(RNS) — The new movie “Between the Temples,” billed as a black comedy, gets the comedy right — there are plenty of laughs along the way — while the “black” part comes with the movie’s examination of the completely destabilizing nature of grief. “Between the Temples” follows the supposed resurrection of Ben, a cantor at a synagogue in upstate New York, whose wife died a year before. After visiting a congregant who has had a stroke, Ben is asked whether he ever feels like his brain is having a heart attack, and he responds, “All the time.”

Under the spell of grief, Ben abandons his duties at the bimah, makes awkward small talk with the women his two moms set him up on dates with, falls down while running drunkenly and gets into fights in bars when his fellow drinkers make fun of him.

But Ben’s bigger problem is that grief has robbed him of his voice. He can’t, or won’t, sing, his primary job responsibility. As he tries to put his life back together, he runs into his old grade school music teacher, Carla, and she takes him on a journey of redemption, asking him to prepare her for the bat mitzvah she never had.

The heart of the movie is the music, especially the cantillation — the ritual chanting of prayers or Torah portions in the Jewish tradition — that truly elevates the emotional quality of the film. Music is also a metaphor for Ben, who finds that in life we each get to craft our own song, even if it is, as he puts it, “messy” or “sloppy.” We should follow our hearts, wherever our life-song leads.

That would be an easy message to take from the film, but for Ben, the results are fairly catastrophic. He engages in an affair with someone he has direct authority over, puts his job in jeopardy and crosses boundaries that left me, a clergyperson, aghast. The message I took from watching the slow-motion trainwreck of Ben’s affair is how porous boundaries — in work, in love — put everyone in danger, clergy like Ben included.

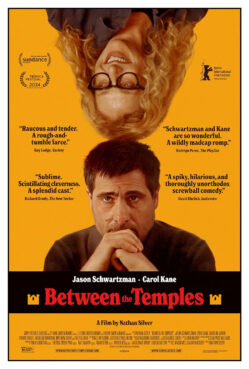

“Between the Temples” film poster. (Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics)

One character sneers at Ben that he has no interest in organized religion, and it’s hard not to take the critique seriously, given the mess that Ben makes not only with his own life, but in his religious community.

Everyone deserves space to process their grief and to even make a mess of things, clergy included, but that grace has to be tempered with the realization of the power dynamics within a congregation, where the spiritual leaders have immense authority. Thirteen states and the District of Columbia make it a crime for clergy to engage in sexual misconduct with adults in the community they serve.

We as a culture don’t seem to be able to reckon with this truth. The story of the more than 5,000 Roman Catholic priests accused of sexual abuse hardly need further press, but it’s worth noting that at least 1,700 of them continue to live and work in a variety of roles in the community where the abuse occurred, according to a 2019 report from the Associate Press. A previously secret 2022 report released by the Southern Baptist Convention detailed some 700 instances of abuse, yet the Baptists are still sorting out how they plan to prevent more.

Jewish communities are not immune. The Conservative movement recently released a list of clergy ejected or suspended by the Conservative Rabbinical Council for a variety of reasons, including sexual abuse. Likewise, in 2021, a Reform rabbinical school, Hebrew Union College, released a report that detailed 50 years of abuse from former professors.

In such a context, it is hard to view Ben’s resolution of his problems at the end of “Between the Temples” as a heartwarming tale. Ben certainly charts his own path, but the destruction he leaves in his wake are no mere joke, dark or otherwise. There are tears, yelling and immense pain wrought by his actions, as there often is when clergy do what they like.

Robert Smigel as Rabbi Bruce, left, and Jason Schwartzman as Ben Gottlieb in “Between the Temples.” (Image by Sean Price Williams. Courtesy of Sony Pictures Classics)

So yes, there are some real lessons to be learned in “Between the Temples,” but I’m not sure they are entirely what the filmmakers intended. Religious leaders must keep ever before them the fact that how they behave and even process their grief has a direct impact on those in the communities they serve. That is the central fact that they have to keep between their temples.

(The Rev. Michael Woolf is senior minister of Lake Street Church of Evanston, Illinois, and co-associate regional minister for white and multicultural churches at the American Baptist Churches of Metro Chicago. He is the author of “Sanctuary and Subjectivity: Thinking Theologically About Whiteness and Sanctuary Movements.” The views expressed in this commentary do not necessarily reflect those of Religion News Service.)

Source link