Photo: Laura Brett/SIPA USA

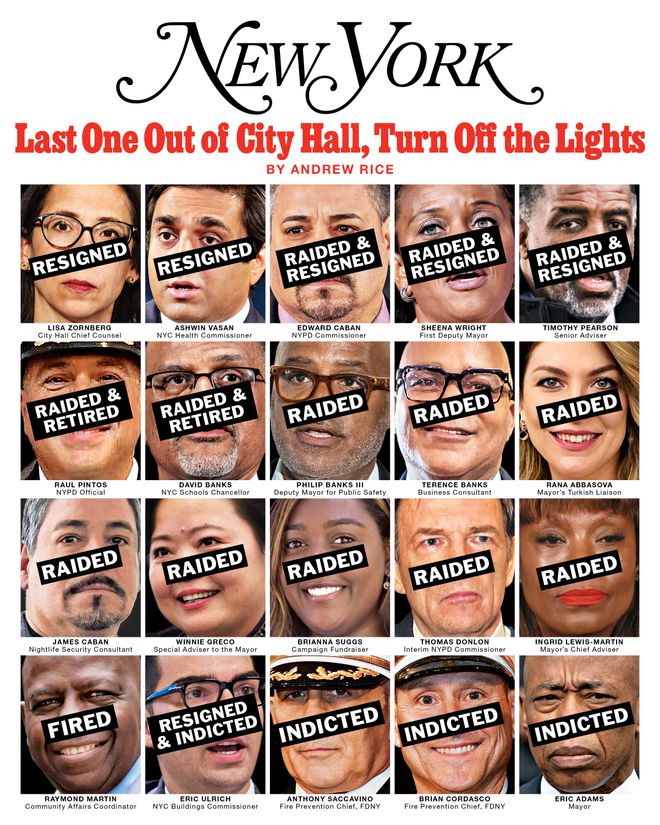

In mid-September, shortly after the New York City police chief resigned amid a federal criminal investigation and Mayor Eric Adams’s chief counsel quit, apparently because her client wasn’t heeding legal advice, and a couple of retired Fire Department officials were arrested on bribery charges, Ingrid Lewis-Martin disappeared from City Hall. Lewis-Martin had long been the most loyal and indispensable of Adams’s advisers — he brings the swagger; she swings the stick — so her sudden absence was noted in the building. “She’s not in this country,” one Adams critic told me. “I hear she is on a beach.” Questions kept bubbling up. Was she fighting with Adams? Was she cutting a deal with the Feds? Was she gone from City Hall for good?

In fact, Lewis-Martin was in Japan on what her attorney later described as a personally financed “friend trip,” sightseeing with a group that included the city official and former state senator from Brooklyn Jesse Hamilton, real-estate executive Diana Boutross, and former state assemblyman Adam Clayton Powell IV. “It was pure vacation,” says Powell, who chronicled his highlights — resort hotels, bullet trains, a night out in Roppongi, a geisha show — on Instagram. The whole time, though, Lewis-Martin’s phone was buzzing. One day, the FBI was searching the interim police commissioner’s house, reportedly looking for classified documents. The health commissioner announced he was on the way out the door and was soon followed by the schools chancellor, whose phone had been seized. City Hall reporters were pestering Lewis-Martin for comment. Rumors were rampant that the mayor was about to go down. On September 26, at around 10 a.m. Tokyo time, the news leaked that Adams had been indicted on corruption charges — a long-anticipated but nonetheless shocking moment in the city’s history.

The next day, Lewis-Martin flew home to a city on the brink of a municipal civil war. Some prominent officeholders, like Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, had already called for Adams to resign. Others wanted Governor Kathy Hochul to exercise a seldom-used power to remove him from office, which would trigger a snap special election. A half-dozen potential replacements were jostling for position — including Hochul’s predecessor, Andrew Cuomo, who was looking for a comeback express lane. It appeared certain that more arrests, more scandal, and more pressure would be coming. “We continue to dig,” Damian Williams, the U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, said at a press conference unveiling the Adams indictment. Investigators had conducted yet another search, this time at Gracie Mansion, earlier that morning. When Lewis-Martin and her travel companions arrived at JFK the next day, Powell heard a loud voice call out at Customs and saw Lewis-Martin pulled to the right. Two separate groups of investigators were waiting. The Feds served her a subpoena for documents, and the Manhattan district attorney’s office had a warrant for her phone. (The Daily News would subsequently report that Hamilton’s was taken too.)

Outraged and device free, Lewis-Martin went to see her criminal-defense attorney, Arthur Aidala, at his office on 45th Street. The investigators, meanwhile, had hit her Brooklyn rowhouse. “They’re using very heavy-handed tactics all around,” Aidala told me. The federal subpoena involved fundraising, he said, and the DA’s warrant was related to an investigation of potential bribery. Lewis-Martin assured her lawyer she had done nothing wrong. He moonlights as an AM-radio host, and she appeared on that evening’s edition of his show, “The Arthur Aidala Power Hour.”

“We are imperfect, but we are not thieves,” she said on the air. “And I do believe that in the end, that the New York City public will see that we have not done anything illegal to the magnitude or the scale that requires the federal government and the DA’s office to investigate us.”

The defense was set: Maybe we’re just a little criminal. The indictment alleged that, for years, starting during his tenure as Brooklyn borough president, Adams had cultivated a relationship with a representative of the Turkish government who arranged for him to receive some $123,000 worth of illegal gifts, such as discounted business-class tickets on Turkish Airlines and a stay in the Bentley Suite at the St. Regis in Istanbul. When Adams ran for mayor, his Turkish supporters allegedly channeled illegal donations to his campaign through straw donors with the connivance of Adams himself. In return, prosecutors say, Adams performed a number of favors as a public official, most notably pressuring FDNY inspectors to certify that the new Turkish Consulate near the U.N. was safe without conducting the necessary inspections.

The mayor’s defenders described all this as a whole lot of nothing. His defense attorney, Alex Spiro, ridiculed the indictment, calling it the “airline-upgrade corruption case,” and filed an immediate motion to dismiss the bribery charge, citing a recent Supreme Court decision that enlarged the bounds of acceptable gift taking. (He had less to say about the foreign donations.) Over the following week, Adams went on the offensive, speaking to Black audiences and looking to clothe his plight in the language of redemption.

“I’m not going to resign,” Adams said at Emmanuel Presbyterian Reformed Church in the Bronx the Sunday after his indictment. “I’m going to reign.”

The city’s political class seemed to take a deep, steadying breath. Influential voices in the Black community called for due process. Hochul went quiet. Everyone would wait to see how deep the rot went. Spiro has said he wants a quick trial, which could occur before next year’s Democratic primary. But investigators appear to be taking their time. They are reportedly looking into the mayor’s dealings with other foreign governments in addition to Turkey and scrutinizing contracts for the school system and migrant shelters. More revelations and indictments are sure to be coming.

Not since the dying days of the Koch administration had the city appeared to be so much for sale, and never in the 126 years since the five boroughs consolidated had any mayor been personally charged with crimes of corruption. Adams and his supporters, determined to brazen it out, were convinced that the old rules of political accountability no longer applied. “We look at what happened with President Trump,” said Bishop Gerald Seabrooks, a minister who prayed with Adams at Gracie Mansion the morning the indictment was unsealed. “Thirty-four counts, and nobody is asking him not to run.” (During a press conference, Trump wished Adams luck in his legal fight.) Adams loyalists signaled that if Cuomo, or anyone else, wanted the mayoralty, they would have to take it. “We don’t worry about what’s in the shadows,” said attorney Frank Carone, the mayor’s still-influential former chief of staff. “The mayor is not resigning — full stop.”

With Ingrid Lewis-Martin at a rally of clergy and community leaders outside City Hall on October 1.

Photo: Mark Peterson/Redux

Eric Adams had the talent to be a great mayor. He is as lively as his city and loves its nightlife, even if it brings him into contact with some unsavory characters. He is funny, and there’s a lightness to his egotistical flourishes, like his prodigious use of the possessive case (“my city,” “my cops”) and his practice of walking out to “Empire State of Mind” when performing even the smallest mayoral function, like wheeling the Sanitation Department’s new trash can up to a press conference.

Until recently, Adams’s habits of evasion, of creating a fog of mystery around even the most basic questions — where does he live? What does he eat? — had mostly made him seem like a scamp, not a criminal. Even after his indictment, some of those who had worked for him found it hard to believe he is personally crooked. “I’m certain that Eric is not corrupt,” says a former Adams aide. “On the other hand, Eric can have terrible judgment in people and is incredibly stubborn.” Adams has often called himself “perfectly imperfect,” a phrase that now seems likely to serve as his epitaph, however the end comes. The positive side of his record includes his hiring of a number of highly competent — and mostly female — deputies and empowering them to run much of the city with minimal interference. The imperfections start with some of the other individuals on his payroll, who represent the very worst that city politics has to offer.

“How did we get here? He brought with him a set of people whose track record of corrupt activity was already well known,” says Brad Lander, the city comptroller and a declared candidate for mayor in the next election. “I think that sent a broad signal to people that this was an administration with a very high tolerance for corruption. And unfortunately, a lot of people seem to have gotten that message and then people who did really genuinely try to do things with integrity paid for it.”

Reports of corruption have dogged Adams’s administration since its earliest days; now, they’re just more detailed. Straw donations. A nightclub-shakedown racket. Nepotism hires. A buildings commissioner who took alleged bribes from alleged mobsters. A mayoral crony who supposedly cried out, “Where are my crumbs?” And it was all so crummy, so careless, so old-school, so Tammany Hall.

“It’s a surprise to me how stupid they seem to be,” says one veteran of Brooklyn politics who has seen a few bosses come and go. “In the sense that if you’re going to milk your positions for private gain, that they weren’t more thoughtful about how they went about doing it.”

Adams never tires of talking about his days as a cop on the beat, and he is fundamentally a creature of the NYPD and its clannish patronage culture. He was swept into office as the law-and-order candidate, accompanied by a bunch of friends from his days in the department, including Lewis-Martin, who was married to his former Police Academy classmate, and Phil Banks, a family friend whom he appointed deputy mayor for public safety despite his being cited as an unindicted co-conspirator in a previous corruption case. David Banks, Phil’s brother, was put in charge of the Department of Education, and Sheena Wright, David’s partner, was appointed Adams’s first deputy mayor. Adams tried to appoint his own brother, Bernard, a retired cop, to be the executive director of the mayor’s security at a salary of around $210,000. (After news reports and objections from the city’s Conflicts of Interest Board, Bernard was given a $1-a-year role as a “senior adviser,” and he has since left the government.) The mayor’s girlfriend, Tracey Collins, has a high-paying job as an adviser to deputy schools chancellor Melissa Aviles-Ramos, who was recently tapped to take over for David Banks.

No appointee exemplified the Adams approach to government better than Tim Pearson, a former police inspector and 9/11 hero who acted as a sort of minister without portfolio. “When Eric wanted something done by someone that he trusts,” says the former Adams aide, “Pearson got dispatched.”

For a while, Pearson was working simultaneously for the mayor and Resorts World New York City, the company that runs a casino at the Aqueduct Racetrack. (During Adams’s tenure as a state senator, which ended in 2013, a report by New York’s inspector general rapped him for ethical improprieties related to the casino’s licensing deal.) Adams publicly called Pearson one of his “knights of the Round Table” and assigned him to deal with such issues as the migrant crisis. Pearson led a city delegation to the Mexican border and played a role in shelter contracting, meeting almost daily with Molly Schaeffer, the city official in charge of programs for asylum seekers. Schaeffer was recently subpoenaed to appear before a grand jury.

Pearson and Phil Banks worked side by side in the Verizon Building, an intimidating concrete-slab skyscraper on Pearl Street. It was there that Pearson reportedly stalked around the office demanding “my crumbs,” earning him his workplace nickname — Crumbs. According to three workplace-discrimination lawsuits filed by former police officers, Pearson talked openly in the office about wanting a personal cut of shelter contracts. (He has denied the allegations in the lawsuits, which are ongoing.) The lawsuits also claim that Pearson and Phil Banks approved discretionary promotions within the Police Department and that Pearson used his position to pressure women for sexual favors. When one of the plaintiffs, a sergeant assigned to a newly formed city-government inspectorate called the Municipal Services Assessment unit, refused his advances, Pearson allegedly blocked her promised promotion. When her colleagues complained, they claim they were demoted. For months after the lawsuits were filed, Adams defended Pearson. He stuck with him after he allegedly got into a fistfight with private security guards at a migrant shelter, and after the New York Times reported he had visited the guards when they were detained at a police station and threatened them with retaliation, and after his phone was seized by federal investigators. At a September 17 press conference, Adams claimed his friend had “saved hundreds of millions of dollars by bringing down the costs” in contracts.

That was well after the Feds, in an overwhelming show of investigative force, had served search warrants to Pearson and several others in the mayor’s orbit. Agents visited the home that David Banks shares with Wright, reportedly looking into dealings he and Phil had with a third brother, Terence, a former MTA employee who set up a side business as a consultant to companies seeking city-government contracts. (Ben Brafman, an attorney for Phil Banks, tells me the prosecutors were looking into Zelle payments between the brothers, which he said were actually used to settle poker debts and had “nothing to do with their respective city jobs.”) Simultaneously, the FBI hit NYPD commissioner Edward Caban, a family friend of Adams’s, reportedly in pursuit of evidence regarding his ex-cop twin brother, who sold his “consulting” services to the nightlife industry. (James Caban, who resembles his commissioner brother right down to his matching goatee, was reportedly chauffeured around the city in an NYPD vehicle; at least one bar owner has accused him of extortion. Both Caban brothers deny any wrongdoing.) These newly disclosed investigations joined a number that were previously known, including a separate probe by federal prosecutors in Brooklyn of Winnie Greco, the mayor’s director of Asian affairs, whose pattern of questionable business dealings was revealed by the nonprofit news organization The City. (One can’t-make-it-up detail: She was reported to have lived rent free for months in a Queens hotel room the government was using as a shelter for the formerly incarcerated. A lawyer for Greco claimed she paid for the room.)

Under Adams, the usual divide in city government between the technocrats and the political hacks has grown as wide and salty as the East River. “There is this really small world of very close people around him that’s its own sort of shadow thing,” says a consultant who knows his way around City Hall. And then there is the Cabinet, made up of those capable deputy mayors Adams has entrusted to actually run the municipal government. Even as the administration has appeared ready to collapse, much of Adams’s governing apparatus is still functioning. “There is some strong talent there despite some of the crazy swirling around,” says a senior city official. The innovative Sanitation commissioner Jessica Tisch’s garbage trucks are still making their rounds. Deputy Mayor Maria Torres-Springer is still overseeing an ambitious development agenda, including the mayor’s “Get Stuff Built” housing-construction program, and his “City of Yes” rezoning initiative. The Economic Development Corporation is still advancing long-term redevelopment projects in places like Willets Point and the Red Hook waterfront.

But the crazy has a way of infiltrating the work. “People are profoundly demoralized,” says Councilmember Lincoln Restler, an Adams critic who previously worked in the city government under Mayor Bill de Blasio. The technocratic part of government can run under its own power for a while, but it will eventually need executive leadership — and an emergency can happen at any time. Can the Fire Department handle a hurricane? Can the NYPD deal with widespread protests? No one will know how prepared the government is for the unforeseen until it happens.

Officials operating a couple of rungs below City Hall, at salaries far beneath what they could be making in the private sector, have to deal with stringent ethics rules. Learning of their bosses’ flagrant behavior, they are watching as slack-jawed as everyone else. “Everybody is really nervous, everybody doesn’t know what’s going to happen next, everybody’s really pissed off,” says one manager at a city agency who oversees millions of dollars in contracting. “There are so many people with integrity in city government, and shit like this is so offensive.” An NYPD official says, “There’s a level of unprofessionalism that is now permeating the Police Department … I’ve never seen it this bad, and it’s beyond upsetting to me. They have made this job a disgrace.”

Like the cop he once was, Adams has been trying to move the political crowd along: Nothing to see here, folks. The morning the indictment came down, Adams was hunkered in Gracie Mansion with Carone and his other lawyers. “In a strange, weird way, there was a sense of relief because the anxiety of the unknown was gone,” Carone says. “There was nothing that the lawyers were not prepared for.” Adams has met the crisis with his usual aphoristic bluster. “I’m not stepping down,” he said. “I’m stepping up.”

Once he gets past the denial stage, though, he will face a menu of unappetizing choices. His current course — fighting the charges while running for reelection — is likely to end in defeat, humiliation, and maybe prison time. If the Supreme Court doesn’t save him, he could hope for a pardon from a reelected President Trump. (It is not hard to imagine Adams, who has criticized the Biden administration’s border policies, taking a Rod Blagojevich role in Trump’s Rat Pack.) But that scenario lies at the end of a draining legal battle.

Resigning might buy him some relief from his legal pressure: Although the prosecutors of SDNY say they are above politics, they can sometimes be placated by a sacrifice. If he gives up his office, however, Adams will lose not just his power but his ability to raise campaign money. Few people who know him imagine he would go voluntarily.

There are two legal mechanisms for the removal of a mayor, neither of which has ever been employed successfully. The more convoluted one, contained in the city charter, gives an “inability committee” made up of city officials the power to remove him. But the mayor has a hand in appointing two of its five members and an ouster requires four votes, so that would appear to be a nonstarter. The more straightforward route runs through the office of the governor. On paper, Hochul possesses a nearly unchecked authority to suspend Adams and then, after a proceeding allowing him a chance to defend himself against her charges, strip him of his office. There is a reason, though, that no governor has tried anything like that since the days of FDR. Hochul has to think about her own reelection, and she cannot afford to alienate any Democratic constituency. “Really, to me, the governor only makes this call if the governor has the consent of the Black political class,” says one state assemblymember from New York City.

In the days after Adams’s indictment, the rest of the city’s leadership waited for definitive statements from people like Attorney General Tish James, House Minority Leader Hakeem Jeffries, and, most of all, the Reverend Al Sharpton, who holds no office but is nonetheless viewed as one of the people who could have the final word on Adams’s political fate. The day Adams was arraigned at federal court in lower Manhattan, Sharpton said he was withholding judgment. “We’re going to see where the evidence is,” he said at a rally for his civil-rights group, “but we are not going to stand by silently and let Governor Hochul not know that some of us are saying, ‘Do not change the process and the precedent.’”

Soon, others would converge on a similar position. Jeffries said Adams should not resign but still needed to articulate “a plan and a path forward.”

Sharpton told me he had talked to both Adams and Hochul about the situation and said, “I think that, at the end of the day, the governor will make the right decision” and allow the mayor to be “given his day in court.” But his support is far from unconditional. “The city has to be run right,” Sharpton said, and he added that if Adams came to feel he was too distracted to continue doing his job, “he should consider stepping down, and I think he would, and I think some of us would urge him to do so. But that is his decision.” Sharpton left open the possibility that future revelations could cause him to change his position. “I don’t know where this investigation is going,” he said. “It would be silly to do that, to lock myself in.”

Like everyone, Sharpton is now waiting to learn what else SDNY may have on Adams and the other members of his circle. On the morning of the indictment, Williams stood next to a placard on an easel listing the mayor’s alleged bribes and described what he called “a grave breach of the public’s trust.” He took no questions. Afterward, security rushed the press past a conference room where the prosecutors who had stood behind him could be glimpsed cracking nervously celebratory smiles. But nothing was finished.

Given the sheer number of investigations reported to be underway, many potential paths are open to prosecutors. The Turkey indictment left unclear the status of Brianna Suggs, the 26-year-old former Adams campaign fundraiser — and Lewis-Martin’s goddaughter — whose house was searched in November. According to the indictment, Suggs called Adams five times as the raid was ongoing, and the mayor, who was on his way to a meeting at the White House, ordered his plane to turn around and fly back to New York. Suggs is now presumably under intense pressure to cooperate with prosecutors, if she is not yet doing so. (Her attorney did not return calls.)

Other Adams confidants, like the Banks brothers and Pearson, may also possess information that would make them valuable witnesses if they were to flip. And prosecutors have digital evidence they have yet to review. They disclosed last week that the FBI has still not been able to access the mayor’s personal phone, which it confiscated in November. Adams changed the six-digit pass code shortly before the Feds got it — he told investigators it was to “prevent members of his staff from inadvertently or intentionally deleting the contents” — and claims to have forgotten the new code. Eventually, the FBI should be able to crack it.

Hochul has reportedly given Adams an ultimatum demanding personnel changes. The week after the mayor’s indictment, Pearson submitted his resignation, and news broke that Wright is leaving too. The date of David Banks’s retirement as schools chancellor, originally scheduled for the end of the year, was pushed up to October 16.

Hochul and the state’s other Democratic leaders, however, have practical reasons to give Adams more time. If he were to go too early, Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, a champion of the democratic-socialist movement, would become acting mayor, giving the left a foothold in City Hall. And if the mayor’s office is vacant, the law calls for a citywide election within 80 days — a seemingly ideal scenario for a candidate with a lot of money and name recognition, like Cuomo.

The former governor is already laying the groundwork for a campaign, reaching out to old allies and contacts in the city’s business and political communities. “I was on the phone with Andrew Cuomo 20 minutes ago,” one insider told me. “I think it’s highly, highly likely that he runs” if there is a special election. This has created a strategic bind for the Democrats who have said or signaled they plan to run, including Lander, former comptroller Scott Stringer, and state legislators Zellnor Myrie, Jessica Ramos, and Zohran Mamdani. They had been planning to run against an unpopular incumbent in a Democratic primary, not against Cuomo in an open election.

“I am not afraid of Andrew Cuomo,” Ramos told me. “I think there is plenty to be said about how we are the greatest city in the world, and somehow we have to rely on a revolving door of scandal-marred men.” But Cuomo’s entry would scramble the field and perhaps draw in other heavyweight challengers, like Tish James, who is said to be listening to appeals to enter the race.

And then there is Adams, who still says he is running. A poll released by Marist College on October 4 found that 69 percent of city residents wanted Adams to step down, and a similar number said Hochul should remove him if he declines to go willingly. (A majority opposed a potential Cuomo bid, giving heart to other Democratic challengers.) Those numbers would appear to spell doom, but Adams is making the calculation that if he stalls long enough, maybe the scandals will wane in importance to voters, the way Trump’s indictments and felony convictions have shrunk to near irrelevance. Maybe then he can convince New Yorkers that his favor-trading, crony-protecting, luxury-pursuing ways are just politics as it is and has always been.

“Everybody takes upgrades,” Powell told me on October 1 as he milled around outside City Hall, waiting to participate in a rally in support of the mayor. “We feel this is a total overreach and the truth will come to light.” A group representing the core of the Adams coalition — religious leaders, the Black police organization the Guardians, and political operators like Powell, the inheritor of a famous Harlem name — assembled on the building’s steps. Some held signs that read WE ❤️ ERIC and WE STILL BELIEVE. Someone started singing a gospel song, and a procession of speakers came forward to testify for the embattled mayor.

“It’s a wonderful thing when everything is going well and people are cheering your name. It’s another thing when they’re screaming ‘Crucify him,’” said Bishop Dr. Chantel Wright. “We have his back, and we stand today to make that declaration, and we say, ‘As long as we stand, nobody is going to hang him prematurely.’” Adams appeared at the top of the stairs dressed in a charcoal suit and an open-necked white shirt with French cuffs, beaded bracelets jangling on his wrist and a neatly folded handkerchief in his breast pocket. He forded down the steps, through the crowd, following Lewis-Martin, who was wearing a hot-pink blouse and a large cross.

“This administration is about helping those who were not given the help that they needed for so long,” Adams said. “People are going to try to distort the moment.” He mentioned speculation that he was asking for Trump’s help. It wasn’t true, he implied: “I got lawyers.”

The crowd shouted “noooooooo” when he mentioned some people were calling for him to step down, and when he suggested that “the loudest are not the majority,” someone called out, “Say it!” Then Bishop Wright offered a three-minute blessing in preparation for an upcoming preliminary hearing. “Father, as he goes into the courtroom even on tomorrow, water the mouths of the lawyers, water the mouths of those who will stand on his side,” she prayed. “And heavenly Father, for those who have set up traps, Father God, we pray that they slip and fall in them themselves.” Adams and Lewis-Martin stood with their heads bowed and eyes closed, their hands clasped tightly, still in it together.

Source link