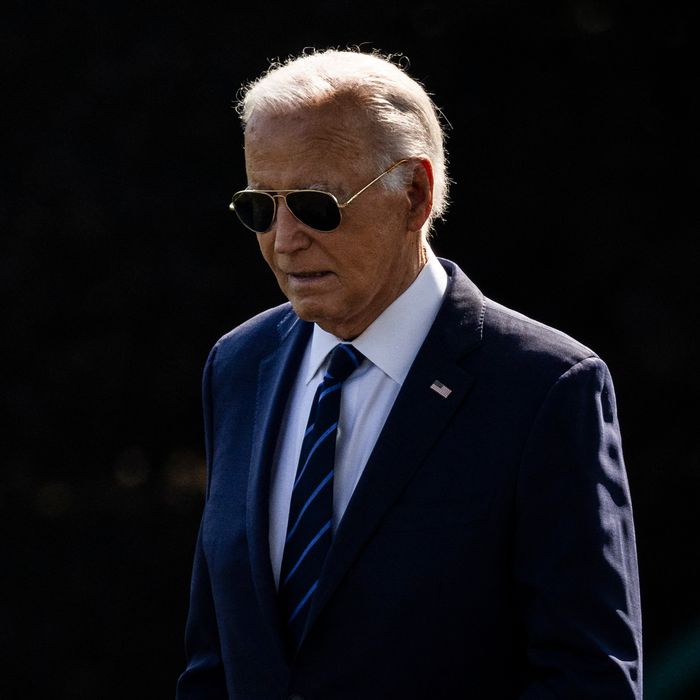

Photo: Samuel Corum/AFP via Getty Images

In the end, it was Joe Biden who accidentally toppled his own campaign. It was the president’s own insistence on an earlier-than-ever debate against Donald Trump that exposed the true extent of his aging and kick-started his own party’s dramatic and unprecedented campaign to remove him from the ticket.

And it was his demand on running again in the first place, dismissing even the supporters who worried the 81-year-old wouldn’t be up to it, that has left his presidential legacy in a precarious place. His time in office may now be remembered as a greatly consequential and progress-driving term led by the man who once served as the vice-president to Barack Obama, the first Black president, and who chose Kamala Harris, the first woman vice-president. Or it could go down in history as a briefly hopeful intermission between two dark Trump terms that could reshape the country.

The ultimate tragedy of Biden’s presidency is that time caught up with him and that he didn’t realize it sooner, even if his decision reflects a concession to reality. It’s a sad denouement to an unlikely political career of over 50 years and for a sympathetic man with a devastating life story and a winding rise from local Delaware politics, up and through the U.S. Senate, to the vice-presidency and ultimately the job he wanted most for decades, the presidency.

Biden’s decision to drop his reelection bid on Sunday was primarily about giving the country a legitimate chance at a non-Trumpian future. In the letter announcing his decision, he wrote of rescuing the country from the pandemic and economic crisis and protecting democracy. He was stepping aside, he said, for the sake of the nation, underscoring the gravity of the moment. It is plainly his hope he will be remembered fondly for his work in office and before — or, in terms dear to him, that he will be remembered as a defender of democracy and liberal values who bolstered that credential by stepping aside. That’s better than the alternative: that, running a race he could not win because he took too long to realize his own limitations, he might have unwittingly become complicit in the nation’s fall into authoritarianism.

It was a cruel fact of politics that he only attained the presidency amid a global pandemic, after a world-reordering administration premised on the power of division. And it’s an even harsher one that his own promises to move the country beyond the age of his predecessor will be the standard by which he is ultimately judged.

As president, Biden operated the only way he knew from his half-century in office: by working alliances on Capitol Hill and across the globe, sometimes to great effect. It was always possible to read his view of the presidency — focused on maintaining a liberal international order and passing as much legislation as possible — as a mismatch to this moment in American history. In an era when the country has come to expect its presidents to represent big ideas about the nation’s self-conception and to transcend politics (for better or for worse, to act as national arsonists or preachers), his more mechanical approach sometimes felt like it belonged an earlier time, maybe one of the previous decades in which he’d pursued the White House.

Yet this read might be uncharitable to Biden and the limits of what any politician could realistically do in such a historically volatile moment. For one thing, he accomplished the initial goal of his presidency the moment he took office after a violent insurrection: He removed Trump from the White House. This view also undersells the administration’s success based on its own stated goals. Many of his accomplishments — say, investments in infrastructure and microchip manufacturing — will likely be remembered far differently once their effects are felt, years down the line. And it’s been clear since even before his approval rating started to dip in his first year in office that he had history on his mind. His granddaughter summed up the family’s thinking in a social-media post just after he left the race, calling him “the most effective president of our lifetime” who had “likely already cemented himself as the most effective and impactful public servant in our nation’s history.”

Familial overexuberance aside, there is already a case to be made for a historic legacy considering the short and dramatic window he had to accomplish much of it, before Republicans with no interest in compromising took over the House in 2022. He has perhaps done himself a disservice by comparing himself to Franklin Roosevelt and Lyndon Johnson, but his most productive years will still be remembered for wrangling major liberal legislation on social, economic, and safety fronts: massive pandemic relief after a singular catastrophe, significant climate and infrastructure investment, and even some marginal bipartisan gun-control measures while dealing with a pair of senators from his own party who were often eager to moderate his ambitions.

His maneuvers on lowering drug pricing are beginning to be felt, and his move to nominate Justice Ketanji Brown Jackson, as well as a slate of diverse judicial and federal officials, will resonate for years to come, as will his repeated support of labor unions. Internationally, he may yet point to bolstering NATO and aiding Ukraine against a Russian invasion as his greatest accomplishments.

Yet it was a leftover goal from his time as vice-president that sowed the end of his legislative productivity and certainly his popularity. Still feeling as if his failure to convince Obama to end the war in Afghanistan was a missed opportunity during their administration, his insistence on pulling out troops in August 2021 led to a disastrous extraction. Elite opinion and Washington sentiment turned against him, while Republican critics who’d previously struggled to find a compelling line of attack on him felt empowered and began painting him as incompetent. As his approval rating began to dive, other cracks emerged in politically vulnerable places, hastening his descent into Jimmy Carter–like, then Trump-like, numbers: a surge of illegal immigration, painful inflation, and, by late 2023, Israel’s devastating war in Gaza waged largely with his support that split Democratic opinion on him.

Meanwhile, he was unable to safeguard some of the policy moves he intended to have immediate impact from partisanship and skeptical courts. A dive in the child-poverty rate as a result of his initial COVID recovery package was short-lived when his allies couldn’t find support for reupping the investment in Congress. His student-loan debt-relief measures were repeatedly struck down by unimpressed judges.

Yet having campaigned on moving the country past Trump and to a new, calmer normal, he paid perhaps his largest political price for failing to slow the growth of profound rifts in American society — possibly an impossible task for any one president, especially in the age of Trumpism, but nonetheless a popular knock on him that coincided with spiraling price rises. All of it led many to believe the country was going in the wrong direction for much of his last three years. The fall of Roe v. Wade at the hands of a conservative Supreme Court added to the sense of malaise on the center and left.

Still, having a long list of popular achievements bolstered his sense of accomplishment, and Democratic overperformance in the 2022 midterms, which were often predicted to be a Republican romp, fed a sense of vindication. As he saw it, voters wished to reject right-wing extremism and embrace his message about defending democracy. So it was an immense frustration to him that widespread doubt remained about whether he would run for reelection, which he felt was his inherent right as an incumbent president and a successful one at that.

As 2024 approached, Biden was continuously befuddled and offended by the belief that he would only serve one term, and he largely refused to seriously consider his political vulnerabilities, such as his age. He was convinced that as the only Democrat to have ever beaten Trump, he should be the one to try again. Yet Biden was visibly slowing down physically, even as those around him always insisted his mind was as sharp as ever. And as the questions persisted despite his insistence that he would run again, he began to grow feistier behind the scenes about so-called allies who weren’t defending him enough and who didn’t appreciate his long list of wins.

He proved an unconvincing campaigner at 80 and 81, and persistent high prices and surges at the border kept his approval ratings low as he struggled in a race against his resurgent predecessor. His contention that he would regain the lead once voters refocused on Trump and his unacceptable behavior proved insufficient, as much of the electorate — especially his target voters — stayed tuned out even deep into the election year. It was ultimately his own bravado that did him in politically: challenging Trump to a debate that he was sure he would win and use to expose the Republican as an extreme, incoherent, and unfit convicted felon. Biden thought he was setting himself on a clear path to a second term. Instead, the furious national focus swung to an enfeebled president who struggled to get through sentences.

The ensuing weeks were as painful for Biden’s party as any since Trump first won the presidency, as the president doubled down, retreating into a smaller inner circle of aides than ever and suspecting former friends like Obama and Nancy Pelosi of organizing against him. As his campaign’s money fountain started to dry up and more party officials demanded he leave the ticket, Biden couldn’t believe his objectively voluminous record as president and all the goodwill he’d earned in the Senate and vice-presidency weren’t resonating with his party. He insisted only “the Almighty” or his doctors could convince him to depart.

Only when it was obvious to him that he could no longer win a second term did Biden begrudgingly step aside as the Democratic nominee, still in some measure of disbelief that the political system he’d spent over half a century trying to master had so quickly turned against him. His first White House chief of staff, Ron Klain, accused “the donors and electeds” of “push[ing] out the only candidate who has ever beaten Trump,” implicitly channeling Biden’s own sense of exasperation.

It was a bitter irony that none of this would likely have occurred had Biden not challenged Trump to the early debate, before the Democratic Party had a chance to formalize his place on the ticket at its convention.

One week before Biden ended his candidacy, while rumors swirled about party leaders organizing to force him out of the race, he postponed a scheduled trip to the Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library in Austin. His visit was supposed to commemorate the Civil Rights Act, and he postponed it because of the assassination attempt on Trump. But it was an auspicious destination and postponement, considering the circumstances.

Biden has often quietly compared himself to LBJ — a longtime Hill operator brought into the executive office by a younger, more charismatic liberal hero president with whom he had a complicated relationship. Johnson then became a consequential president remembered for his wide-reaching social legislation in a time of extreme national strife. But the comparisons tended to end there, just short of Johnson’s decision not to seek reelection early in 1968 with the unpopular war in Vietnam dragging on. Biden always hated the notion that he might even consider following Johnson’s lead but now will likely take solace in the idea that history may find the comparison between the two to not, in fact, be as ridiculous as some of Biden’s critics had long contended.

Yet there’s no escaping the fact that while Biden’s presidency may be defined by his accomplishments and perhaps his ultimate elevation of the first woman president, it is also possible that his time in the White House may still be defined by Trump. If the 45th president becomes the 47th, he may set out to erase all of Biden’s record and possibly that of Obama and every Democratic president since Johnson.

As such, much of Biden’s legacy is now up to the voters, specifically in the form of their support for Harris, the likely Democratic nominee whom Biden hired from the Senate but did not always set up for success throughout his administration. Her own uneven performance in the job at times led Biden to question her political viability in a theoretical race against Trump.

That race appears to be real, and Biden will be left to hope that Harris is the kind of galvanizing candidate she briefly was during her 2020 campaign, before it unraveled, and that she can convince everyone opposed to Trump to join her. After the party’s experience with Biden, her candidacy comes with big questions. Can she head off a Democratic civil war over its ideological future like Biden did by bringing progressives and moderates together to focus on policy goals and the threat of Trump? Can she convince skeptical voters that she represents steady leadership over Trump’s brand of chaos like Biden did four years ago?

Biden’s presidency is not over. He still has wars in Gaza and Ukraine to deal with, an economy to manage, and a campaign to help as best he can. The way his presidency will be remembered is now, finally, out of his hands.

Source link