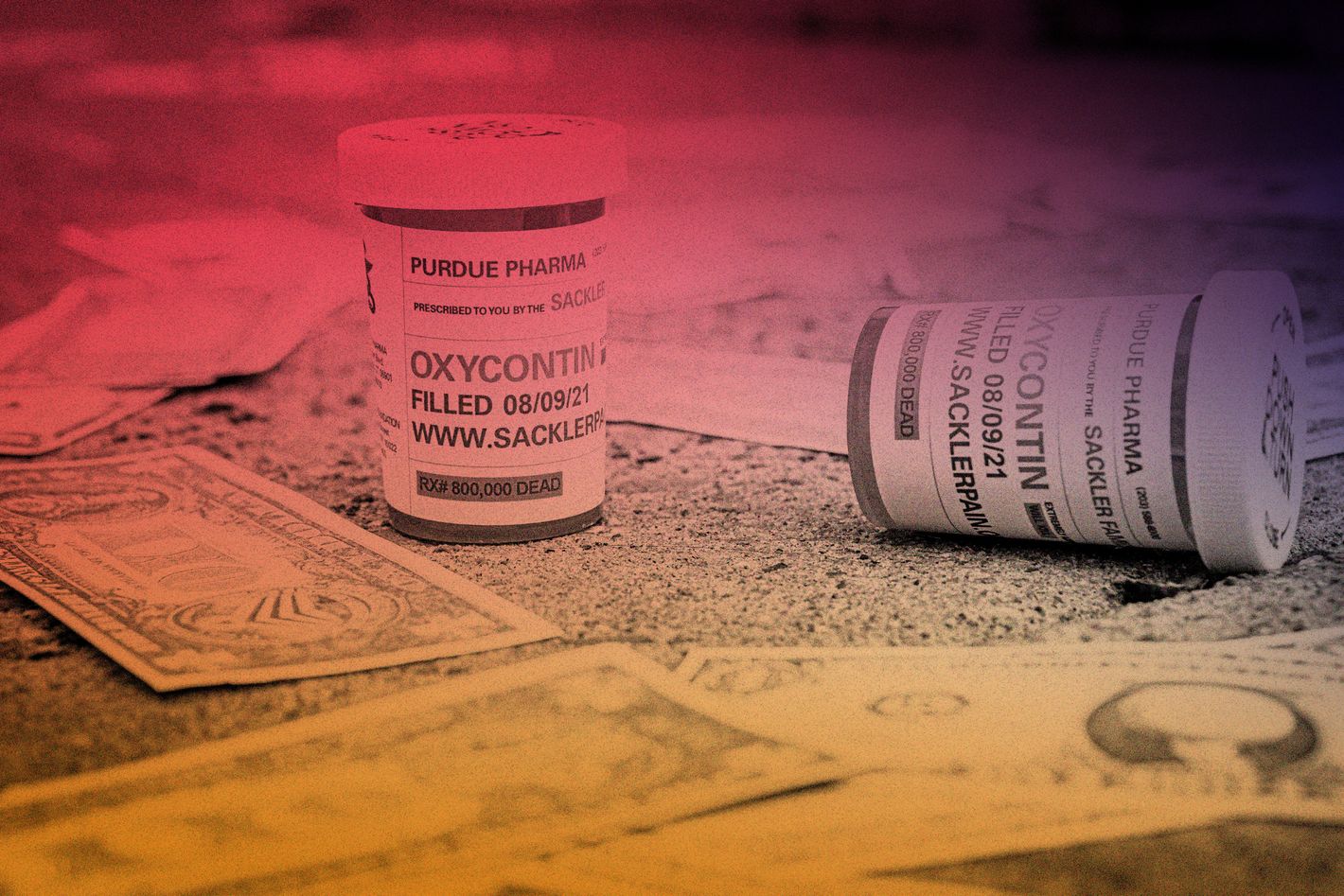

Last week, the Supreme Court threw a grenade into years of painstaking negotiations between the family that helped usher in America’s opioid epidemic and thousands of their victims. In a 5-4 opinion, the Court held that a complex settlement worth as much as $6 billion, and agreed to by oxycontin manufacturer Purdue Pharma, the Sackler family who once ran it, and a long list of plaintiffs including states, tribes, and individuals, could not stand because the Sacklers had improperly used bankruptcy court to shield themselves from civil liability down the road — a key plank of the deal. For victims who had grudgingly signed on to the settlement in hopes that they’d finally see some compensation for their suffering, the ruling — which means they might never see any money at all — hurt badly. For others, more invested in seeing corporate drug pushers face any kind of personal justice, it was a relief.

The journalist Patrick Radden Keefe introduced many Americans to the Sacklers, first in The New Yorker and then in his book Empire of Pain. He chronicled how members of the insular clan, once pharmaceutical and philanthropic royalty, ruthlessly pushed oxycontin with the help of pliant medical authorities and doctors, opening the door to a public-health crisis that continues to exact a devastating toll across the U.S. And his reporting galvanized a backlash that has all turned much of the family into pariahs. I spoke with Radden Keefe after the ruling came down about the Sacklers’ newfound vulnerability to lawsuits, how their crafty financial maneuvering has helped shield them over the years, and whether they feel any guilt or shame over their role in an epidemic.

After the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Sackler family issued a statement in which they said, “While we are confident that we would prevail in any future litigation given the profound misrepresentations about our families and the opioid crisis, we continue to believe that a swift negotiated agreement to provide billions of dollars for people and communities in need is the best way forward.” Knowing what you know about this family, do you think they’ll agree to anything without the benefit of the liability shield?

I think that’s the big question, and you see a difference of opinion between the Court’s majority opinion and the dissent on just that. The majority, somewhat optimistically, says “Maybe there’s a better deal to be made here” — essentially, that the Sacklers had been prepared to put up $6 billion, but that if you withdraw the shield, they may ultimately increase that figure. So that’s one point of view. There’s another point of view you see in the dissent, which is essentially “We don’t know that.” You had $6 billion on the table. It was going to get paid out quite slowly over 19 years, but even so, that money is desperately needed. One of the issues in this case is that a lot of the Sackler money is offshore. So there’s this question of — how would you actually claw that money back if they for whatever reason decide they don’t want to play ball?

I think the danger they’re facing is a lifetime of litigation. It’s hundreds or even thousands of lawsuits they could be fighting ad hoc forever. And it could go on for the rest of everybody’s lives, which is less appealing for victims and people who could use that money in order to help remediate the damage of the opioid crisis, and also less appealing for the Sacklers. So my sense is that they will all go back to the mediation process and try to come up with a version of the deal, which I think probably will ultimately entail more money coming from the Sacklers and may leave open the idea that in the future there are people who can sue them.

Can the Sacklers maintain absolute immunity from lawsuits now under any circumstance? Or is that totally out the window with this ruling?

Some of this stuff is very complicated and technical, but the difference is between a non-consensual third-party release, which is what the Supreme Court said they couldn’t do, and consensual third-party releases, in which basically you get people to waive their right to litigate.

One of the issues in this case is that you have a huge class of people, 80,000 people or something — who have claims that could be brought that we know of. Then there’s a smaller group of people who actually came in and voted on the settlement deal. The majority of the people who voted signed off on it, but the number of voters was a small minority of the overall group of people who could potentially bring claims against the Sacklers. So the challenge is that you have this larger universe of people who might want to sue, might have good grounds for doing so, and didn’t come into the process to sign off on this deal.

I think the discomfort you end up with — and this is what gets expressed in the court’s opinion — is can a bankruptcy judge really say “There will be no future litigation against the Sacklers because we’ve all done this deal,” and foreclose the possibility that some of those other people would be able to bring suits in the future? There may be a version of this in which the Sacklers are able to get some larger number of people to consent to the deal, and minimize the number of outliers. Because the nightmare for the Sacklers is that they pay all the money and then they nevertheless are looking at a lifetime of litigation.

Let’s say some lawsuits do go forward against the Sacklers. Who specifically would be in the crosshairs? Richard and David Sackler come to mind.

We talk about the Sackler family, but in fact, there are three different branches of it, and only two of those branches were involved in the management of the company while it was marketing Oxycontin in a way that we now see as having been dangerous and fraudulent. Richard Sackler was running the company for a period of time. There’s his son David, and Kathy Sackler, his cousin from the other branch who was involved in the management of the company. You ultimately had members of these two different branches of the family from three different generations who dominated the company’s board of directors and were very, very involved in decision-making at the company. That’s all been pretty well established in litigation at this point. So yes, in terms of actual individuals who would be named, I think if there’s a bullseye, Richard Sackler is sitting on it.

To this day, none of these people have ever admitted any fault or really expressed any guilt or shame, is that right?

That’s correct. I think it’s been almost a point of pride for the family. There have been many instances over the years in which the company would settle lawsuits, essentially pay for lawsuits to go away, but never wanted to acknowledge any wrongdoing. The family has been very adamant that they never did anything wrong at all, that this is a false narrative. You saw that in these very dramatic moments in which Richard and Kathy and David got hauled before Congress a number of years ago and testified and were questioned by members of the House. I think people were quite shocked. I was watching it in real time and just the implacability of these people was unsettling. In the context of the bankruptcy deal, it was always very important to the Sacklers that they would make no acknowledgments of responsibility or apologies or anything along those lines. It was part of the deal that, “Okay, we’ll put up the money, but we’re not going to concede the point.”

I wonder if they feel that they’ve been so wronged that this ruling hurts on that level more than the prospect of litigation or any financial penalty.

Oh, that’s really interesting. I think the first thing to say is that the family is not by any means monolithic. So I think there are probably differences of opinion even among the core members who are most implicated in this story. Certainly, Richard Sackler, in terms of his personality profile, has always had a defiantly stubborn streak. He’s getting quite old, and I don’t know that he has the appetite necessarily to fight for the remainder of the years that he has left. But I tell these stories in my book about him incessantly responding to emails to people in the middle of the night who had the nerve to suggest that there was anything wrong with Oxycontin. There was a pride, in his case, where you could see him going down with the ship.

I don’t know that that would necessarily be true for everyone. I think particularly for David, who’s younger — he’s in his 40s and has young kids — and his cousin, Mortimer, Jr., who was also very involved in the business — these are people who I would think are looking at quality of life for themselves over the coming decades and thinking, there has to be some way that I can put this behind me. The reputational cost, I think, is probably just priced in for them.

As you’ve chronicled extensively, their names have been taken off museum wings and other institutions around the world. They’ve become persona non grata in a lot of places. But there are all kinds of shady people who are doing fine financially and living a pretty sweet life, even if they’re getting good ink in the newspapers.

In Florida, yes.

The rogue state.

Which I should say is where Richard and David ended up. The last refuge of scoundrels.

Do you have a sense of the kind of company they’re keeping and whether they’re still welcomed in certain echelons of high society?

A number of them have left New York. It may be that places like Florida or Switzerland present a more commodious alternative for roguish people with dicey reputations and a lot of money. My sense is that even in Florida, there have been instances in which they’ve been shunned. So I think that there is a social stigma that they are going to live with for the rest of their life. But I think the reality is that for a certain segment of society, what matters is money, and they still have it.

The reputation stuff may be priced in, as you said, but their lives could get meaningfully worse if the lawsuits start coming in.

Oh, absolutely, yes. I think that the $6 billion figure is interesting, because it started much lower. For a period of time they were saying, “We’ll commit $3 billion,” and then it went up to about 4.5 and then finally it went up to 6. I think there’s good reason to believe the number will go up more now that the deal has been undone. But you have to remember that this is a family that has a fortune of at least $11 billion, and that they were committing to pay any money out over 19 years, so this is very sustainable for them. It’s a strange thing to say to suggest that $6 billion might not actually be that much money, and I’m sure it’s painful for them to part with it, but it’s a loss that they can sustain.

Listen, I had expected that this case would get ruled the other way. I had thought that they were home free. And I had thought that there might be a dangerous precedent here where the court would essentially ratify the ability of bad corporate actors to create this kind of harm and then just game the bankruptcy system.

That’s all the rage right now. Johnson & Johnson is doing it, the Boy Scouts are doing it…

Exactly.

I was actually a little surprised by the ruling too, because of this court’s usual pro-business slant.

Absolutely, and you get this 5-4 vote, with odd bedfellows on both sides of the decision. I think that just reflects the fact that it’s not an easy case. It’s very, very difficult. The one thing that I wrestled with when I was writing the book and I was covering the bankruptcy process in real time is that the whole idiom of bankruptcy law is all about efficiency and cutting a deal and arriving at the least bad disposition of a situation. It’s very pragmatic. There is a sense, in that pragmatism, that larger concerns like justice and transparency and accountability are almost a little sentimental, that they have no room in a deal. I think you see that conflict playing out in this decision where there are people on the one side who were saying, “That was $6 billion. It was really hard to arrive at that deal with all these different stakeholders.”

It took years and years.

Somebody once memorably described bankruptcy proceedings as a melting ice cube. Those were years in which you had all these bankruptcy lawyers billing $1000 an hour or more, and the sum of money to be distributed was rapidly diminishing because the bankruptcy lawyers cost so much. To one way of thinking about it, the fact that the deal gets set aside now and everybody goes back to the negotiating room means that the sum of money that is there to be distributed will continue to erode, because there’s going to be the huge expense of coming up with some alternative that is viable. But on the other side-of the ledger, there’s this question of justice. Do we really want a situation in which you cut a deal and the bad guys ride off into the sunset?

You implied at the top that it would be difficult to extract all this money from the family. Along with everything else, they’re experts at hiding cash, right?

I agree with that, but I also have to say that during the course of the bankruptcy proceedings and even in the Supreme Court dissent, I always found it pathetic when people articulated that as a reason to make the deal. It always seems so bizarre to me.

Throwing your hands in the air and giving up?

Yeah. Just saying, “Well, Jesus, look at them. They craftily moved all the money offshore, and it’s really only through their indulgence that we could expect them to furnish us with any of that cash at all. So let’s come up with a situation that pleases them.” That seems like a strange position for a judge or a Supreme Court Justice.

But realistically, it is going to be incredibly difficult to get the money.

Yeah, no question. This is a formidably well-resourced family. For people who haven’t followed all the ins and outs of this case and may be wondering, “How is it that Purdue Pharma, the company, ended up in bankruptcy court in the first place?” The whole way we got here is that about a decade before Purdue declared bankruptcy, there were conversations within the family where they realized that this litigation isn’t going anyway, that there are going to be more and more of these lawsuits. They realize that at some point somebody’s going to have to pay the piper. And there are emails among family members saying eventually one of these lawsuits is going to break through to the family. So a decade before the company actually declares bankruptcy, the Sacklers start very quietly siphoning money out of the company and into their private accounts — moving it offshore and making it hard to reach. They take more than $10 billion out of the company. Then when they’ve bled it dry, they declare bankruptcy for the company, not for them.

So I think that’s what you’re up against, is a group of people who had the foresight a decade out to start preparing for the eventuality in which the company that they owned and controlled would be so overwhelmed by lawsuits that it could declare bankruptcy and they could have already pulled $10 billion out of it and kept it somewhere safe.

You’ve got to tip your cap, just on a criminal level.

It’s hard to deny that there’s a fiendish brilliance.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Source link