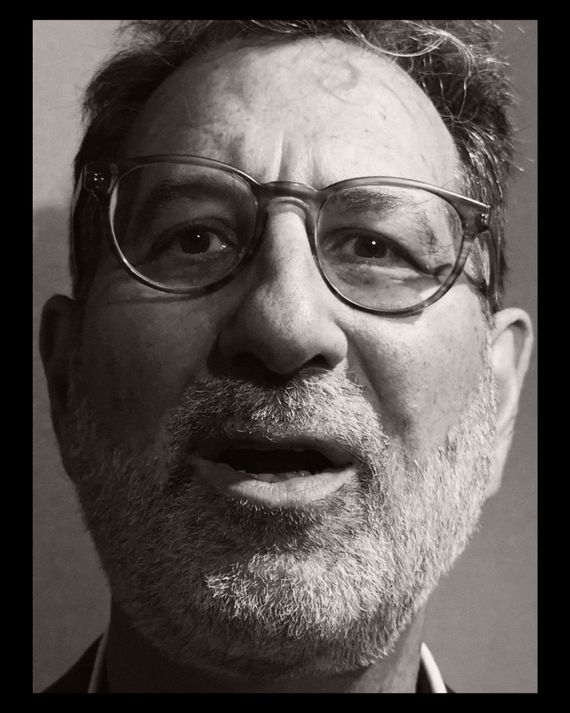

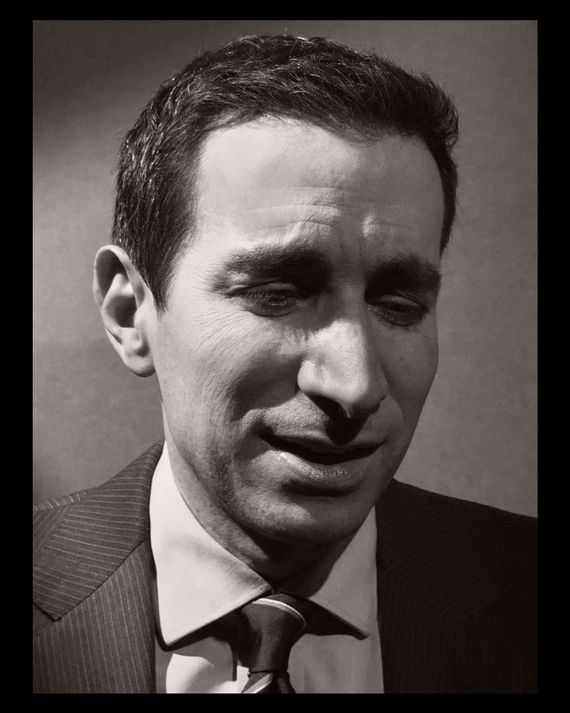

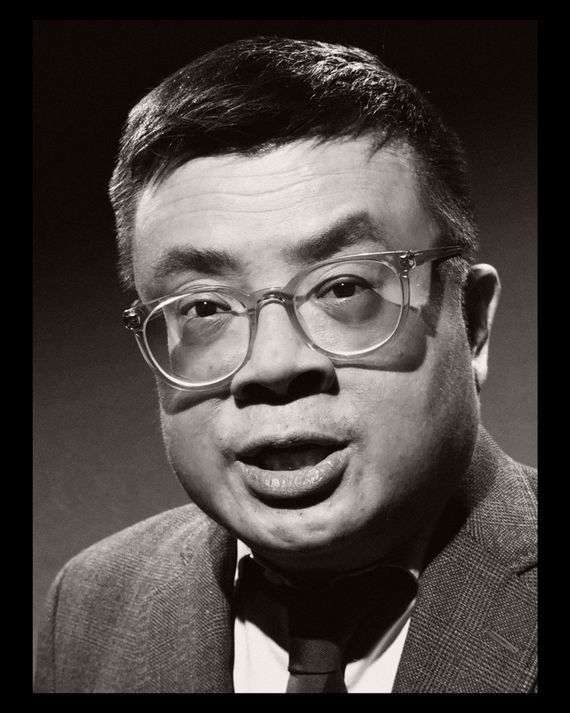

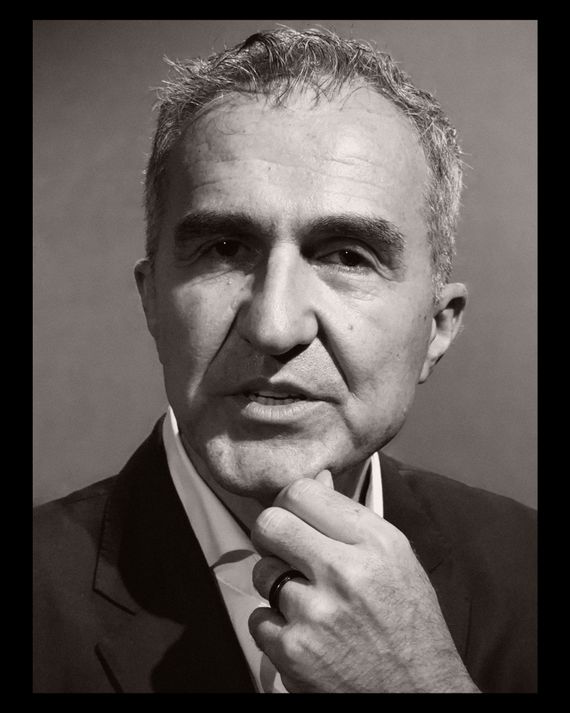

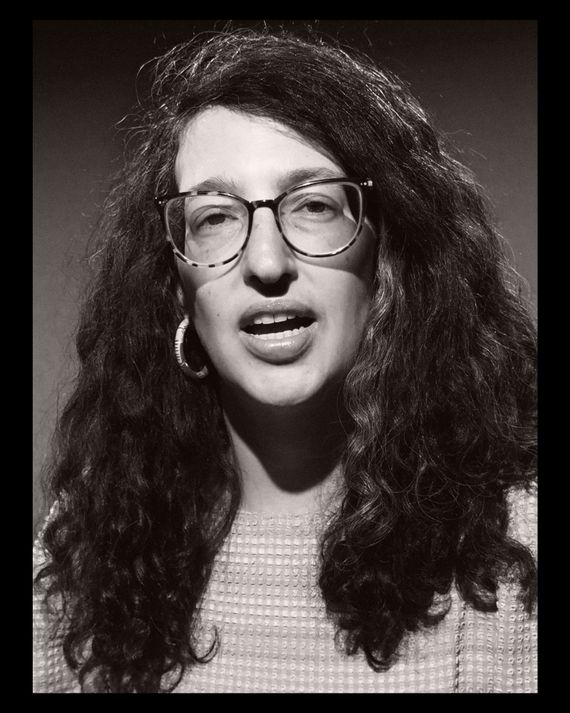

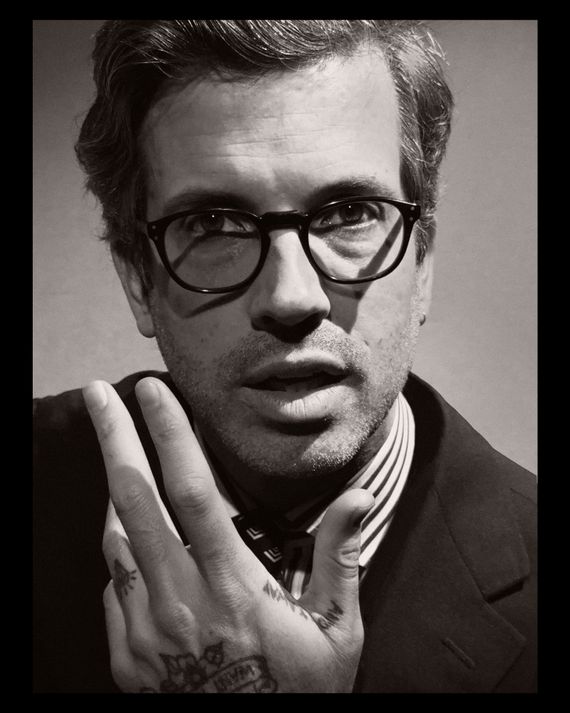

Photographed over 12 days in ten cities on the iPhone 16.

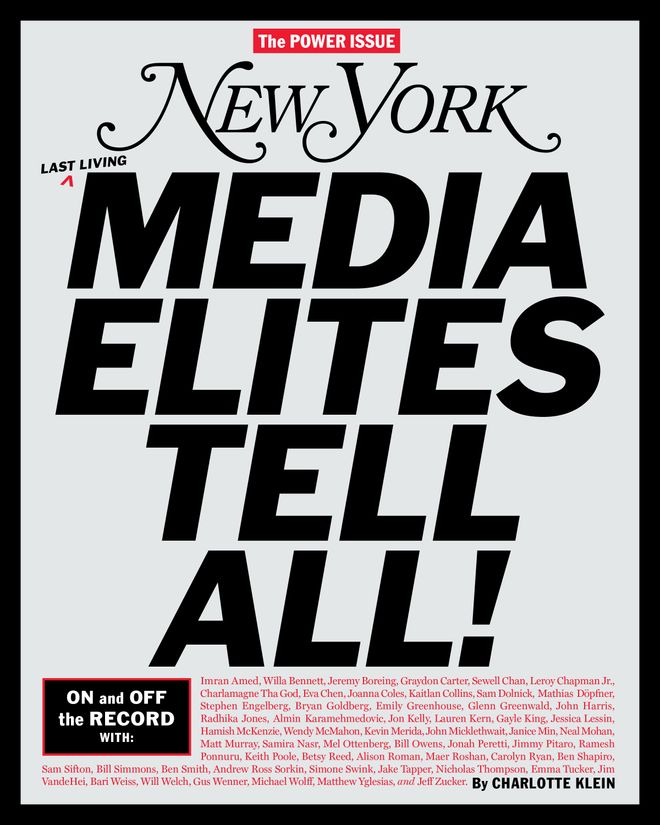

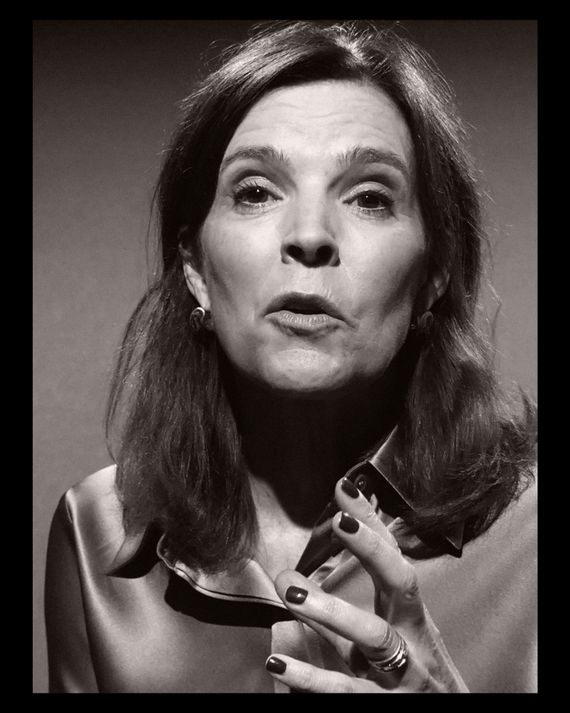

Gayle King, co-host, CBS Mornings.

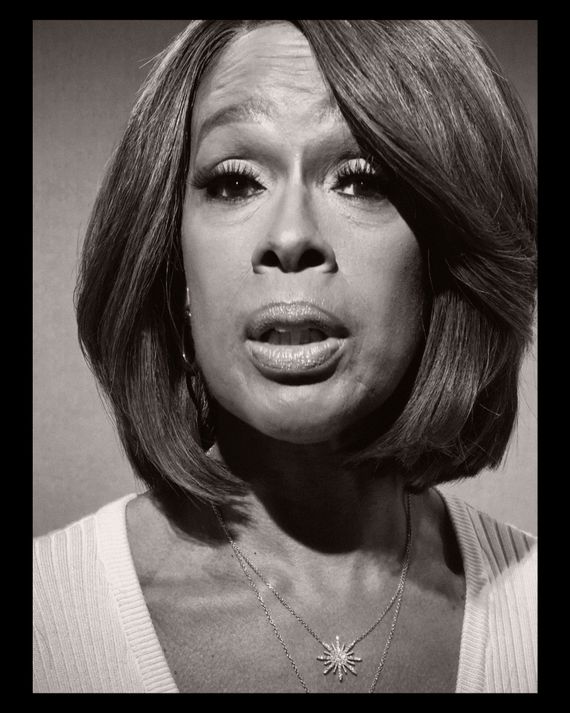

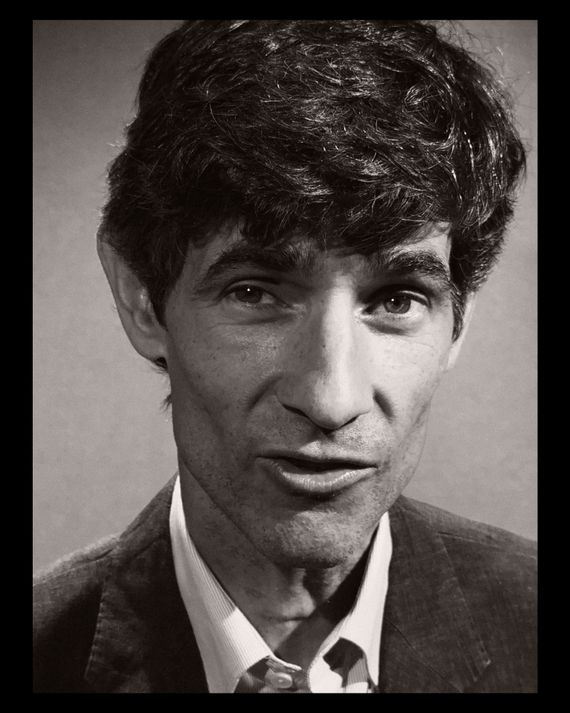

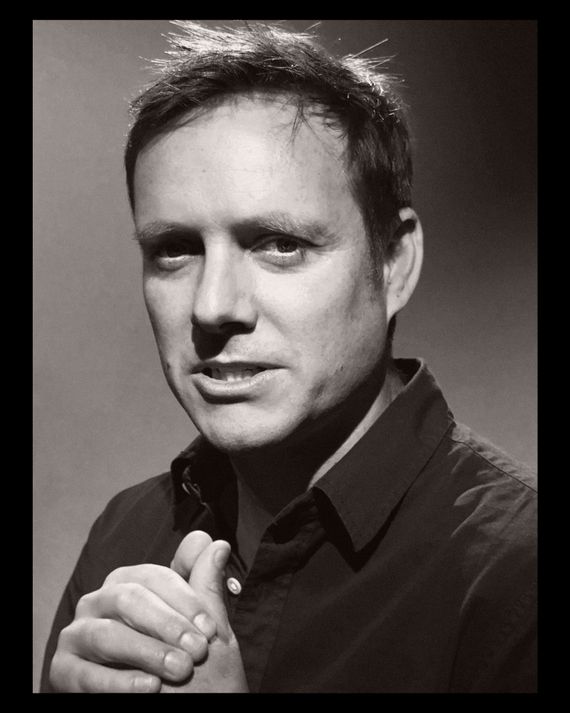

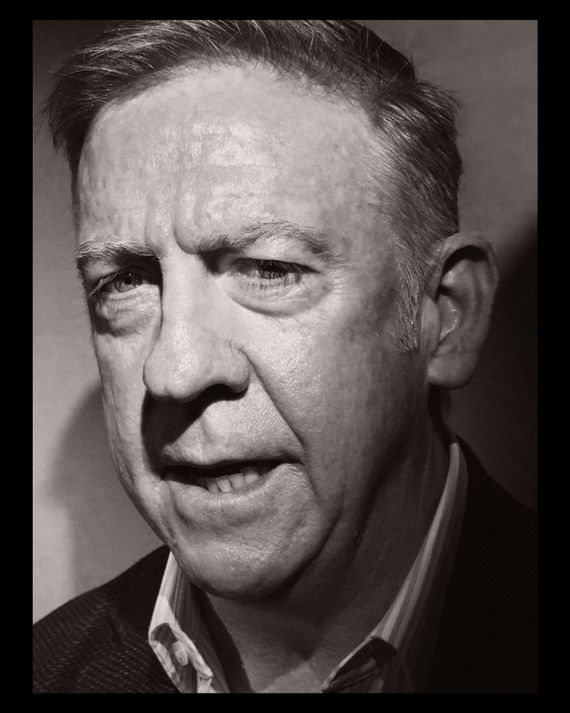

John Harris, co-founder and global editor-in-chief, Politico.

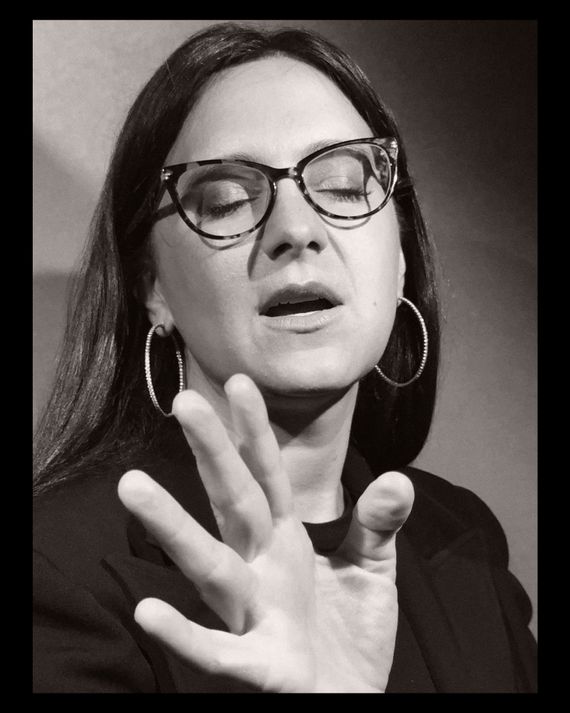

From left: Hamish McKenzie, co-founder, Substack. Imran Amed, founder and editor-in-chief, The Business of Fashion.

From left: Hamish McKenzie, co-founder, Substack. Imran Amed, founder and editor-in-chief, The Business of Fashion.

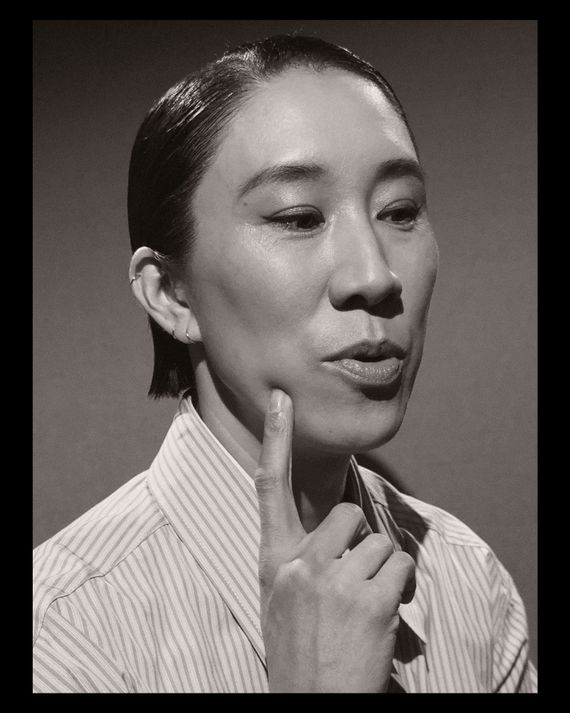

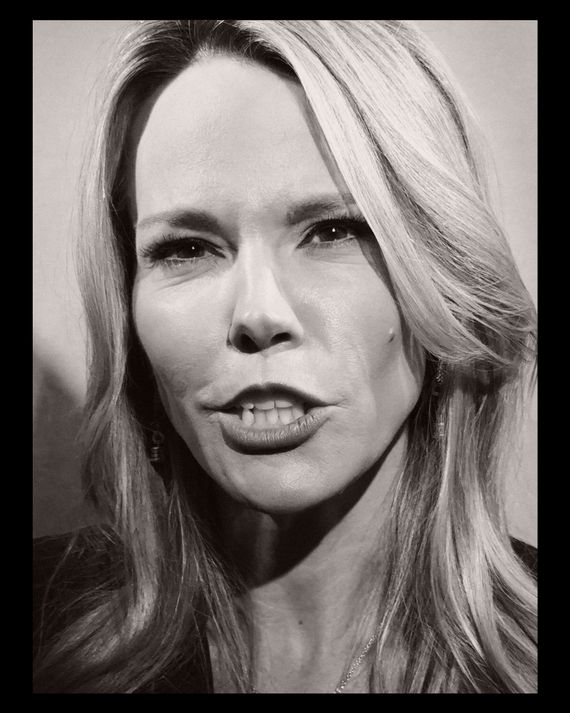

From left: Jeff Zucker, CEO, RedBird IMI. Radhika Jones, editor-in-chief, Vanity Fair.

From left: Jeff Zucker, CEO, RedBird IMI. Radhika Jones, editor-in-chief, Vanity Fair.

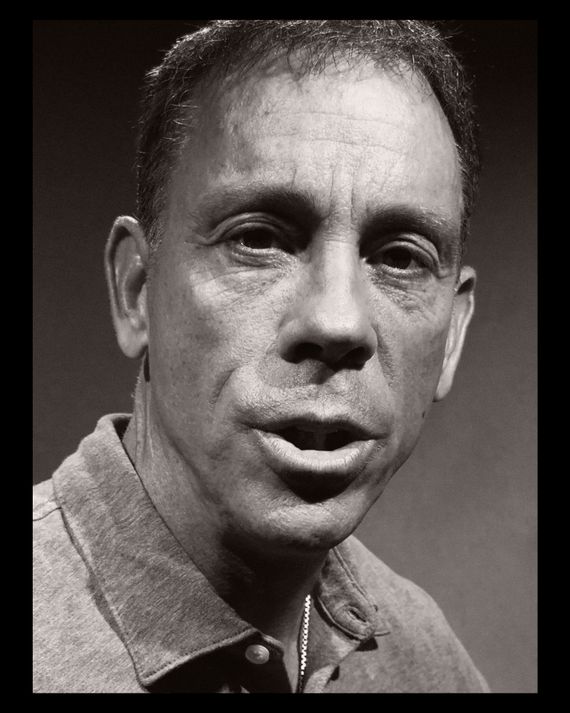

From left: Bill Owens, executive producer, CBS’s 60 Minutes. Carolyn Ryan, managing editor, the New York Times.

From left: Bill Owens, executive producer, CBS’s 60 Minutes. Carolyn Ryan, managing editor, the New York Times.

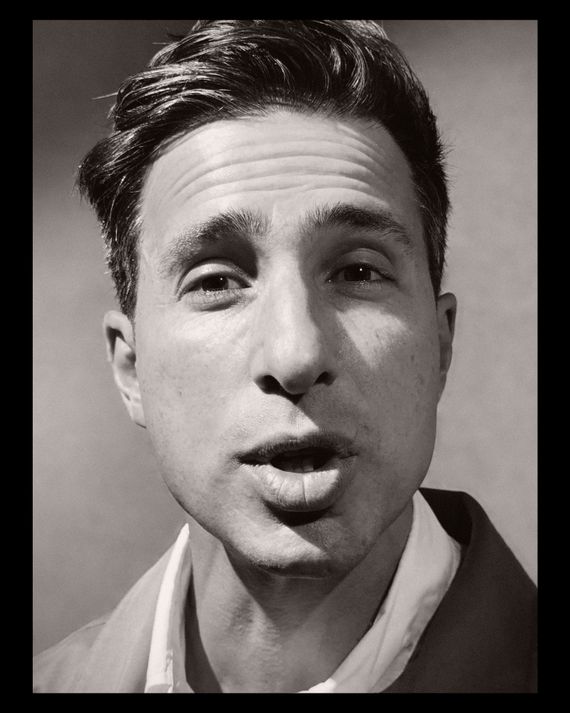

From left: Jonah Peretti, co-founder and CEO, BuzzFeed, Inc. Betsy Reed, editor, The Guardian US.

From left: Jonah Peretti, co-founder and CEO, BuzzFeed, Inc. Betsy Reed, editor, The Guardian US.

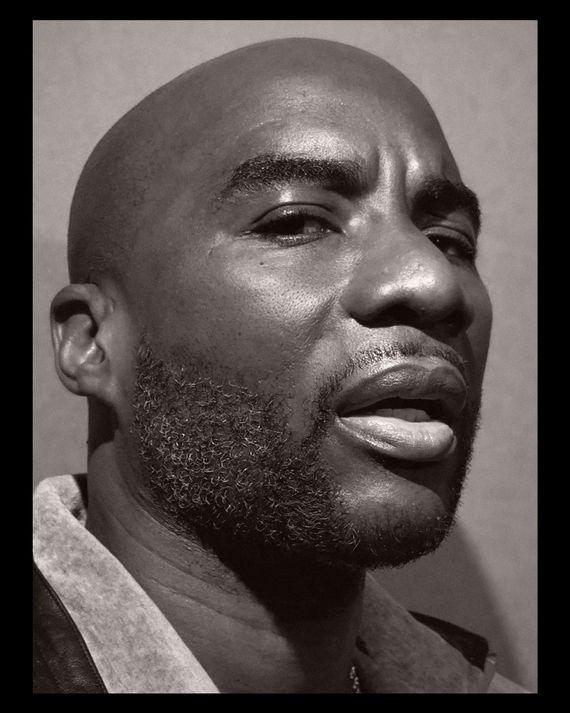

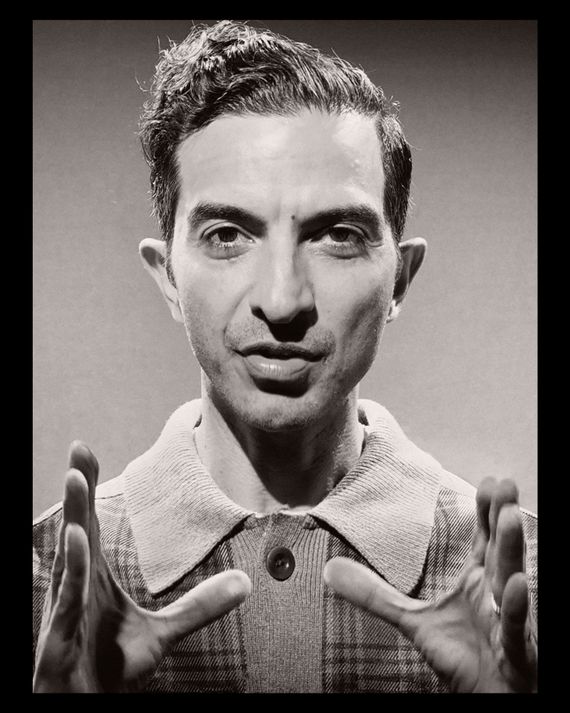

Charlamagne Tha God, co-host, The Breakfast Club.

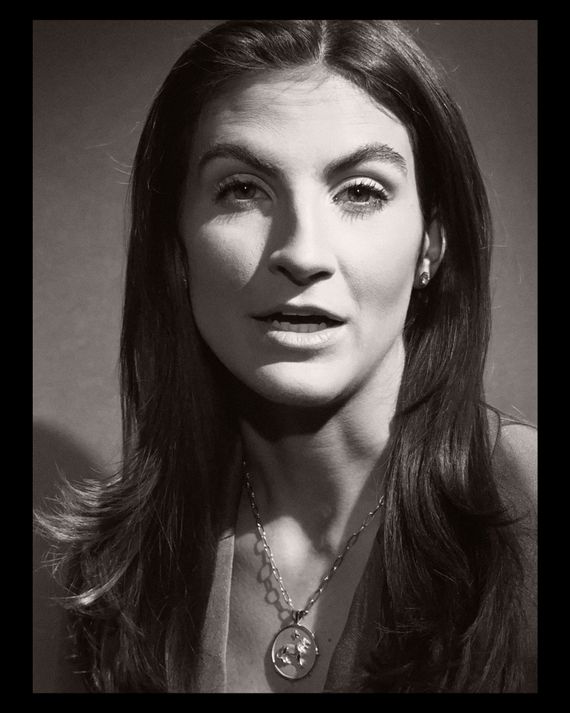

From left: Bryan Goldberg, CEO, Bustle Digital Group. Joanna Coles, chief creative and content officer, The Daily Beast.

From left: Bryan Goldberg, CEO, Bustle Digital Group. Joanna Coles, chief creative and content officer, The Daily Beast.

From left: Stephen Engelberg, editor-in-chief, ProPublica. Andrew Ross Sorkin, founder and editor-at-large, the New York Times’ DealBook; co-anchor, CNBC’s Squawk Box.

From left: Stephen Engelberg, editor-in-chief, ProPublica. Andrew Ross Sorkin, founder and editor-at-large, the New York Times’ DealBook; co-anchor, C…

From left: Stephen Engelberg, editor-in-chief, ProPublica. Andrew Ross Sorkin, founder and editor-at-large, the New York Times’ DealBook; co-anchor, CNBC’s Squawk Box.

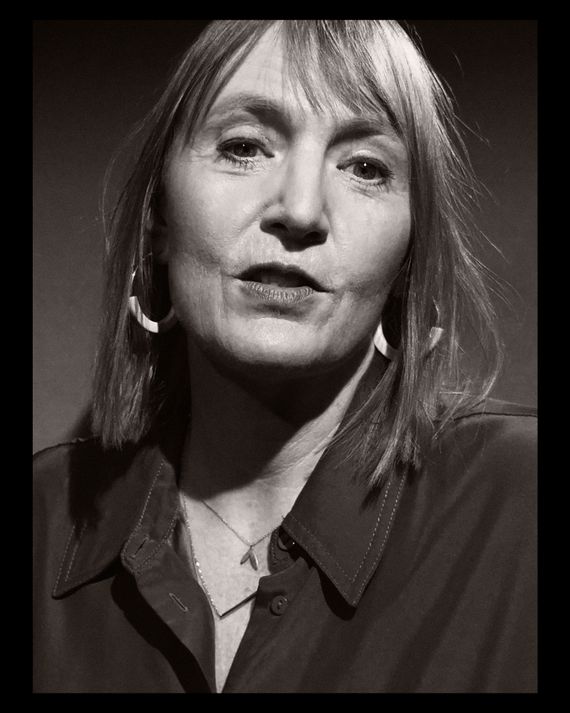

Emma Tucker, editor-in-chief, The Wall Street Journal.

Nicholas Thompson, CEO, The Atlantic.

It’s a tale of two cities. It’s almost like it’s the one percent and the 99 percent,” says a journalist surveying the field beyond the Times’ walled garden. As the rest of the industry scrambles for scraps, the Times has become the Amazon of legacy media — an everything store for blue-state America’s information needs (and more). “They’ve got Wordle and all the journalism,” says Hamish McKenzie. “Almost all the journalism talent and quality gets sucked up because it’s becoming the megalith, the giant in the room that can’t be stopped.”

“They sit on 10 million paid subs; that’s unlikely to dwindle. That’s just a very powerful base to operate from,” notes one rival editor-in-chief. “They figured it out first — how to make a killing off recipes and games that could sustain the rest of their journalism,” says former CNN boss Jeff Zucker. It’s gotten to the point that, according to one estimate, the Times now employs some 7 percent of newspaper journalists nationwide. “When other people are doing something better, they hire their people away,” says a digital media executive.

Right now, the Times is so far ahead it’s hard to imagine anybody catching up. “There’s a conversation that comes up all the time with people starting or working in journalistic enterprises, which is, ‘What’s going to be our Wordle?’” says Bari Weiss. And can anybody else do that? “Not to pick on the Times, but every answer to success can’t be, ‘Let’s point to the Times,’” says another media executive. “You’re not going to be able to replicate the Times’ success.” Just look at the new supersize app, which combines all of the paper’s many offerings. “It’s like, ‘Our newsroom of 2,000 people is just one of ten things you can be choosing,’” says an editor-in-chief.

“I envy their business model; I don’t envy their newsroom. I think it’s bloated and kind of self-indulgent,” says a top newspaper editor.

“They pivoted from being a newspaper for everyone to being a newspaper for their core reader,” says Bustle’s Bryan Goldberg. “From a purely business standpoint, that was the right decision, but I also think it made the world a much worse place, and that’s a difficult thing to reconcile.”

Some are eager to (anonymously) second-guess the Times’ business decisions, too. “They’ve been terrible with podcasts for the most part,” says one media executive. “They spent $550 million on The Athletic when they could have just spent $100 million and gotten all the best sportswriters. It’s like, Oh, you guys don’t know what you’re doing.”

But a lot of that just feels like sour grapes. “It’s amazing to me that they’re the piñata of American journalism,” says Stephen Engelberg. “Whatever they write, somebody’s constantly whacking. They do more good stories in a week than many of us do in months. And you have to tip your hat to people who can get inside the Supreme Court in real time. That’s really something.”

“Part of the problem in the media business has been the collapse of brands, and the Times has managed to maintain its,” says Michael Wolff. For a journalistic buccaneer like Wolff, the operations of that brand machinery feel soul-crushing. “You want to work at the Times? I’d rather kill myself.” The feeling is likely mutual.

One of the most lauded legacy enterprises that is not the Times is The Wall Street Journal — and most of the credit goes to its editor, Emma Tucker, who arrived early last year and was immediately confronted with Russia’s arrest of reporter Evan Gershkovich. She also had to get up to speed on covering a presidential election in a country that isn’t hers while remaking a somewhat bloated and stultified newsroom into one closer to the lighter-on-its-feet U.K. model. And she somehow did it. “I think that they’ve passed the Washington Post,” observes one veteran journalist.

Her makeover of the paper into a livelier, more audience-conscious read has been widely praised. “I rarely considered The Wall Street Journal near the top of my ‘fun read’ list in the past,” says Timesman and CNBC co-anchor Andrew Ross Sorkin, but it’s become “a lot more interesting and readable. I think every day I find more features that are accessible and surprising. I feel the heat of what they’re doing. I feel it in the headlines.” New York Post editor-in-chief and fellow Rupert Murdoch employee Keith Poole enthuses, “She’s brought a way of telling a story from the headline down that’s much more instantly engaging and a much faster drumbeat of scoops.”

From Elon Musk exposés to being early on Joe Biden’s cognitive decline, “she’s pissed off a lot of people along the way, but it’s a more interesting and surprising read now,” notes another editor. She had several advantages coming in, though: The Journal was early to having a paywall, which its business readers were willing to pay for (and expense). Since Murdoch bought it in 2007, it has become the national center-right quality newspaper. Which means people who can’t abide the Times can instead get the Journal. The L.A. Times and the Washington Post, meanwhile, have arguably been fighting for the same educated, blue-bubble reader.

And in the end, Tucker also got Gershkovich released.

Who else is having a good year?

2Way

“I was at a dinner party and was told that someone well known was told the only person you have to read to understand what’s happening right now is Mark Halperin. So I immediately log on to 2Way and I’m like, Wow, it’s like $5,000 or $3,000. He does these nightly Zoom calls, which are like live cable television but with audiences that he’s curating. I was just sitting at home watching CNN at my parents’ house and thought, Why am I doing this? I should’ve been dialing into his Zoom and hearing from him and all these experts whom he’s bringing to the table about whether Biden was going to step aside. It was awesome. Nancy Pelosi’s former chief of staff was one of the speakers, then he went to Jill Abramson … I’ve been kind of blown away by this, honestly, because it feels like something really new and really authoritative.” — Jessica Lessin

The NBA

“No one is having a better year than the NBA right now. They’ve just completed a historic negotiation that makes their media rights almost as valuable as the National Football League’s own media package. And they have an incredible business model with proven, engaged owners, and they — the owners and Adam Silver — have done an excellent job of convincing the three or so biggest entertainment companies that their sport is vital to long-term survival in the industry.” — Jon Kelly

The Ringer

“It seems to be having a lot of fun, and they’re trying a lot of stuff. It feels like they’ve got momentum.” — Sam Dolnick

Ezra Klein and Bari Weiss

“The stars of 2024. This is their year.” — Matthew Yglesias

The Daily Wire

“I think the way they’ve been able to leverage cultural commentary and expand beyond the traditional audience that consumes political content — that’s pretty enviable.” — Glenn Greenwald

Barstool Sports

“I mean, look, it’s so far afield from the way I approach the world, but they totally have figured out how to capture the attention of a particular cohort and generation of people.” — A top journalist

Call Her Daddy

“What Alex Cooper’s building with her company — whenever you’re able to take one platform, which is the Call Her Daddy podcast, and turn that into a network that has other podcasts on there that are just as big — you have to salute that.” — Charlamagne Tha God

“The group chats, the private texts, voice memos. Don’t ever put anything in writing.” — Alison Roman • “I think I would say from the source.” — Michael Wolff • “Sometimes my colleagues and partners, but I have about three or four people I talk to almost every day.” — Jon Kelly • “The parties I host.” — A media executive • “Well, I get a lot of my gossip from Ben Shapiro.” — Jeremy Boreing • “The New York Post.” — Gus Wenner • “I feel like the D.C. bureau of the New York Times has better gossip than the one in New York. Always. Anybody who’s not in the main office knows more than the people there or has gossip about it. They’re all trying to figure out what’s happening all the time.” — A top journalist • “Group chats. Word of mouth on the street. Instagram.” — Mel Ottenberg • “I read our staff Slack channels, so I’m vicariously reading Lainey Gossip and the Daily Mail. Then obviously I have group chats, and most of those are on Signal.” — Radhika Jones • “Cocktail parties, of course.” — Ramesh Ponnuru

Substack launched in 2017, offering journalists tired of giving all their insights away for free on what was then known as Twitter (or of trying to entice readers to their paywalled blog) a plug-and-play service to launch email newsletters people could pay to subscribe to. And now even Tina Brown has signed on.

But the email pile-in goes beyond the solo proprietors, whether zoomer or boomer. With the decline of social media in general as a way to distribute news, even the legacy news operations got in the game, launching specialized newsletters hoping to drive traffic back to their paywalled websites or as a sort of concierge content-delivery service for their subscribers interested in a particular topic or writer. “I’m bullish because it’s relatively low cost and easy to do, and a great voice is all you really need,” says the Times’ Sam Dolnick. “It’s a direct relationship between the writer and reader.”

But for a newsletter to work, it has to give that reader something they think they need — intellectual companionship or insight or entertainment. Ben Shapiro calls such products “textual extensions of a podcast.”

“Somebody like Nate Cohn, who is our polling expert — you can read a newsletter that might be just 800 words and come away feeling smarter,” as Carolyn Ryan puts it.

Email isn’t glamorous. “I hate the name, and somebody’s going to have to come up with something sexier. The term newsletter sounds like something that comes out of a church basement,” says Graydon Carter, whose publication, Air Mail, has brought more magazine glamour to emails than any of its peers. “But the brilliant thing about it is it’s free home delivery, and there’s no printing or shipping. If this sort of technology had existed, nobody would ever have invented a magazine or a newspaper.” Everybody gets email and opens at least some of it. “I think the most moronic thing I’ve ever heard, in terms of conventional wisdom in media, was that we reached peak newsletters,” says Axios’ Jim VandeHei.

In some ways, the Substack career track has taken the place of the dream of the low-overhead, self-sustaining blog. As Substack’s Hamish McKenzie attests, it means writers “being able to make money directly from the readers instead of hoping that they’ll amass some kind of audience from which will trickle down some advertising dollars or some brand deals or something like that.”

There’s no question it works for some people. “I know a lot of writers who have been able to leave their media jobs because they can have a Substack and do really, really, really well, and sometimes they make more money,” says Willa Bennett of Seventeen and Cosmopolitan.

But most people don’t have enough of a preexisting following to make a living off it.

“It’s great for Casey Newton, but there’s not that many people it’s great for,” says one media executive. “My understanding of it is that 5 percent of the writers are making 90 percent of the money, which I don’t find surprising,” says The Daily Beast’s Joanna Coles. Beyond subscriptions, that money includes sponsorships, ads, the works — like a mini-magazine.

And then there is the issue of quality control. “Some of them are fantastic, and some of them could really use editors and infrastructure,” notes one top editor. “And the trouble with platforms that are distributing them is that there’s not that kind of editorial infrastructure to vet, to push back, to say, ‘Wait a minute — is that actually a story?’ or ‘Is that headline fair?’ There just aren’t enough people to be the checks and balances. So in some ways, it’s much more similar to social media.”

“I pay for Emily Sundberg’s and I pay for Rachel Karten’s.” — Alison Roman • “I pay for Drop Site News, which is the Substack started by my old colleagues from The Intercept. I pay for Zeteo, and I pay for Slow Boring.” — Betsy Reed • “I subscribe to Hunter Harris, Notes From Auntie’s Desk, Emilia Petrarca, Leandra Medine, Amy Odell, and a few others.” — Eva Chen • “John Ellis, Andrew Sullivan, Tina Brown, Joe Klein, Judd Legum, Roger Pielke Jr.” — Matt Murray • “I pay for Nate Silver, Noah Smith, Cartoons Hate Her, Tim Lee.” — Matthew Yglesias • “I pay for Ben Thompson’s newsletter.” — Nicholas Thompson • “I don’t pay for Opulent Tips, but it’s absolutely my favorite. Emily Sundberg. Casey Lewis. Amy Odell. Emilia Petrarca.” — Willa Bennett • “I pay for Andy Borowitz. And The Free Press.” — Graydon Carter • “Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Steve Schmidt.” — Gayle King • “I appear to be paying for probably 30 or 40 different Substacks, which I can’t figure out how to not pay for.” — Joanna Coles

Nearly all the people interviewed for this project read at least one of the view-from-inside-a-particular-industry newsletters (from Hollywood to fashion to the art market) that make up the subcription-based Puck. “They have a lot of swagger. They have been successful in creating buzz. I know people who despise them. I’m meeting a lot of executives and studios and other places who don’t like them, but they consume them. They’re a little sloppy, too, and I wonder how much there is there,” says one media executive. Four more perspectives from four more media executives:

1. It’s Chatty.

“I’m surprised by how much I read Puck. They’ve broken news, but that whole newsletter style — maybe that’s the future of what writing’s going to be now, a little conversational.”

2. It’s Gossipy.

“I think they know their audience and are doing work that you don’t find elsewhere. But it’s really just for wicked little gossip. And I think that most people are gossips, or at least most people in our industry. So to have somebody who’s just like, ‘Here’s some shit to talk about somebody,’ it’s kind of fun. And I think that’s a thing I could see building a business around. That’s not the kind of journalism that I get most excited about or aspire to, but I think that there’s a lane for that.”

3. It’s Maybe Too Much Fun to Be True.

“I believe most of their reporting. I mean, in some ways, they’ve gotten things massively wrong that involve me, so maybe I shouldn’t put that there.”

4. And Private-Equity Financed.

“They have taken on a lot of money, and I think it’s a little bit replicating the model of the previous decade. You’re just trying to outrun the money, but it eventually catches up.”

At a moment with no shortage of content, breaking news is what sets publications, especially the upstarts, apart.

“The biggest message is to get scoops. I just think that the talent dynamics in the industry are changing so fast, and that the value of doing pretty good work goes down every day, and that you need to either play a really essential supporting role or really break out, and there’s less and less space between those two things,” says Semafor’s Ben Smith.

“It is a great time to be in the excellent-journalism business, and it’s a shitty time to be in the mediocre-journalism business. I think there is a great business in hit-driven journalism — the biggest scoop, the biggest investigative story, maybe the top 20 percent of what great journalists and news organizations are doing,” says The Information’s Jessica Lessin. “The reality — and it’s not an easy reality to contend with — is there’s not a great business for the 80 percent.”

“I said to everyone here after a kind of mediocre pitch meeting: ‘Just to remind everyone, this right here is the business,’” says Bari Weiss of The Free Press. “‘There’s not another secret business. The business is the stories that you pitch and the scoops that you bring to me, and if they’re not good, the business will not grow.’”

But scoops don’t live very long anymore.

“We’re in this age when news breaks — which are the great bragging rights of any journalist — are so ephemeral,” says Janice Min. “They disappear almost instantly because everyone else jumps in and has a hot take.”

The decadelong effort to diversify historically white and male newsrooms seems to have slowed. While some participants reaffirmed the idea behind DEI — “If your ambition is to really cover the world as it really is,” says Times assistant managing editor Sam Sifton, “then you need to have a newsroom that looks like the world outside” — there was a broad sense that the focus has shifted. “No one cares about diversity,” notes a (non-white) executive. “No one’s going to be like, Oh my God, another white guy getting the job. I think we took two steps forward, one step back.”

One executive says, “I think being performative about it is less of a thing now than it was two years ago, and thank God.” Instead, as a (white) executive puts it, those being hired are candidates who “are qualified for these jobs rather than just because they are not a white male.”

But one downside of DEI was that not everyone brought in under its impetus felt supported. One (white) editor says, “I have a lot of friends, especially some Black people in publishing who I am close with, who feel that there was a real tokenization. I have a friend who’s a literary agent who was brought into a large talent house and just left to start her own boutique thing. She was really being called on to bring in a certain kind of perspective — the ‘diverse thing.’ And that’s not really what her focus is.”

Entry-level journalists “are not nearly as talented as the people ten and 15 and 20 years ago,” insists one newspaper vet. There are lots of reasons that may be the case. “It used to be that you would give someone the advice, ‘Go work for a small-town paper and then come to me,’” says Bari Weiss. “Well, they’re all gone.”

Combine that with the pandemic and the rise of WFH and you get young staffers who never had a chance to be mentored. “They’re probably maybe a little less qualified because they’re less trained; the whole attitude is less servile than it used to be,” notes an editor. “You have people who are — I don’t want to say working fewer hours, but the mode of dues paying has changed a lot.”

One executive expressed frustration with Gen Z this way: “They want everything right away. They want everything fast. They’re super-ambitious in the wrong ways. The people that seem to me to succeed are the ones that just do good work, really push themselves, and assume the right people are going to notice. And guess what? The right people always notice. The stuff you never want to deal with is somebody who’s been there for nine months already asking what your long-term, seven-year plan is. It’s like, ‘You just got here. I don’t have a plan for you yet.’” Another editor-in-chief carps, “My biggest pet peeve is when it feels like I’m the teacher and they’re in sixth grade doing a homework assignment.”

Perhaps unsurprisingly for a group of owners and managers, the rise of media unions over the past decade was treated mostly as a nuisance.

“I’ve always been supportive of unions, but I think the unions today are different and the guilds today are different,” says one executive. “They more mirror the activists’ posture on social issues and everything else.” The New York Times, as usual the industry bellwether, has clamped down on employee dissent under executive editor Joe Kahn after a staff revolt forced the ouster of “Opinion” editor James Bennet in 2020. A top newspaper editor says, “You have to know where to draw the line in a news organization between activism and professionalism. Kahn has finally drawn a line with that, and good for him.” Other organizations have struggled with the same issue. “You see what happened at the Washington Post; essentially, it’s anarchy,” says an anonymous executive. “The staff took over the publication and started dictating moves.”

Outside the activist front, some felt unions hadn’t delivered to their members. Nearly everyone recognized that management’s relationship to staff has probably changed permanently, at least compared with when interns were forced to work for free and assistants were expected to dog-sit for their bosses on weekends and worse. “You could just make people do whatever, whenever,” says Janice Min of the go-get-me-a-salad days of magazine editors pushing around their underlings. “Now, there’s just a much greater sense of boundary.” Still, there was some nostalgia for a time when a boss could push their charges to the limit. “I’m not saying you have to come to the office, but the people who do the best work — all of them — work really hard all the time. And you can’t say that anymore,” says an executive.

As with DEI, there is a sense, at least among managers, that, in the face of larger disruptions, the media labor revolution has gone as far as it is going to go. Starting wages have been raised, severance deals were better formalized, rules were negotiated as to what happens to the TV or film rights to an employee’s articles. But many executives suggest you can squeeze only so much out of a barely profitable business.

“Between the years, like, 2016 and 2021, the relationship between employers and employees shifted, and it’s shifted back, basically,” says one editor-in-chief. “That was a temporary phenomenon that really strikes me as over.”

“Journalism with a capital J is no good to anyone if nobody’s reading it.” — Emma Tucker • “The newsroom has to understand that it needs to align itself with the wider business goals. It can’t operate in isolation. We’re in such a fight for everyone’s time, and with paid subscription, we’re also in a fight for their money. Every editor is probably thinking, when they’re assigning something now, What is the ROI on this?” — Janice Min • “You want to write about Hamas in Israel? No one’s going to advertise against that. If you write a story about a female entrepreneur who’s made it up from poverty, I can sell infinite ads.” — Top editor No. 1 • “Thousands of people would kill for these jobs.” — Top editor No. 2 • “This job is really, really hard, and you don’t do it by sitting at a desk text-messaging.” — Top editor No. 3 • “Could be worse. You could be in academia.” — No. 4 • “It’s a hard job and it takes a lot of hours and you don’t always get clapped on the back and not everybody gets a sticker.” — No. 5

In the year since October 7, leaders of news organizations have had to defend their coverage, not only to the readers, but also to their staff.

“I worried constantly last fall over alienating our contributors, our readers, and especially our colleagues. The past year has helped me learn and defend the position that we don’t all stand at exactly the same place on the left, and it’s perfectly healthy to follow the voices of our writers and help them to best articulate their beliefs. I also feel proud — I’m not joking when I say this — that no one has quit because of what we’ve done.” — Emily Greenhouse

“The most divisive issue internally in the last decade, more so than George Floyd.” — A digital media executive

“I have never experienced anything as intense as that moment, and I’ve been leading newsrooms for a long time. The depth and intensity of emotion, and the microscopic scrutiny of every word and every headline, is like nothing I’ve been through.” — A top editor

“Breaking through the individual personal circumstances that people are feeling and the framing and different degrees of activism people bring to the most fraught subject in the world — and finding a way to talk to people directly about those things in an honest way that makes clear your expectations without them feeling challenged, threatened, or that you have an agenda to drive — it’s very hard.” — An editor-in-chief

“This story is a different level. There’s no question about it. I think you have to be extra careful in the words you use and the way you tell the story.” — Gayle King

“It’s really, really difficult to cover a war when you only have access to one side. And so the lack of on-the-ground reporting from Gaza is really, really a handicap.” — Stephen Engelberg

“Every subject became politicized. Everything from our fashion coverage to our art coverage to our restaurant coverage became proxy for that war.” — A top editor

“I’m going to skip that one.” — An editor-in-chief

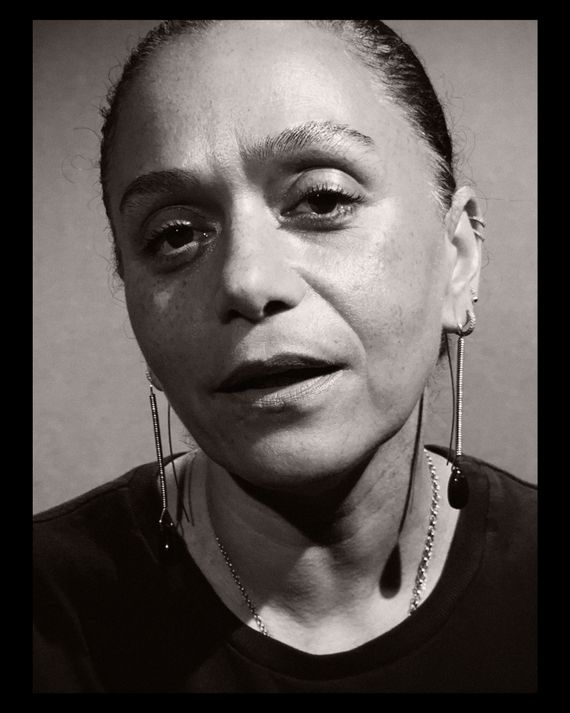

From left: Michael Wolff, author. Kevin Merida, former executive editor, the Los Angeles Times.

From left: Michael Wolff, author. Kevin Merida, former executive editor, the Los Angeles Times.

From left: Sam Sifton, assistant managing editor, the New York Times; founding editor, New York Times Cooking. Mathias Döpfner, CEO, Axel Springer SE.

From left: Sam Sifton, assistant managing editor, the New York Times; founding editor, New York Times Cooking. Mathias Döpfner, CEO, Axel Springer SE….

From left: Sam Sifton, assistant managing editor, the New York Times; founding editor, New York Times Cooking. Mathias Döpfner, CEO, Axel Springer SE.

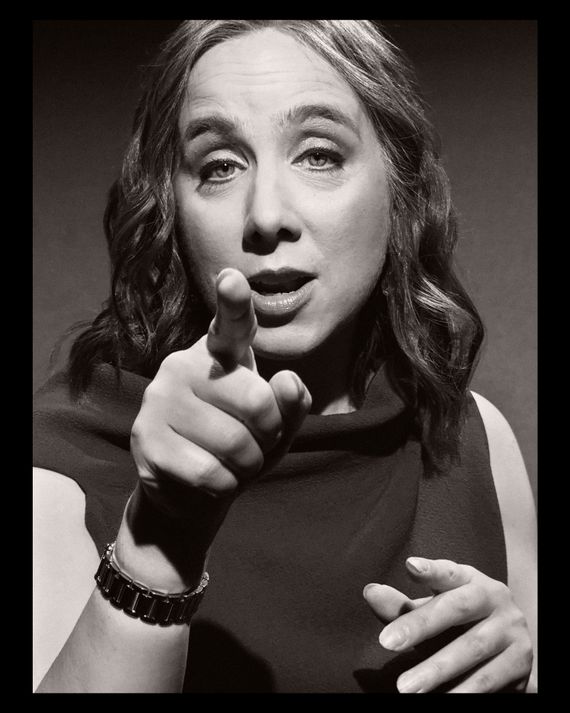

Bari Weiss, founder and editor, The Free Press.

From left: Ramesh Ponnuru, editor, National Review. Maer Roshan, co-editor-in-chief, The Hollywood Reporter.

From left: Ramesh Ponnuru, editor, National Review. Maer Roshan, co-editor-in-chief, The Hollywood Reporter.

From left: Keith Poole, editor-in-chief, the New York Post Group. Jessica Lessin, founder and editor-in-chief, The Information.

From left: Keith Poole, editor-in-chief, the New York Post Group. Jessica Lessin, founder and editor-in-chief, The Information.

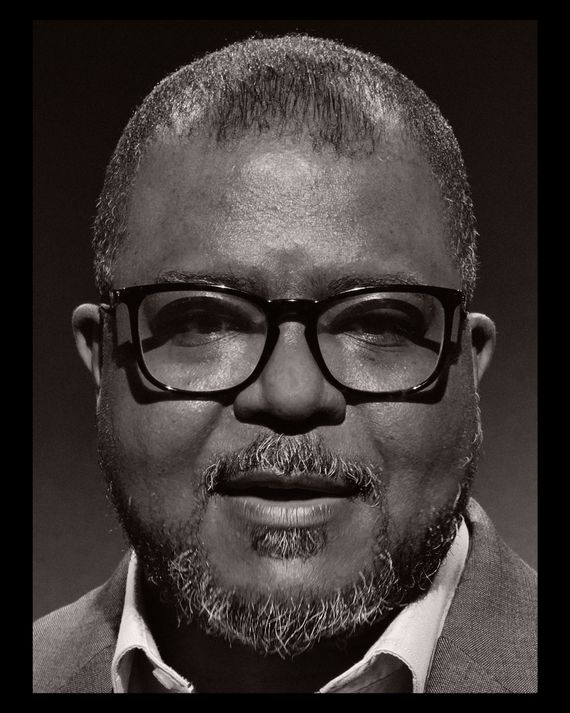

From left: Leroy Chapman Jr., editor-in-chief, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. John Micklethwait, editor-in-chief, Bloomberg.

From left: Leroy Chapman Jr., editor-in-chief, the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. John Micklethwait, editor-in-chief, Bloomberg.

From left: Jake Tapper, anchor and chief Washington correspondent, CNN. Lauren Kern, editor-in-chief, Apple News.

From left: Jake Tapper, anchor and chief Washington correspondent, CNN. Lauren Kern, editor-in-chief, Apple News.

Eva Chen, vice-president of fashion, Meta.

Jimmy Pitaro, chairman, ESPN.

From left: Gus Wenner, CEO, Rolling Stone. Sewell Chan, executive editor, Columbia Journalism Review.

From left: Gus Wenner, CEO, Rolling Stone. Sewell Chan, executive editor, Columbia Journalism Review.

From left: Almin Karamehmedovic, president, ABC News. Emily Greenhouse, editor, The New York Review of Books.

From left: Almin Karamehmedovic, president, ABC News. Emily Greenhouse, editor, The New York Review of Books.

From left: Janice Min, founder and CEO, Ankler Medi. Will Welch, global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork.

From left: Janice Min, founder and CEO, Ankler Medi. Will Welch, global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork.

From left: Glenn Greenwald, host, System Update; co-founder, The Intercept. Matthew Yglesias, writer, Slow Boring; co-founder, Vox.com.

From left: Glenn Greenwald, host, System Update; co-founder, The Intercept. Matthew Yglesias, writer, Slow Boring; co-founder, Vox.com.

Throughout the 2010s, the media business was a minter of great fortunes, and its proprietors — Rupert Murdoch, Barry Diller, Si Newhouse, etc. — were powerful, influential, and rich in the model of Citizen Kane. In the subsequent tumult of managed media decline, nobody has really replaced them. “It doesn’t feel like there are the kind of individuals wielding huge power in the way that they once seemed to loom over not just the industry but the culture,” says a top editor. “It feels like the older 70s-and-up crowd is kind of heading toward being done soon, but nobody really knows who the 50s and 60s people are,” says one media exec. People of that generation who made a play for it, like Jonah Peretti and Vice’s Shane Smith, have been humbled.

It’s not that there aren’t moguls. It’s just that they have less swag. “Technically, in terms of the reach of assets, I mean, it would be the Roberts family,” which owns Comcast, “or [Warner Bros. Discovery CEO David] Zaslav, I suppose, just by holding more assets and by holding a larger audience,” says Michael Wolff. “But there’s no resemblance to the executives who once ran this business.” “Graydon Carter, Lorne Michaels — you knew who all of them were,” says a media executive. “Richard Plepler. And they were all friends, and they all felt like they were running New York in a lot of ways. And I don’t know who that is anymore.”

Yes: “The source of his power is Fox News, The Wall Street Journal, and the New York Post. It’s just an unbeatable combination that those three properties have a stranglehold on conservative thought in America.” — Jeff Zucker

No: “Well, that’s completely idiotic. Just showing the fact that nobody knows shit about what is going on in this business. First thing, Murdoch is 93 years old and barely sentient. Secondly, much of the empire that Murdoch had, hello, was sold off in 2018, which somehow people don’t quite focus on. He continues to have Fox News, which continues to be a significant voice in American politics, of course. But it is a less significant voice than it once was and will continue to be ever lesser — No. 1, because it’s in the cable-television business, which is in fast decline, and No. 2, because there actually are now real-time meaningful competitors in the conservative media space anyway. On top of which, what is left of the Empire is under enormous, enormous internal stress.” — Michael Wolff

“He’s the richest man in the world, who controls this massive platform that has a huge impact on what information and what media sources people are exposed to. And he has however hundreds of millions of followers himself, and he is actively and openly campaigning for Trump to be elected president. The degree of his power, it’s just mind-boggling and not in a good way.” — Betsy Reed

“He has a massive platform, and he exploits the shit out of it.” — Jim VandeHei

“The source of his power is his willingness to use it at the expense of his business to move politics in the short term.” — Ben Smith

“In 2016, if Rupert Murdoch had advocated for a VP candidate to Donald Trump, that person probably would’ve become the VP. He did that this time with Doug Burgum, and Trump didn’t pick Burgum. Ultimately, he was listening much more to the Elon Musks and Peter Thiels of the world.” — Kaitlan Collins

There have always been wealthy people who want the status, influence, and attention you get from press ownership. “You’re asking if vanity and ego are still a thing in the world, and they will always be,” says one executive. The difference today is that media properties are no longer very good businesses, which means they often attract the interest of a different kind of rich person — either charitable or, possibly, delusional. Both types have a mixed record of late.

“I don’t think they’re serious players in the business sense,” says Hamish McKenzie of the current class of media benefactors. “I think they’re just owning — they’re picking up formerly prestigious brands as trophies for their shelves.” Billionaire ownership “keeps some people employed, and it keeps these loved institutions alive in some ways,” he says. But the publications supported like this “are mostly just on life support. They’re not actually major cultural players anymore.”

A billionaire owner “certainly makes it easier to have time to figure out your options,” says Politico’s John Harris. Because of that, a wealthy white knight is something many people working for financially shaky high-status operations are hoping for. “Someone will always take their money,” says Janice Min, likening it to the Medicis’ patronage.

But eventually, the good feeling wears off and the Medicis begin to resent their endless check writing to self-regarding journalists unwilling to adapt. “I haven’t really seen many billionaire benefactors who are kind of indifferent to the business performance of the property,” says Harris. “That’s just not the way it works,” adds an executive. “Marc Benioff wants Time to make money. People don’t get that because they think people much richer than them stop caring about money. Actually, that’s not the case. It’s people who are much richer than them who care obsessively about money.” Though they are often more patient than, say, venture-capital firms, eventually their charitable impulse runs low. “You don’t become a billionaire by letting your properties lose money indefinitely,” notes another executive.

Besides, having such support can, in that sense, be stifling to the business model. “The Washington Post and the L.A. Times are obviously the real case in point here,” says an editor-in-chief, “where billionaire ownership meant they never really took seriously building a business. And at some point, the billionaires get bored with that.”

“Just once, I would like to see a billionaire-backed business model in media, as opposed to just a billionaire subsidizing a broken business model,” says Jeremy Boreing.

“It’s high on my list of organizations that have stumbled,” says Stephen Engelberg. Many people felt it was in a strong position compared with other regional papers — if nothing else because the region is so wealthy and influential. “I don’t think they figured out how to be indispensable in California,” notes a top editor. “I think that they tried to be a smaller New York Times, but there already is the New York Times,” says another top editor.

“Ownership is important. Never underestimate that, as they say. It’s a cliché, but it starts at the top,” says a veteran newspaperman. In 2018, Patrick Soon-Shiong, a biotech billionaire, bought it. “I think what happened there was a well-meaning but way-in-over-his-head owner who was basically extorted to rescue a beautiful but nearly doomed hostage for $500 million or whatever,” says an editor-in-chief. Then he put more money into it but didn’t fix the problems. “It’s gone wrong over too many years. The unionization has made everything more expensive. Print is dying, yet the staff is so not digitally focused enough,” they say. “The staff really didn’t have the skill sets necessary to achieve a turnaround. And the New York Times, by the way, in 2008, didn’t have those skill sets either, but it managed people out who refused to change it, bought out a whole bunch of older people, hired a whole bunch of new people, and then did not lay them off as the L.A. Times did.”

In 2021, Soon-Shiong hired Kevin Merida as editor, but he left early this year; it has been reported that the two clashed. Others in the newsroom have complained about the owner’s very progressive daughter taking too close an interest in the paper’s coverage. (The paper has since cut 20 percent of its newsroom.)

Another thing it never did: As the Hollywood trades went digital (with Jay Penske buying up Variety, The Hollywood Reporter, and Deadline) and The Ankler and Puck competed for the insider, the L.A. Times didn’t become a player in that — its home market. “Everything about them is so ideological, flat,” says a media executive. “I remember ‘Are Freeways Racist?’ as a perfect example of an L.A. Times story.”

So what is to be done? “My hope is that the L.A. Times fights its way out and follows more of the path of the Boston Globe,” a regional paper that has a solid digital subscription business, says another media executive. “But there’s kind of a cycle where you lose your best writers, you lose your best people, then you start to do things to try to make your model work, and then you’re in a real problem.”

It wasn’t so long ago that the Washington Post was on a roll with Jeff Bezos’s checkbook backing up Marty Baron’s editorial leadership. Bezos bought the Post in 2013 for $250 million after the paper’s lack of digital strategy — both Vox and Politico were founded by Post refugees — put its future in peril. He invested deeply to expand the newsroom. At the height of the so-called Trump Bump, under its “Democracy Dies in Darkness” slogan, digital subscriptions surged. But some argue the chaotic newsmaking presidency of Donald Trump masked a host of shortsighted business decisions. “The Post and the Times had a huge run-up during the Trump administration, and the Times used that time to diversify into games and health and lifestyle items, cooking, and the Post just acted as though this moment would last forever,” says a magazine editor. But after that, unlike the Times, the Post didn’t have a plan for what to invest in next that wasn’t politics, and after Baron left and was replaced by Sally Buzbee — then-publisher Fred Ryan’s pick — even that coverage seemed to lose its edge.

“They hadn’t built a sustainable editorial model that could support itself, post-resistance Trump era. And they hired some of the wrong people,” says another media executive. Meanwhile, the Post missed out on the arrival of a new era of political and policy coverage, allowing competitors to crib its audience.

“The Washington Post is screwed. They screwed themselves, maybe eternally,” says a digital-media executive. “Gross mismanagement, lack of a strategy, crappy culture, complex unions, allowing too many people from Politico to Axios to the New York Times to own categories they once had a chance to own.” As Bari Weiss says, “They should dominate D.C. They should get every scoop related to the federal government. And they just don’t.”

Even Bezos’s efforts to fix it of late have led to more tumult. This summer, it came out that his new publisher, Will Lewis, who arrived at the top of the year, had tried to shunt Buzbee into a new gig running a “third newsroom” focused on service and social-media journalism. But Buzbee quit, and Lewis’s hand-picked crony replacement for her, a Brit named Robert Winnett, was forced to step back after accusations of being too Fleet Street. Another onetime Lewis associate, Matt Murray, earlier replaced in the top Wall Street Journal job by Emma Tucker, was brought in to be interim editor. Now, many people think he’ll just end up staying on.

“I think what’s going on at the Post is a little concerning. This talk about a third newsroom, I don’t really understand it,” tsk-tsks a rival top editor. Others are less harsh. “I think the third-newsroom idea is great. Terrible branding, but it’s smart,” says a media executive. “The current commercial side of the Post is run by people who understand the subscription model. I think it’s much more clear now that they are focused,” says an editor. And as Ben Smith notes, “the Washington Post is still the Washington Post. Washington is still a place. Political news is still a thing. I think they’ll ultimately find their way to buying Punchbowl and trying to eat Politico’s lunch.”

The rumor right now is that Will Lewis wants to get Jeff Bezos to open his wallet. That would be a throwback to 2021, when Axel Springer bought Politico for about $1 billion, and 2022, when the Times bought The Athletic for $550 million and Cox Enterprises dropped $525 million on Axios. The last two are viewed skeptically today. The Times continues to lose money on The Athletic, and, according to one media executive, “Cox way overpaid, and Axios doesn’t make any money.” (Earlier this year, Axios laid off about 10 percent of its workforce.) Not that Axios, which was founded by Politico and Post vets Jim VandeHei and Mike Allen (along with Roy Schwartz) in 2016 to create essentially a PowerPoint presentation of news (a.k.a. “Smart Brevity”), doesn’t have its defenders. “In moments of peak political excitement, Axios AM is still a version of the Times homepage to me,” says Jon Kelly. But as Janice Min notes, “Not to be dire, but it feels like Axios and The Athletic are going to go down as the two luckiest places that got hundreds of millions while you still could.”

If it can only reach a truly elite audience and get enough of them to come to live events.

Semafor, founded by Ben Smith and Justin Smith in 2022, fancies itself a global news organization with a small team of journalists based in the U.S., Africa, and, most recently, the Gulf. “What I’m seeing is a curated, cost-effective, focused approach to thinking about how to share and talk about content,” says Matt Murray, “and a careful approach to growth. And it’s telling me something about how news is evolving.” Semafor launched having raised $25 million from various rich people, and because of the prominence of the Smiths in the business, many people signed up for its newsletters. Semafor’s scoops, when they come, often have resonance. But it’s still scrappy. Events — curated live journalism gatherings featuring heavy hitters across politics, business, and tech — turned out to be half of their business. Semafor claimed to have achieved several months of profitability in its first full year, with 50 percent of revenue coming from events, and last year made more than $10 million in revenue, split between advertising and events. Semafor also struck a deal with Microsoft, which is sponsoring an AI “breaking-news feed.” Early reports said the Smiths had planned to evolve into a paywall model, but they haven’t done so yet; instead, they are grabbing revenue where they can.

“We have to be careful about not using the ‘in peril’ narrative too much, where people will think it’s already all dead and there’s nothing left to save,” says CJR’s Sewell Chan, who spent three years running the nonprofit Texas Tribune. Chan points to two bright spots in efforts to support local news: the National Trust for Local News, which acquires vulnerable community papers and invests in their development, and the American Journalism Project, which tries to rebuild local news by seeding local digital start-ups.

Audience interest in local stories is high, Apple News has found. “That’s part of what we’re trying to do — connect local news outlets with their audiences again,” says Lauren Kern of Apple News. “After the Apalachee school shooting earlier this fall, we relied on the Atlanta Journal-Constitution for coverage,” she notes. “The North Dakota state abortion ban was ruled unconstitutional, and we have the North Dakota Monitor to literally put at the top of a national news app.”

Among other experiments are small, sometimes worker-owned or nonprofit newsrooms around the country. San Francisco has 27 news organizations — about the same as it had a decade ago, thanks to a mix of nonprofits, radio stations, and, yes, the largesse of various rich people, of which the city has no shortage. In New York, there’s the swashbuckling Hell Gate and the more self-serious nonprofit The City. But there’s also the Murdoch-owned New York Post, which has survived by becoming, as its editor Keith Poole puts it, “a national digital brand.” That means it peddles national news, tabloid sensationalism, gossip, and Fox News–adjacent talking points that make it sometimes seem to despise the very city it’s based in. “We have to treat our news very differently locally and nationally. Not all readers will necessarily be interested in education policy in New York City,” Poole says. “We’re profitable — little-known fact. We’ve been profitable for the last three years in a row.”

The biggest threat to local news is hedge funds like Alden Global Capital that have gobbled up and then gutted regional papers across the country. “These are either zombie newspapers or soon-to-be-zombie newspapers. I don’t know if they’re going to make it,” says Stephen Engelberg.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution, though, is owned by Cox Enterprises, a family-owned company that gave the paper a multiyear building plan. “There’s a difference between managing decline and investing in transformation,” says editor Leroy Chapman Jr. But, by and large, “the business model for local news is broken. It really is,” he adds. “There has to be, among the public and among elected officials, a recognition of how vital local news is to thriving communities” and “public investment” in protecting it. “We need some help to have a business model that lets us recoup fairly what we should, based upon what we produce, and that will provide the sort of thing our democracy needs, which is objective fact.”

“It’s like a digital version of a classic magazine. So that’s really a different kind of delivery. I think they can be a really valuable contribution to the voice, and I think they can be interesting. But I think (1) the economics are still tough, (2) the audience growth may be limited, and (3) it’s a lot of work to keep them interesting and hustle your audience and keep them engaged and keep them going.” — An editor-in-chief

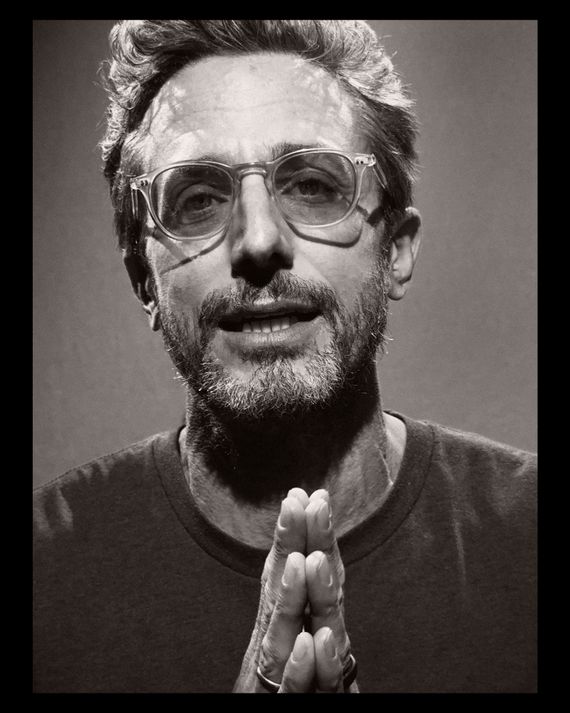

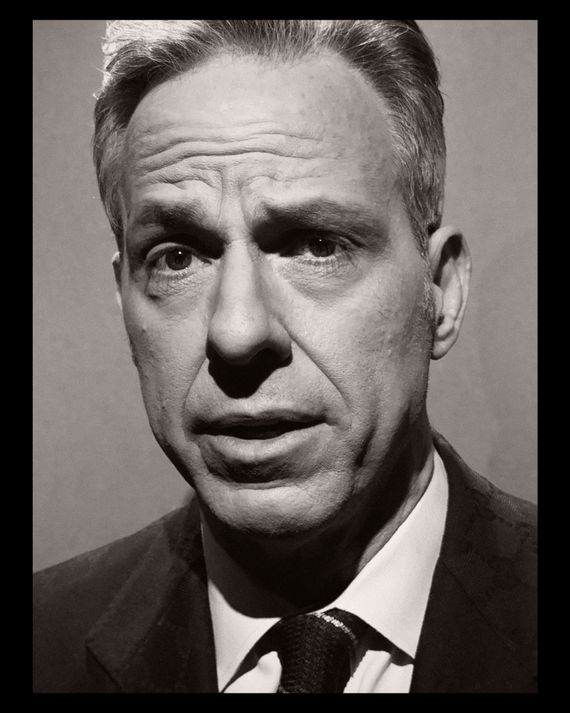

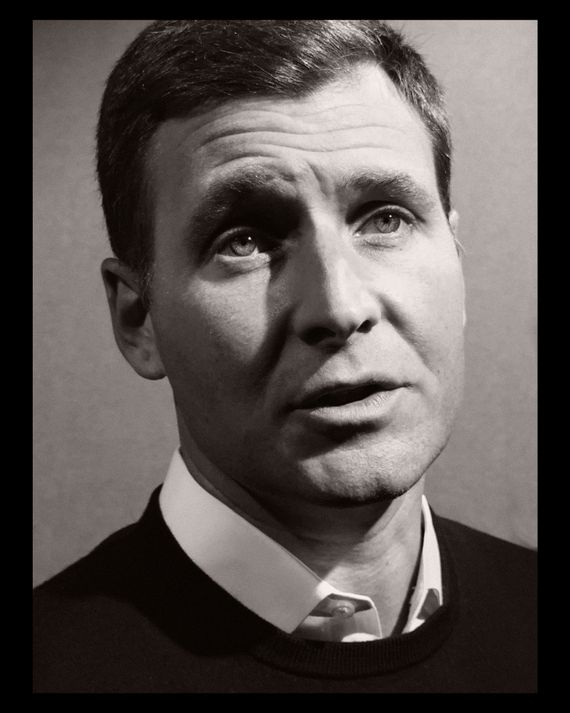

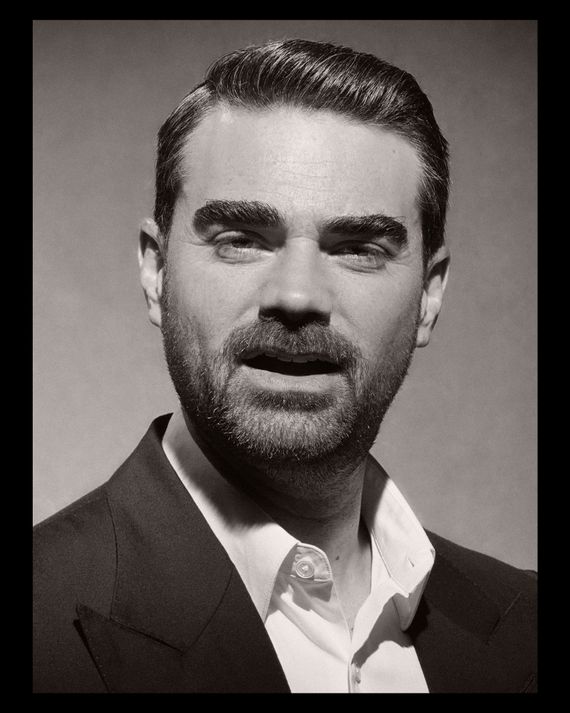

From left: Jeremy Boreing, co-founder and co-CEO, The Daily Wire. Matt Murray, executive editor, the Washington Post.

From left: Jeremy Boreing, co-founder and co-CEO, The Daily Wire. Matt Murray, executive editor, the Washington Post.

From left: Alison Roman, writer and chef. Jon Kelly, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Puck.

From left: Alison Roman, writer and chef. Jon Kelly, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Puck.

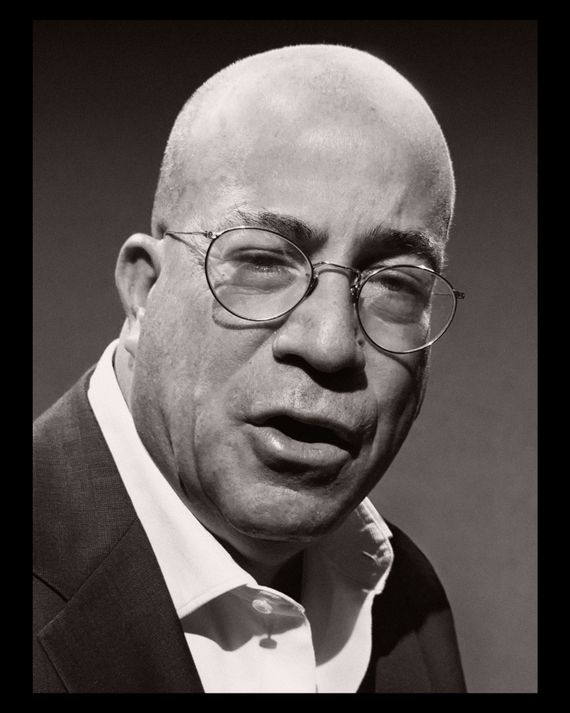

Neal Mohan, CEO, YouTube.

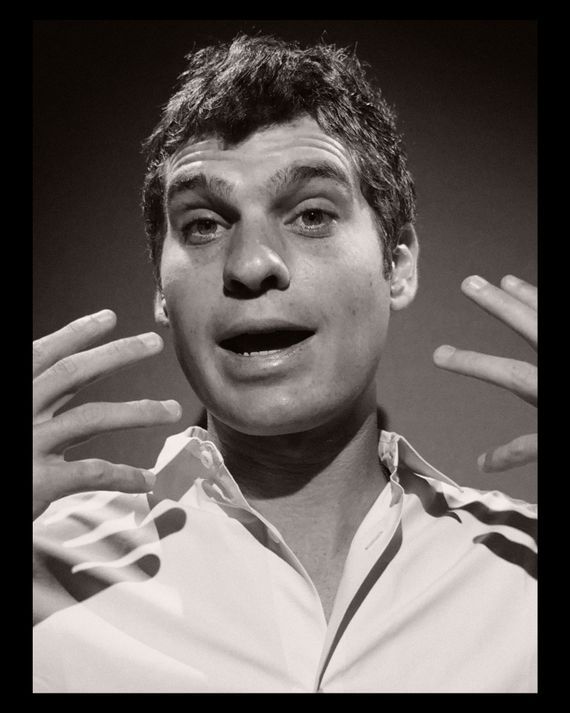

From left: Ben Smith, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Semafor. Simone Swink, senior executive producer, ABC’s Good Morning America.

From left: Ben Smith, co-founder and editor-in-chief, Semafor. Simone Swink, senior executive producer, ABC’s Good Morning America.

From left: Wendy McMahon, president and CEO, CBS News and Stations and CBS Media Ventures. Jim VandeHei, co-founder and CEO, Axios; co-founder, Politico.

From left: Wendy McMahon, president and CEO, CBS News and Stations and CBS Media Ventures. Jim VandeHei, co-founder and CEO, Axios; co-founder, Politi…

From left: Wendy McMahon, president and CEO, CBS News and Stations and CBS Media Ventures. Jim VandeHei, co-founder and CEO, Axios; co-founder, Politico.

From left: Sam Dolnick, deputy managing editor, the New York Times. Kaitlan Collins, anchor, CNN’s The Source.

From left: Sam Dolnick, deputy managing editor, the New York Times. Kaitlan Collins, anchor, CNN’s The Source.

From left: Ben Shapiro, host, The Ben Shapiro Show; co-founder, The Daily Wire. Samira Nasr, editor-in-chief, Harper’s Bazaar.

From left: Ben Shapiro, host, The Ben Shapiro Show; co-founder, The Daily Wire. Samira Nasr, editor-in-chief, Harper’s Bazaar.

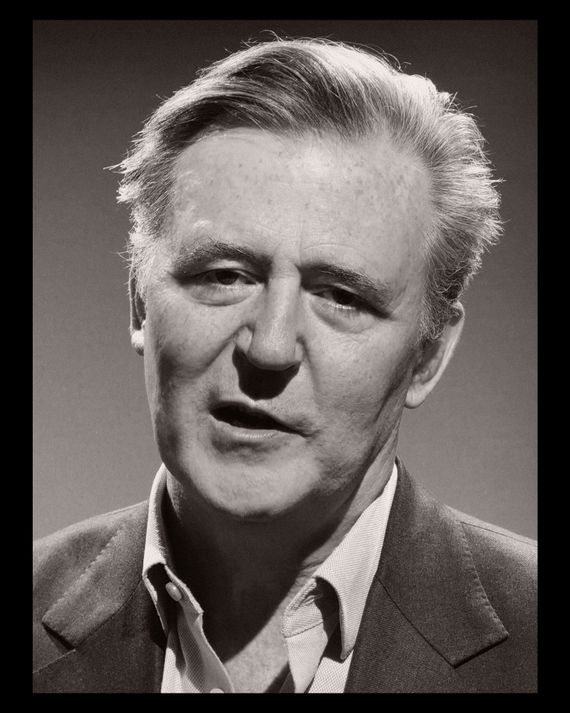

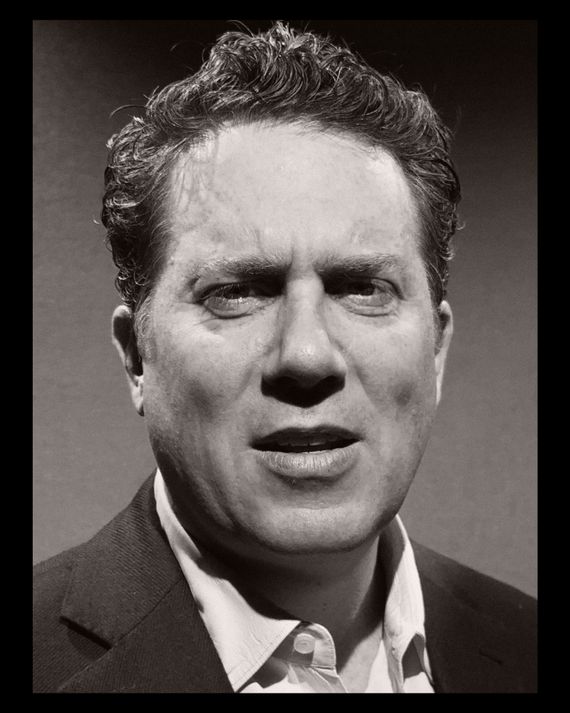

Graydon Carter, founder and co-editor, Air Mail.

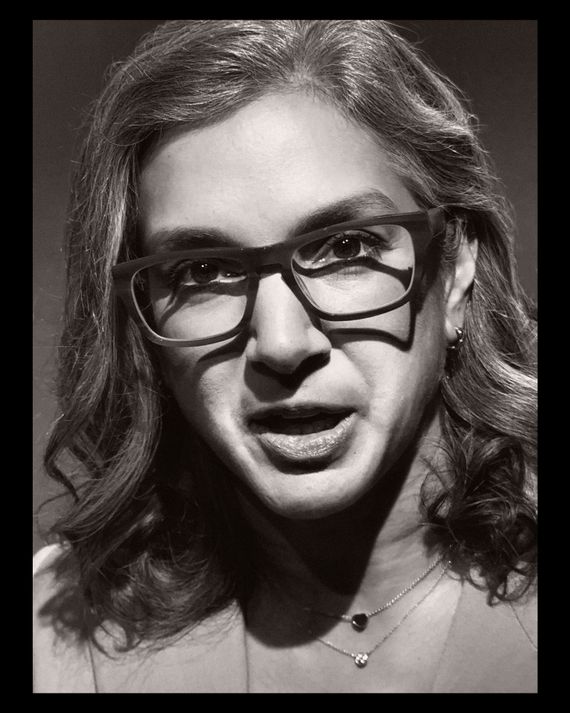

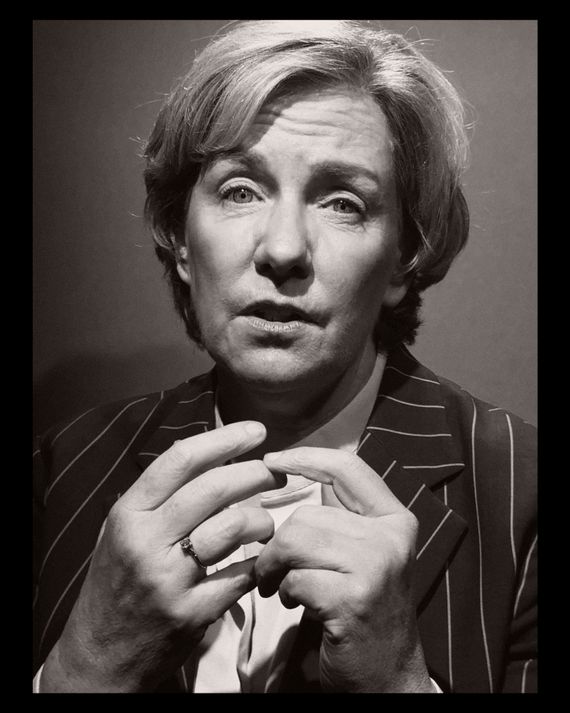

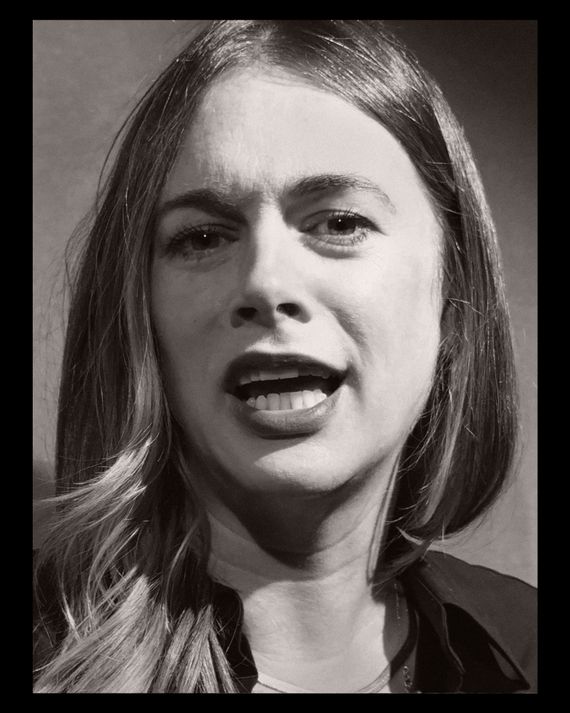

Willa Bennett, editor-in-chief, Cosmopolitan and Seventeen.

“Beats the shit out of me.” — Jim VandeHei

“Oh, you’re funny. Any media operator who looks at the unit economics of print will have a hard time answering that question.” — Jon Kelly

It’s not completely obsolete and has become a way for publications to attract and retain subscribers and lure in both celebrities and high-end writers who still care about appearing in print (just the other week, The Atlantic announced it was upping its frequency from ten to 12 print issues a year). And magazines are still riding the pandemic luxury-fashion boom; those fashion advertisers are hungry for glossy pages to appear in.

“Print is a luxury item.” — Mel Ottenberg, editor-in-chief, Interview magazine

“I’m trying to think of what to say instead of ‘a business card,’ but it really is like a business card. It’s a manifesto for what your brand stands for.” — Willa Bennett

“We obviously care deeply about print, but in terms of growth, it’s not where our focus is.” — Emma Tucker

“Keanu Reeves, Frank Ocean, Rob Pattinson, Beyoncé — they are not coming to a GQ Instagram shoot.” — Will Welch, global editorial director, GQ and Pitchfork

Magazines Still Need Celebrity Covers …

“It’s an incredible point of access, and it gives us the opportunity to create an iconic image with a point and a purpose and a message that then permeates all our other platforms. Chappell Roan was shot by Inez & Vinoodh, and she’s at this incredible moment in her rise in her career, and it’s a deep interview and the writer spent days with her, and without print, that wouldn’t have happened. And then there’s video and all these other assets. Print is the tip of the spear, but the majority of it is digital. The impact of it, the symbolism of it, opens a door for us. That’s really, really critical.” — Gus Wenner

And the Celebrities Still Need Them, Too.

“Magazines may not be as important as they were a decade ago, but the fight to get on covers has never been greater. And that’s because there are ten times as many famous people now as there were a decade ago. And on average, each of them is one-tenth as famous with the exception of Taylor Swift. There’s a lot of people clamoring to be recognized and to get that cover.” — Bryan Goldberg

“Having a cover of Vogue or Vanity Fair or doing something that might change their image, or doing something that might be a breakout, Star Is Born moment for them — being on the cover of W, for instance — where it kind of casts them in a new light, perhaps an edgy light, I still think it has a lot of impact.” — Eva Chen, vice-president of fashion, Meta

“It’s an endorsement, and it’s a certain degree of validation that you don’t get if you just stay on your own channel and in your own world.” — Samira Nasr, editor-in-chief of Harper’s Bazaar

Celebrities, Though, Now Have the Upper Hand.

“Some people would say to you [after seeing the Beyoncé GQ cover, for which she conducted the interview with the writer over email], ‘Well, at least she gave them an email interview.’ Normally, she doesn’t talk. Other people would say to you it’s a real demonstration of how traditional media brands like GQ and Vogue have lost their power to call the shots in interviews like that. And the truth is those media brands, they really rely on those big covers to generate conversation and to telegraph their power and influence, which are undeniably waning in the era of social.” — A digital media executive

“It’s Not Enough to Just Have a Cover.”

“I do think that having a really sophisticated and 360-degree approach to a cover and to a moment and to an issue is critical. It’s not enough to just have a cover. You have to think about what is the real strategy — what are the sound bites that will be everywhere on Reels? Like, any magazine that is not sending a social-media person on set for the cover to get behind the scenes is frankly behind.” — Eva Chen

But Also, What Even Is a Cover Anymore?

“The state of the fashion-magazine cover is somewhat diluted by the fact that anything can be a cover. So anyone could put a big logo on an image and call it a cover. And brands — even really, really prestigious media brands — are doing digital covers, whatever that means, right?” — Imran Amed, founder and editor-in-chief of The Business of Fashion

Resuscitations and expansions of print products announced in the past 12 months: The Atlantic, Complex, i-D, Life, Nylon, Saveur, Sports Illustrated, and Vice.

Editors perhaps envious of the publisher’s resources through the years had a lot to say about how it squandered them. Here’s one such tirade from an anonymous executive.

“I mean, Condé Nast is the most pathetic company I’ve ever seen in my life. They’re so stupid. And some of it is like the hubris of 1990s media. You’re sitting there, believing you rule the world, not knowing the world has completely changed and fallen out of your grasp, but you still conduct yourself with an arrogance that eventually the market rejects. It is so bananas, and the fact that they don’t change that whole model there is wild. They think their brands mean more than they do, and therefore they approach the market with an hauteur around sponsorship and ad sales, and yet they have turned all the content into content-farm stuff at the same time out of necessity.”

(Roger Lynch and Anna Wintour declined to participate in this project.)

Despite cord-cutting and aging demographics, the people who make TV news seem confident they’ll find a way to keep doing pretty much what they’re doing — while finding new ways to distribute it.

“The bottom line is that the total time spent with our original programming across television and streaming combined is actually up year over year,” says CBS News’ Wendy McMahon. “When you look at the total time spent — with the lion’s share of it still on television — it’s still a reach vehicle. Are there declines? Yes. Is it relatively stable? Yes.”

Says another TV executive, “In terms of viewership and availability, news is more successful than ever because it’s more available than ever. You can access news on all platforms, not just linear, but through social-media platforms from Twitter to Facebook to getting your news on TikTok.”

But no one knows what’s next, exactly. “Something big is about to happen,” says another top TV executive. “There’s no doubt about that, whether or not megastreamers become the platforms for some of these news divisions or networks decide just to provide some of their content to the streamers. There’ll be some sort of consolidation.” A senior TV executive says, “You could see a combination of tie-ups, perhaps with some of the streamers. It would be really interesting if Netflix or Amazon decided to go into news.” “I think the legacy in the brand helps a lot,” says 60 Minutes executive producer Bill Owens. “We haven’t deviated or changed. It still looks the same. The story selection is the same.”

In other words, steady as she goes. “Well, the path forward for CNN, I think,” says anchor Jake Tapper, “is for us to keep doing what we’re doing and providing an attempt at fair and objective news that is not ideologically driven. And I think that’s the recipe for ABC, CBS, NBC, and PBS as well. How do we keep that going in this world of cord-cutting and smartphones and a million new sources and the like is for bigger brains than mine to figure out.”

“Why is an anchor on a television network making between $10 million and $20 million a year, but a similar talent on social media doesn’t enjoy the same revenue and salary opportunities? There are structural reasons in the business that have explained that, and they’re shifting really quickly. And I think that these are as important in many cases as the story that these companies tell.” — Jon Kelly

“The days of these ridiculous anchor salaries have to be over. It’s not worth it. The business model doesn’t support it any longer. If you were to combine all the GMA anchor salaries, I guarantee you their news-gathering budget is less than that.” — A TV executive

“Rachel Maddow’s deal would not happen today. If I’m paying you a ton of money, then I expect you to be everywhere. I expect you to be on in the mornings, to be in prime, to do that podcast, to host this event. There’s a bit of an ROI that should be part of this process.” — A news executive

“Networks will always figure out a way to pay when they want to pay … No one has ever said to me, ‘They slashed my salary.’”

Younger people don’t tend to watch network TV or pay for cable. Instead, many have grown up getting their news on YouTube. News divisions are following them. Take ABC: It isn’t “producing vastly different content for YouTube, but we are hitting nearly 18 million subscribers,” says ABC News president Almin Karamehmedovic. “The demographic is way younger than what we have on linear television.” Which suggests that the problem for TV news is not so much what they make as where they put it. “The main thing we do is distribute their content in a way that users, especially younger users, want to consume it,” says YouTube CEO Neal Mohan. “We built products that cater to that news use case. So we have the breaking-news shelf when there’s a big event happening. We have top news and search results. We have a local-news shelf.” And not just TV news: “If we do a successful video, its views on YouTube just dwarf its views on our platform,” observes one newspaper editor. Along with podcasts, it’s another way to reach people. “The surge of video podcasts — people wanting to spend more time on their screens and wanting to watch somebody staring at their screen — was a big surprise to me,” says Sam Dolnick. Charlamagne Tha God, whose radio show is also a YouTube hit, says it’s about adaptation. “Television has evolved into what people are watching online,” he says. “It is just viewing habits, right?”

When we asked what the most common misconception about the media is, we heard the same thing over and over again: “That it’s all an interconnected corporate conspiracy with an agenda to propagandize,” says Washington Post executive editor Matt Murray. The reality, says Guardian US editor Betsy Reed, is that the way a big story gets covered in the “mainstream media” (meaning, journalistic entities not specifically aligned with the left or the right) “is really about individual reporters and editors making the decisions they think are right in the moment. And if that then ends up meaning there are 17 stories published on the same day, that doesn’t necessarily mean that was a plan by the editor. It’s the way things played out in a newsroom, which is composed of a lot of people who are generally trying to do the best, most responsible job they can in the moment.” Or as Graydon Carter says, “Some people in the political spectrum think that individual parts of the media work in dramatic concert with each other, and that’s just simply not the case. In reality, it’s a million mice running around in a cage, all with different trajectories, and all with different goals.”