Photo-Illustration: Intelligencer; Photos: New York Post

It’s hard to argue that the New York Post is exactly what it once was.

After Rupert Murdoch bought it and remade it in his Fleet Street image in 1976, the city woke up each morning faced with its brazen, often hilarious front page (a.k.a. “the wood”) and the fearsome, must-read “Page Six” gossip column. Everybody read it, from cop to CEO, and for decades it was the paper of record for the city’s id, helping set the agenda for the rest of the coverage, from glossy magazines to the nightly news, in the media capital of the world. Today, with information and outrage coming from a million different directions into your phones, that power is less so; the Post can often feel like it is playing catch-up to the internet. But by becoming more of a national tabloid — with lots of gossip, scandal, and right-wing spin — it’s doing better than most local newspapers, and even, in recent years, has claimed to be profitable.

Last month, I met up with Susan Mulcahy and Frank DiGiacomo, two New York Post veterans — Mulcahy from 1978 to 1985, DiGiacomo from the late 1980s to 1993 — who are out today with a 528-page oral history of the Post. We chatted over coffee at the Odeon, where copies of the New York Times, the Daily News, and, naturally, the Post were proudly — and somewhat anachronistically — displayed on the restaurant’s magazine rack, throwbacks to an era when everybody wasn’t just staring at their screens. Their book, Paper of Wreckage: The Rogues, Renegades, Wiseguys, Wankers, and Relentless Reporters Who Redefined American Media, tells the story of the Post during the Murdoch era through the voices of more than 230 current and former staffers who lived it. (Read an excerpt here.) “I feel like we’ve got sort of the pros, cons, the good, bad, and the ugly,” says DiGiacomo, whose oral history of “Page Six” for Vanity Fair in 2004 formed the basis for part of the book project, which was originally Mulcahy’s idea.

You’re both quoted in your own oral history.

Frank DiGiacomo:

Yeah, well, we were kind of inspired by the [George] Plimpton book on Edie Sedgwick. And he’s in that.

Susan Mulcahy:

We didn’t want to put too much of ourselves in. Several of my quotes in our book are from Frank’s Vanity Fair piece. Then there were a couple places where we were putting this whole thing together about outrageous Steve Dunleavy drunk stories. And Frank and I are talking about it. I’m like, “I’ve got one. I’m going swimming at this health club and Dunleavy …” Then Frank had a very different experience covering Trump than I did because it was so much later. So that was appropriate for him to put in his experience covering Trump. I don’t think we’re in it that much.

When did you work at the Post?

Mulcahy:

I was there in ’78, so I wasn’t there when he first bought the paper, but I was there a year later. There were a lot of things I liked about working there, but there were many things I hated and I wanted to get out. At a certain point, I was trapped. I left town for ten years in part because I just felt like I was typecast by New York. So it just was like “Page Six,” “Page Six,” “Page Six.” But there was some of it, the political incorrectness, yes, some of it was offensive, but some of it was kind of funny … There were also no women in positions of power in the Murdoch era. It was all guys.

DiGiacomo:

I was hired for a tryout on “Page Six,” and I was part time forever.

What was it like then?

DiGiacomo:

Working on “Page Six,” you get this map of the power grid of the city and you see who’s pulling strings where. I don’t think I could have had the career that I had afterward if not because of that. I knew who to call. I had a huge rolodex, and it just was good. I mean, working for [longtime “Page Six” editor] Richard Johnson, who is a very underrated editor and a very funny guy to work for. People would call him, and he goes, “I got it, it’s at the bottom of my pile.” And he had great stuff. So there was that. I also learned you learn to take very complex stuff and condense it, which is very helpful now in this age.

Mulcahy:

We checked out everything. When we would say “Rumor has it,” it was not a rumor. And “Page Six” was checked more, not only by the lawyers, but Joe Rab, who was a very long-term features editor there, was the final read.

Did “Page Six” feel all powerful then?

Mulcahy:

“Page Six” was sort of an entity unto itself. So the power of “Page Six,” it was amazing to me, the politicians — I went to the White House Correspondents’ Dinner when there were no celebrities there. Trust me. Or the Inner Circle dinner. Have you ever been to that? Sometimes it can be amusing. It’s a big local political dinner. And the mayor always gets up onstage, whatever. And these politicians — they knew who I was, they all read “Page Six” — they’d have comments, and you’d get calls from their adviser. I don’t remember that I ever got a call from a specific politician yelling at me but from their advisers and political consultants.

DiGiacomo:

Sean Penn — who then was at the height of his fame — calling to ask to “please don’t write this.” Or Mickey Rourke calling to say he was going to kick Richard Johnson’s ass. You had these people reaching out, and you were like, Okay, people are reading this. Robert De Niro called me a “fucking prick” once.

What happened?

Mulcahy:

It’s different now. I mean, I still read “Page Six” and enjoy it and everything. But when I was doing it, it was like putting together a mini condensed version of a newspaper or magazine — media, politics, entertainment, Wall Street, society. You had to have a little bit of everything. You had to have a real balanced mix. And if you didn’t have any entertainment stories, you had to come up with one, because it had to be balanced. It was very powerful at the time.

DiGiacomo:

The problem is that once the age of the internet hit, you had all of these sites coming up that were specialized. All of the subjects that “Page Six” covered and put together on one page were suddenly being taken away … And I discovered this when I went to work briefly for the Daily News. Once traffic became important, it just became about reality TV and the Kardashians. And I think it just sort of gives the sameness to things. But I will say this about “Page Six”: They get Elon Musk on the phone.

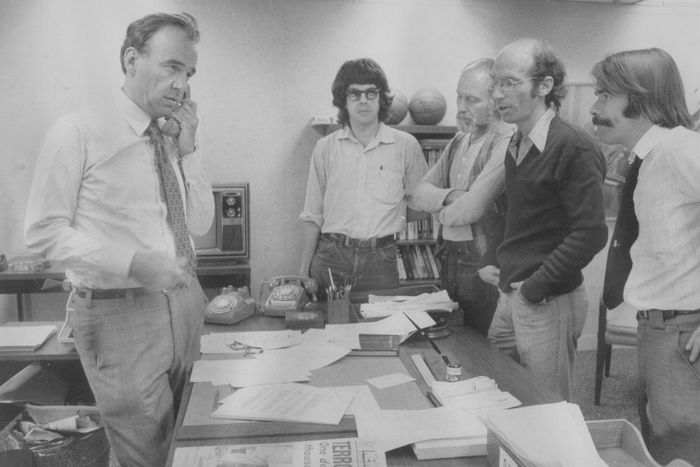

Rupert Murdoch directs coverage in the Post’s newsroom, 1977.

What was it like to cover Trump in the early days?

DiGiacomo:

Exhausting. I mean, that was really the heyday. It was the time of the “Best Sex I Ever Had” cover. And you would just be bombarded with stuff from all the desks. They were getting these tips, and they would come to you. And if the competition got it, and you didn’t, whether it was true or not, it just was like, “How did you miss that?” So that was a great deal of stress, and I was just exhausted by him.

How important was the Post in his rise?

DiGiacomo:

I can’t say the Post was solely responsible. I mean, because of the competition between the News and the Post, everybody wanted a piece of this. I think that’s why the Trump-Ivana-Marla thing still holds the record for the most woods in a row. It’s my theory that Trump learned to speak tabloid, which he still uses to this day — these very short, sort of general sentences that are exaggerated.

Has the Post lost too much of its New York–ness trying to make it on the internet?

DiGiacomo:

I do think that at least for the first period that Murdoch owned it, the Post did define New York. Graydon Carter says that when he came to New York, he read it to sort of know what he needed to know in the city and — especially with “Page Six” — the people he needed to know. And Letterman used it. Saturday Night Live used it. So I think it really defined New York then. And again, I think when he got it back, after breaking the union and stuff, there was that period in the sort of late ’90s and early 2000s where, again, it was really good at sort of capturing the Sex and the City era of New York. Now, I just feel that a lot of it is just creating fear.

It seems pretty obvious that Rupert Murdoch is less involved in the paper than he used to be.

Mulcahy:

He’s got so much else going on, and has had so much else going on, for such a long time. And at this point, it’s probably age. But you see, we had the anecdote that starts the book, when things were not going the way he wanted them, when Xana Antunes was the editor, he showed up at the editorial meetings and really chastised her in a public way.

DiGiacomo:

I think he gets involved when there’s an election at stake. I really do think that that’s when he’s really in it.

Mulcahy:

Although Gary Ginsberg told us that when Col Allan was the editor, he and Murdoch talked every day. So does he still talk to Keith Poole every day? I kind of doubt it, but I don’t know.

How did you go about asking people to participate?

DiGiacomo:

I think what was surprising was that a lot of people wanted to tell their stories. And the other thing that was very surprising is that even people who had been fired would say, “This was the best job of my career.” And there were those people who were difficult and some people just wouldn’t talk to us. And I think a few had NDAs or some issues —

Did you try Murdoch?

DiGiacomo:

Oh yeah.

Mulcahy:

We had his secretary’s email, which is way better than going through the PR person. And she strung us along for — how long? I don’t want to say “strung us along” — that’s not fair. But she didn’t say “no.” And so it was like at least two months, if not three. And I get these emails saying, “Well, I haven’t spoken to him yet. He’s out of the country.” Then, ultimately, I got a call from the PR people, and I thought, Okay, that’s the end.

DiGiacomo:

The other thing, I mean — it was frustrating, but I think understandable — was we approached a lot of celebrities who were stories and, to a person, except for Candice Bergen, they said “no.”

Mulcahy:

Well, we got John Waters and Isaac Mizrahi.

DiGiacomo:

It’s my opinion that no one wants to piss off the Post.

Mulcahy:

Alec Baldwin did talk to Frank for Vanity Fair but not for this book. No, he wouldn’t talk to us. Weird.

DiGiacomo:

Well, he was also going through a lot of legal stuff at that point.

Post legend Steve Dunleavy with Joey Buttafuoco

Photo: Ron Galella, Ltd./Ron Galella Collection via Getty

What was the biggest challenge of doing the book?

DiGiacomo:

Well, I mean, constructing an oral history is super-hard. And we talked every Monday to sort of discuss, first, how are we going to break this up? Then what would happen was we’d each sort of work on chapters, then switch and add things, then we each sort of edited the chapters.

Mulcahy:

At the beginning, we did talk about — and we ran this by our editor — we were like, “Should we do a Dunleavy chapter; should we do headlines?” We did do a headlines chapter, but it worked chronologically. And at one point we had dates for every chapter. This chapter is ’78 to ’79, and it just didn’t work because we had so much, so what we ended up doing is breaking it into sections.

DiGiacomo:

I find it very frustrating when I read an oral history and it’s just quotes. Because you’re like, Where am I in the story, and the subjects keep changing? I mean, I do feel like we really worked hard to make this flow, if not exactly chronologically, close to it.

And also in the book people are — without knowing, obviously — in conversation with each other, just based on the way you’ve ordered it, which is so much fun.

Mulcahy:

We made sure we went back to everybody … Some of these phone calls were very difficult to make. I really like Peter Vecsey, and I like Phil Mushnick, but I had to call Vecsey and say, “Phil Mushnick says you’re a bully and a psychopath.”

And what was the best part about writing the book?

DiGiacomo:

While I was working there, I heard all these amazing stories and I was like, Are all these true? A lot of ’em were told at bars, and I was just like, “The stories are so great.” It was one of the reasons I pitched the Vanity Fair piece too. And the other thing, I mean, I was not exactly happy about it, but a lot of people we interviewed died because we were working during COVID. I feel a measure of pride that we got this stuff down. I don’t think the Post would’ve ever done it.

What’s your favorite story from the book?

Mulcahy:

I really got a kick out of so many of the Dunleavy stories. When I first started working here, I found Steve to be very funny. I enjoyed him as a character in the office, but he ultimately drove me out the door. I did not go to his funeral, but I did appreciate what a great character was. No one could believe he lived to be 81.

DiGiacomo:

Wayne Darwen’s story about Dunleavy having sex with his fiancée on a snowbank. I mean, that was a story that I’d heard forever. And it was like, “Can this really be true?” And it was.

Mulcahy:

The stories about the Christmas party in ’79. I was like a clerk on “Page Six” at that point — oh my God. The fistfights, the drinking, people just standing on desks and falling off. Then the next day, one of the two guys that got in the fistfight, Craig Ammerman and Daniel O’Donnell, one of them, I’m not sure which one, then got in his car, drove up on the West Side, then drove into the window of a big car dealership. I just thought, Wow, that’s not the kind of Christmas party I was expecting. So I love that my memory was valid because I thought I just remembered that being insane. And enough people who I talked to said it was like something out of a movie.

Looking back, do you miss it?

Mulcahy:

I think I had a love-hate relationship with the Post forever because I feel as though when I was a senior in college, when I started working there, I feel like I grew up there. Then doing this book made me appreciate some of the things that were positive about it. I’m still pissed off, but there was a little more positivity as I was remembering than at the time.

DiGiacomo:

I wouldn’t say it was necessarily a happy experience, but it was formative for me. And it really toughened me up as a reporter. And I also think that I was pretty naïve before I worked there. You lose that very quickly.

Mulcahy:

That’s true. You just have to have very thick skin.

Do you think the paper will survive after Rupert?

Mulcahy:

I don’t know that it’ll survive. If Lachlan becomes the definitive heir and the trust is broken up, I don’t think so. One person, Eric Fettmann, worked there for a long time. He says he thinks that Lachlan respects the Post brand and he would keep it going. But I don’t know. I don’t think the kids have the same attachment to it. That’s one thing that’s positive. Doing this book, we really learned there are obviously negative sides to Murdoch, but there are positive sides, and one of them is the guy loves newspapers. So that’s important. He also works really hard. That was amazing. People would talk about not only him in the office but calling — you never said to Murdoch, when he called in from wherever he was around the globe, you never said there’s nothing going on, because you would get an earful: “What do you mean?” You’d say, “We’re working on a great one.” If there’s a murder here, we’re following up on it. You never said there was nothing going on. So he really was very driven to have the paper be what he wanted it to be. But at this point, I don’t know.

DiGiacomo:

Yeah, I think you’re right. I think if Lachlan wins, there’s a chance. But if he’s not the sole, I think they’ll shut the Post down.

Mulcahy:

I think Lachlan will shut it down.

Source link