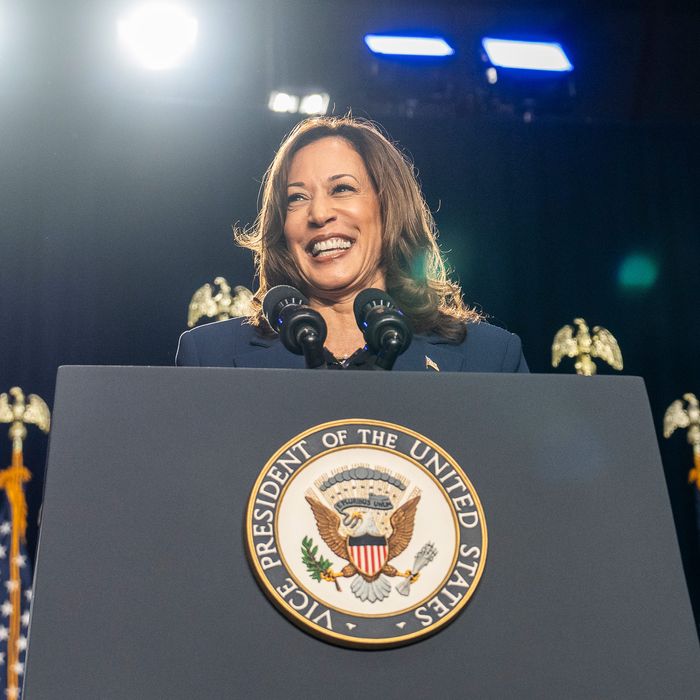

Photo: The Washington Post/The Washington Post via Getty Im

I was in a movie theater on Sunday afternoon, watching Inside Out 2 with my kids, when my phone began to vibrate with the news that Joe Biden was stepping down and, soon after, that Kamala Harris would almost certainly be the Democratic nominee. I sat in the cool dark room and tried to take in what was happening simultaneously on the screen in front of me and the brain inside of me: Anxiety, the emotion whose stated aim in the movie is to protect the heroine “from the scary stuff she can’t see,” and to “plan for the future,” since “the next three days could determine the next four years of our lives!” was producing a whirling, spiraling cloud of fear about how much was at stake and all the ways it could go wrong.

The texts and WhatsApps were coming in fast, swirling round me until they formed their own panicked tornado: I’m so excited and so afraid she can’t win. The racism, the sexism, the racism! The polls are iffy. This nation is not evolved enough for this. I am so scared. Can we even do this?

None of us knows if we can do this. And we are about to do it anyway. And the combination of those truths helped me, in those vertiginous few minutes, to not feel panic but excitement. I felt excited about the future for the first time in years.

More than that: I felt excited not in spite of my uncertainty, but because of it. I felt that our national political narrative was finally accurately mirroring our national reality: Everything is scary, we have never been here before, we don’t know if we can do this, and precisely because these stakes are so high, we are at last going to act like it, by taking unprecedented, untested, underpolled, creative measures to change, grow, and fight at a pitch that meets the gravity of the urgent, existentially important task in front of us. No more clinging to the walls of the past for safety, no more adhering to models or traditions or assumptions that the autocratic opposition has shown itself willing to explode over the past two decades in its own efforts to win.

Our aversion to uncertainty is part of how we got to this precipice. Too unwilling to take risks — on people, ideas, and platforms, on the next generation of leadership — Democrats have remained chained to the past.

We have just been through weeks of wrangling over Biden, a man whose administration exists in the first place because of assumptions that he would be safe and familiar, the kind of person we know to be electable, because we have elected so many like him. We only broke from him because our vendors of certainty — the polls, the self-assured pundits — suddenly went wobbly. These are the very people who made Biden president to begin with in 2020, landing on him as the most secure, stable object in a primary field studded with riskier (and more potentially thrilling) candidates like Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren, and Harris herself — candidates who had been different from what came before, and had thus been understood as too dangerous.

Biden was not different from what came before; he was what came before, in the White House and in the Senate for nearly 50 years. He has since steered us through a period in which so much that was novel, without modern political parallel, has been real bad: from viruses to armed insurrection to the rollback of established rights to the deification of Trump and the threat of his return. It is correct to feel terror, to apprehend that what many took to be the solid ground beneath their feet is shaking.

But the reaction to that instability cannot be simply cleaving to an old order, or we will never make new precedent that is good, that is innovative, that is groundbreaking and exciting.

We are now in the position of perhaps doing so many things that this country has never been able to do before: elect as president a woman, a Black woman, an Indian American, a person born in 1964 — and we are trying to do it in less than four months. Each of these things would be historically anomalous and, in this case, extremely salubrious for our republic, an improvement and expansion on what has previously been possible, a repudiation of so much that has long been waved off as impossible.

There are certainly terrible things in store: the racism and sexism Harris will face, the monstrous and vengeful resistance to her rise, in which she will be accused of incompetence and radicalism and being an affirmative-action token and a barren cat lady and a welfare queen who has slept her way to the top, all according to the right’s overfamiliar playbooks for how to discredit people they would rather not participate fully in this democracy and helped by a media happy to engage in double standards. We know there will be bad polls and gaffes. And those who feel scared about what is on the line, including possibly me, will be tempted to say, “I told you this would happen!” because in our moments of direst discomfort we take slim consolation in certainty, even when the certainty is about how awful we knew everything was going to be.

But if we permitted that dismal comfort to guide us, we would not have any space to be shocked and inspired by how good some things can be: the giddy memes emerging from an improbably enthused online left, the cheerily halved “BIDEN/HARRIS” yard signs now reading simply “HARRIS.” The $81 million in donations raised in 24 hours. The 58,000 volunteers who stepped up in less than two days to work phones and knock doors. The Sunday-night zoom call hosted by Win With Black Women and Jotaka Eaddy, which was scheduled to accommodate 1,000 women, that eventually had to make room for 44,000 participants, all within hours of Harris becoming the unofficial candidate. The next night, a call organized by Win With Black Men drew 53,000 registrants, well above its capacity, of whom 21,000 were ultimately able to attend.

This is part of what uncertainty can bring: surprise, innovation, collaboration, spontaneity. Things we don’t expect. Which feels like a particularly important revelation after weeks of hand-wringing about dismal historical precedents. Throughout the tormented weeks in July during which Biden’s fate was the pressing question, we heard so much about 1968, an election year that had already been top of mind because of student protests and a Democratic convention in Chicago. But it hit a fever pitch as Democrats argued over whether to stick with an increasingly unpopular leader, recalling that Lyndon B. Johnson’s withdrawal 56 years ago culminated in a grievous loss at the polls.

But, as someone who frequently uses history as a lens through which to better understand our present, I will submit that its lessons are simply not always directly mappable onto either present or future. Each time I’ve heard a warning about 1968, I have remembered similar warnings through all of 2008 about another bad election year for Democrats, 1972.

After the swell of youth enthusiasm for Barack Obama’s primary run, historians and journalists gravely shook their heads, reminding younger Americans of how, back when the kids pushed so hard for George McGovern to win his party’s nomination, they did not come out in numbers large enough to win him the presidency. It was true that that generation of young people did not show up at the polls for McGovern. And then it was true that young people did come out in record numbers for Barack Obama.

That year, we were also repeatedly warned of the intraparty acrimony that followed Ted Kennedy’s primary challenge and helped to doom Jimmy Carter’s 1980 bid for reelection, leaving us with Reagan and his terrible legacy. The extended, bruising primary between Obama and Hillary Clinton in 2008 was supposed to leave the same bitter taste, and yet what that rancorous period wound up doing was engaging the whole nation and ultimately uniting the Democrats behind a candidate who pledged to turn the page on the awfulness of the Bush years. It helped create an electoral infrastructure that became Obama’s historic campaign.

I do not want to lean too heavily on memories of 2008 for their own false comforts. This is a different time, a different candidate, and our national circumstances have changed. But the fact that we are in unfamiliar terrain should be welcomed as great news, especially after years in which the Democratic Party has repeatedly defied expectations born of past certainties: In 2018, record numbers of young candidates won, many of them running as first-time candidates and with left-leaning agendas, even as polls predicted their losses in the days before Election Day. Since the Dobbs decision, Democrats have surpassed expectations in nearly every single election, in part by communicating about the loss of abortion access in ways that generations of advisers warned them were imprudent. After decades of treating the issue as something quiet and shameful, something about which “pro-choice” politicians had to be stoic and a little sad, a post-Dobbs movement to embrace abortion access full-throatedly as a core American value secured Democrats wholly unpredictable wins. Harris has herself been among the leaders of this unconventional communicative charge.

The idea that this election represents a tipping point for American democracy is so widely accepted that it verges on cliché. And yet precisely because of the way in which this explosive, breakable thing has been, until now, wrapped in tissue paper, the presidential campaign has also been, to too many voters, incredibly boring and demoralizing.

Which makes no sense, and should on its own be an indictment of the old and purportedly safe approach to Democratic politics. How can you convince people that we are in an emergency when what you produce to fight the fire is overfamiliar, dull, flat? If it were consequential, surely the party would have brought its best, would have lit up the sky with energy and fury, to meet the moment and grab the nation’s attention.

Now, the big risks of a short election season with a new candidate makes it all make sense. We do not have all the graphs and charts and stories about the 1960s to reassure us that we can win. And this reality telegraphs far better than any “safe” choice would: that this is an emergency, a six-alarm fire, so close to burning us to the ground that we are acting as we never have before. This is the opposite of boring.

And the opposite of boring is what the liberal-left project should stand for. Even as the Republican Party breaks the very institutions of democracy, it sells itself as a nostalgia act, disposed to keeping things as they are and more alarmingly, returning them to what they used to be.

The left’s communicative project has always been thornier, since the world it is fighting for is made up of possibilities that have not yet ever been fully realized — not a return to the past but an imaginative leap forward to a better and more equal world. It should be a more joyful and energetic project but has too often been harder to sell, because it requires believing in something we have never been able to see or call back to, that we don’t remember, that is harder to make neat or pithy or put on a hat.

Perhaps this is why so many Democrats have clung to the rocks of a familiar path instead of looking out over the cliff and imagining a long, scary jump toward an unknown shore. What if they fell and lost everything? And with the most vulnerable — the people the party, at its best, wants to represent, empower and protect — most at risk, this caution has been rational, even moral.

But look. We have now lost so much already and are on the verge of losing so much more. There aren’t many rocks left to cling to, and the ones that exist seem to have cognitive impairment and COVID. So we better leap. We have to leap!

Source link