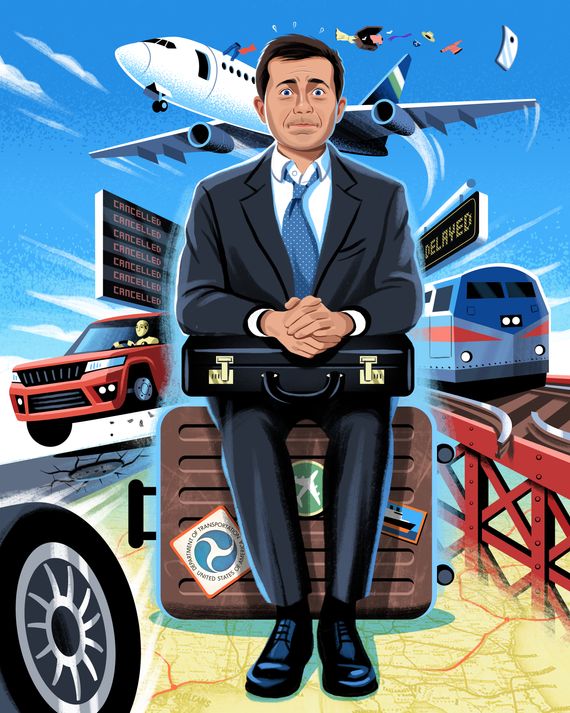

Illustration: Ben Kirchner

The day I met Pete Buttigieg in his Washington, D.C., office in April, his morning had begun with an NPR interview conducted out of a van parked outside his house. His twins, who are not yet three, were up before 6:30 a.m., and their noise had already taken over. The early wake-up left no discernible impact on Buttigieg: He is the same indefatigable person he plays on TV — eerily intense eye contact, emphatic hand movements, crisp bullet points — a role he plays frequently as one of the Biden administration’s most ubiquitous surrogates. As Matthew Yglesias once noted, “The Secretary of Appearing on Television continues to be excellent at his job.”

Buttigieg’s actual job, though, is secretary of the Transportation Department, which is currently overseeing a series of overlapping crises. In late 2022, Southwest Airlines melted down, canceling nearly 17,000 flights smack in the middle of holiday travel, the largest airline disruption in U.S. history. In early 2023, an FAA outage grounded all domestic departures, leading to more than 1,300 cancellations and over 10,000 delays. Around that time, a freight train derailed near the town of East Palestine, Ohio, and spewed toxic fumes into the community’s air and soil. Meanwhile, about 100 people die every single day in car crashes on American roads. And this year, part of a Boeing plane fell off in midair, sucking passengers’ clothing out of the gaping hole and bringing scrutiny to a company that has allegedly cut corners with little blowback from the government. It would seem like an ideal moment to have a young, ambitious, famous politician at the head of an agency that has long been led by anonymous bureaucrats and captured by the industries it nominally regulates.

The large conference table we sat at was littered with Notre Dame coasters from the university adjacent to South Bend, Indiana, the town where Buttigieg was elected mayor at age 29. Military medals and regalia were stacked along a table behind him; Buttigieg served as a naval reservist and was deployed to Afghanistan for seven months in 2014. His desk was adorned with photos of his kids and his husband, Chasten Buttigieg. (There were no visible trinkets from his multiyear stint as a consultant at McKinsey & Company.) Contained in these objects is Buttigieg’s political persona: a patriotic climber who broke barriers as a gay man; a Harvard graduate and Rhodes scholar who devoted the early part of his career to fixing potholes in his hometown; a show horse and a workhorse all in one.

He entered Transportation on a wave of optimism about what he might do. “I had such high hopes for him,” said Loretta Alkalay, an aviation lawyer and adjunct professor at Vaughn College of Aeronautics and Technology. “He was not necessarily who we had picked,” said Greg Regan, president of the Transportation Trades Department at the AFL-CIO, but Regan was excited about having “a political celebrity running our little part of the world.” As Buttigieg nears the end of his first and quite possibly only term, however, the high hopes have dimmed. “He has a lot of power,” said John Goglia, a former member of the National Transportation Safety Board and professor at Vaughn. “He really hasn’t used his influence.”

Buttigieg has pushed through some changes to protect airline passengers’ rights as well as to improve road and rail safety. But he didn’t fully spring into action until recently, even as the transportation sector was in desperate need of systemic change. “It’s been a slow start,” said Senator Elizabeth Warren. That means some of what he has proposed is at risk of never becoming reality, while plenty of other options to transform the sector languish untouched.

Buttigieg described taking a deliberative approach to staking out his agenda. As South Bend mayor, Buttigieg told me, he had announced a safe-streets initiative early on “and we got clobbered,” he said. “People hated it.” He had to expend a lot of his political capital to get it through, and the slow pace made for a frustrating experience, he explained. At the outset of any four-year term, he said, there are two approaches: “What you have to do is either lay groundwork that won’t pay off for a while or deploy capital and upset people in order to get things done.”

At Transportation, he opted for the first approach, lying low at first instead of muscling through aggressive reforms. More than once, he told me he wanted rules and directives to be “bulletproof” when leaving his office. “It’s got to be really tight, which means it takes time and money and people to get it done,” he said. Two new consumer rules designed to protect fliers, finalized in April, are crowning achievements, but they weren’t started until at least a year into his tenure.

As a 42-year-old who has already run for president, Buttigieg, unlike most of his predecessors at the department, is clearly going somewhere after his role at Transportation. His future in politics may depend, in part, on how people will judge his performance at his biggest job yet and how they will view what critics call his inexperience and his timidity in the face of powerful corporate players. Because Buttigieg has another political persona he has long sought to shake — one whose caution is more associated with calculation than prudence and whose vaulting ambitions have outpaced actual deeds.

What you make of Buttigieg’s tenure may depend on your point of comparison. He has run laps around his predecessor, Elaine Chao — a “nonentity,” according to Peter DeFazio, a former House representative who spent his entire career on the Transportation and Infrastructure Committee. He has also gotten more done than other secretaries, most of whom were bureaucrats from the transportation sector or were meant to represent the bipartisan bona fides of a president’s Cabinet. (Ray LaHood, anyone?) “Secretaries of Transportation often don’t enact transformative changes,” noted Eric Dumbaugh, associate director of the Collaborative Sciences Center for Road Safety.

But as Congress has come to accomplish less and less, what the executive branch can get done on its own means more and more. (The Railway Safety Act, put together in the wake of the East Palestine derailment, has sat for over a year without a vote.) Many in the Biden administration have taken this lesson to heart. Lina Khan at the Federal Trade Commission and Jonathan Kanter, head of the Antitrust Division at the Department of Justice, for instance, are completely redoing the merger-review process in a bid to prevent monopolies from forming. Khan has also banned noncompete agreements and pursued a number of companies, including Amazon, for harmful practices. Rohit Chopra at the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau has doggedly gone after junk fees, overdraft fees, and tech companies pushing their way into banking. National Labor Relations Board general counsel Jennifer Abruzzo has aggressively pushed the limits of workers’ rights. Richard Revesz and K. Sabeel Rahman turned the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs, which had for decades been used to thwart government regulation, into a place that now facilitates it.

Khan, in particular, “started with one idea after another on how to fight” corporate concentration, Warren noted. “Pete did not have an obvious focus when he came in, and it’s taken him longer to get his feet under him on the big competition issues.”

Buttigieg didn’t begin the job with a wealth of knowledge about the country’s infrastructure. He essentially went straight from being mayor of South Bend to his current role with his presidential campaign and some political fundraising in between. It took some getting up to speed. “The scope of the department is so complex that I’ve spent much more time just navigating my own organization or figuring out what these tools even were compared to the relatively nimble creature that is a city administration,” he told me. “I’m still obviously very much learning as I go.”

Early in his tenure, he told DeFazio he was using the COVID lockdowns to learn. “He said it’s like a very intense graduate Ph.D. program,” DeFazio said. Senator Tammy Duckworth, who has worked with Buttigieg on making American transportation more accessible for people with disabilities, said he has “not been shy about listening to others who have more experience.”

But learning on the job eats precious time when you have inherited transportation sectors that are in acute crisis — none more so than the airlines. In addition to frequent cancellations and delays, fees keep getting tacked on for basic needs and planes keep getting more crowded. Airlines still appear to offer flights they know they don’t have the staff to actually fly, there have been reports of regular near-collisions likely caused by a lack of air-traffic controllers, and Boeing alone seems to make headlines every other week for emergency landings and faulty parts. “It’s never been more frustrating to be an airline passenger than it is today,” said John Breyault, vice-president of public policy at the National Consumers League.

Even before the disastrous 2022 holiday flying season, 38 state attorneys general accused the DOT of failing to “respond and to provide appropriate recourse” regarding the pile of consumer complaints they were receiving about airlines, and Senators Warren and Alex Padilla urged Buttigieg to use his authority to “protect consumers and promote competition” as cancellations and delays grew worse.

When it comes to airlines, the secretary’s actions hold outsize power. That’s because after airlines were deregulated in 1978, Congress preempted state and local authorities from regulating them and consumers can’t file state lawsuits. “If Pete Buttigieg doesn’t do something, then it doesn’t get done,” said William McGee, senior fellow for aviation and travel at the American Economic Liberties Project. Not to mention that airlines don’t tend to listen to suggestions. “Unless you absolutely grab them by the collar and sit them down and say, ‘This is what you have to do,’ they will not do it,” McGee said.

The Southwest meltdown finally spurred the department to action. It hit the airline with a $140 million fine, which was 30 times bigger than any other penalty the agency had levied against an airline, and pressured Southwest into refunding disrupted passengers $600 million. In comparison, the department issued less than $71 million in fines between 1996 and 2020, according to a DOT spokesperson.

The Boeing debacle also shook the department. In response, the FAA, which is housed in Transportation and has long been viewed as a tool of the industry, grounded some Boeing 737 Max 9 planes so they could be inspected. Days later, the agency announced that it was investigating the incident, “which is a change” from how previous DOTs have handled similar cases, said McGee. It has since put more inspectors in Boeing’s Renton, Washington, facility and halted production expansion of the 737 Max.

Buttigieg has stepped in to prevent further airline consolidation, which critics say allows companies to make life more miserable for fliers. In 2023, he came out against the proposed JetBlue and Spirit Airlines merger, the first time the department has gone against a merger since deregulation. This demonstrated, Buttigieg told me, that “we in fact were willing to pick up these tools, the competition authorities, that had been here the whole time.”

The final consumer rules announced in April are at the top of his list of accomplishments. The first will require airlines to automatically and quickly give passengers cash refunds when flights are canceled or significantly delayed as well as when any services they paid for don’t materialize, such as Wi-Fi that won’t connect or checked bags that never show up. The second goes after junk fees by requiring airlines to tell people upfront what fees they will face, instead of tacking them on toward the end of the process or when they show up at the airport. (Airlines have already sued to block it.)

Buttigieg also proudly talks up the creation of a dashboard he released in late 2022, which made public the customer-service commitments of ten large airlines. The agency has said that all but one of the airlines improved their service commitments in response, and the DOT can now enforce the promises. “That wasn’t an exercise of power, it was not a rulemaking, it was not an enforcement action,” Buttigieg noted. The flipside of that, of course, is that nothing requires airlines to stick to these policies in the future.

For some, these achievements go only so far. Warren praised the secretary for coming out against the JetBlue-Spirit merger. “But we need to do a whole lot more,” she said. Buttigieg has plenty of tools to improve flying that are still sitting untouched. McGee and Vanderbilt University law professor Ganesh Sitaraman recently released a paper succinctly titled “How to Fix Flying.” Although it’s aimed primarily at Congress, about a quarter of the proposals fall squarely in Buttigieg’s lap. When McGee met with him to go over the recommendations, “We said rather bluntly, ‘Some of this stuff is rather low-hanging fruit,’” he said.

In the waning hours of the Trump administration, the DOT issued a rule restricting its own authority to go after the airline industry for unfair and deceptive practices. While Buttigieg issued a reinterpretation of the rule, he never fully rolled it back, potentially allowing the airlines to, for example, gum up the works on rulemaking. “I don’t think it has undone the damage,” Breyault said. (A DOT spokesperson pointed out that the agency was able to finalize its recent consumer protections with the Trump-era rule in place.)

Airlines know with near certainty their crew and plane capacity at least six months in advance, according to McGee. Allowing people to book flights that get canceled a week or two out raises questions about whether the airlines had ever planned to fly them in the first place. So Buttigieg could use his authority to go after them for what is almost certainly fraudulent behavior, just as Australia recently went after Qantas. Buttigieg says the agency is in fact doing this, but nothing has been announced yet. “We’re doing specific investigative actions on unrealistic scheduling, but they can be very hard to demonstrate,” he told me.

He could use the same powers to potentially regulate frequent-flier programs so they can’t change the value of points or other terms on a whim or to ensure that big airlines don’t squat on airport gates or landing and takeoff slots, elbowing out smaller and low-cost carriers. “Pete could put a stop to that now,” Warren said. He could require airlines to maintain 24/7 call centers.

Priority No. 1 for safety is ensuring that the FAA fills its head count for air-traffic controllers and other safety-related positions, which has been lagging for years. “He needs to prioritize those safety positions and keep the numbers very close to maximum,” Goglia said. The DOT spokesperson pointed out that after many years of declining, head count for certified professional controllers rose by 325 between 2020 and 2023, and the agency is planning to hire a record 1,800 this year.

He could require infants under the age of 2 to be put in car seats in their own ticketed seat; currently, airlines allow infants to be carried loose on someone’s lap. If a plane has to suddenly stop, “you just can’t hold on to the kid,” Goglia said; the baby will go flying through the aircraft — a possibility underscored by the recent death of a man on a flight that had experienced extreme turbulence.

Some rules Buttigieg has pursued to protect airline consumers still aren’t finalized, and if the process drags out much longer, they risk being rolled back or never even seeing the light of day. The specter of the Congressional Review Act, which allows the next Congress to roll back rulemaking, draws near; the DOT had given itself a deadline of April 30. The unfinished business includes banning fees for family members to sit next to one another, mandating compensation and amenities when flights are delayed or canceled, and expanding the rights of people who use wheelchairs. The comment period on the latter rule doesn’t close until June 12, making its future quite uncertain.

Four years go by quickly, and waiting to get aggressive halfway through makes it hard to accomplish changes that won’t go up in smoke when the next Congress and the next administration roll in. Buttigieg himself has acknowledged that the compressed timeline means he’s now in a “sprint” until November to get things done. “There’s always going to be a set of things that are not on the list,” he told me. “But the list we’re working with is pretty good.”

For all the airlines’ problems, the most recent fatal crash happened in 2009. In comparison, an estimated 40,990 people died in car crashes last year, enough to fill more than 186 Boeing 787 Max 9’s. “Road safety is a massive problem; it is a crisis,” said David Harkey, president of the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety. These deaths make the U.S. an extreme outlier. The American crash death rate in 2019 was the highest among 29 other high-income countries; 22 of those countries drove their rates down while ours increased.

Buttigieg and his staff repeatedly pointed out that there has been a decline over the past two years. “We’ve reversed the rise in roadway deaths,” he told me, though he acknowledged it was “only just” so. The drop has been in the single digits after a double-digit increase in 2021. Deaths per vehicle miles traveled are still higher than they were before the pandemic.

As with the issue of housing scarcity, the power to make changes mostly lies in the hands of state and local governments. But the DOT controls some purse strings and sets standards.

This is the area Buttigieg came in knowing the most about. “Mayor Pete was amazing,” said Charles Marohn, president of the Strong Towns nonprofit. “There was no one better.” As secretary, he has adopted a “complete streets” approach favored by advocates that prioritizes safety for all road users, not just cars, in his National Roadway Safety Strategy, and he said from the beginning that he wanted to aim for zero vehicle fatalities, an ambitious and novel goal for the agency. Still, that “was the easy part,” Harkey pointed out. “The hard part now is implementation.”

Within the confines of the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law, which Buttigieg helped fight for and was passed in November 2021, the DOT has put aside discretionary grants for street safety, though it’s a drop in the overall bucket — $5 billion out of about $1 trillion. In late April, the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which is also under the DOT, released standards that, by fall of 2029, will require new cars to have high-speed automatic emergency brakes that bring them to a stop to avoid crashes with other cars and pedestrians.

“He’s put out a vision, and that’s great,” said Robert Schneider, co-chair of the Department of Urban Planning at the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee. “It’s even more to deliver.”

A major step Buttigieg could take on his own would be to change federal vehicle-safety standards. Car manufacturers have made huge strides in protecting people inside cars in a crash, but currently, the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards do nothing to reduce the risk to people outside like pedestrians and cyclists. The same is true of NHTSA’s safety ratings from crash tests. Its New Car Assessment Program’s five-star rating for the safest possible cars can be changed to take into account the risk to people outside the cars. According to the DOT spokesperson, NHTSA is in the process of making “significant updates” to NCAP and has requested public comment on adding pedestrian protections.

NHTSA can also “be more aggressive,” Harkey said, in requiring lifesaving technology as standard, not an add-on. Instead of American cars getting increasingly heavier and larger, standards could dictate sizes that reduce fatalities and the inclusion of things like aprons on hoods to make sure that if a pedestrian is hit, they go over and not under a car.

The Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices, originally a guide for street signage, today dictates much of road and street design and has typically focused on how to move cars quickly. Buttigieg oversaw the release of a new version at the end of last year that has some important changes, but it still, for instance, requires cities to wait until people are hurt or killed (or for a large volume of people crossing) before crosswalks can get signals, includes rigid rules for bike lanes, and demands that pedestrians and cyclists always act “reasonably and prudently.”

The East Palestine derailment, when 38 cars of a Norfolk Southern freight train went off track in February 2023 releasing toxic chemicals next to a community of 4,700 people, turned a scorching spotlight on rail safety. Derailment rates had been falling for many years, but they have flatlined for the past decade and now hover around three derailments a day. Many of those trains carry hazardous substances, and more than two-thirds of derailments happen near cities. “The needle’s not swinging appropriately,” said Gary Wolf, who owns Wolf Railway Consulting.

Buttigieg was on the scene at East Palestine, though he caught some flak for showing up nearly three weeks after the incident and, worse, a day after Donald Trump. In the aftermath, he has steadfastly pushed for the Railway Safety Act that’s currently stalled in Congress. Meanwhile, the Federal Railroad Administration has conducted tens of thousands of inspections of cars and tracks and increased its safety penalties. Buttigieg sent a letter to the president of the Association of American Railroads saying he considers the current rate of derailments “unacceptable.” He also said the DOT is “using every tool we currently have.”

In early April, he announced the finalization of a rule first proposed under the Obama administration to require two-person crews on most trains, particularly as they grow longer and longer, and in May he finalized rules to certify train dispatchers and signal employees to ensure they can do their jobs safely. The FRA has also finalized Obama-era proposals to require video recorders on the front of passenger trains and mandate that large railroads identify and address fatigue in their systems. Under Buttigieg, the FRA levied $17.3 million in civil penalties against Class 1 railroads last year, a record high.

But both Wolf and Constantine Tarawneh, director of the University Transportation Center for Railway Safety, argued that an important safety improvement would be to encourage rail companies to use onboard sensors to detect problems with bearings, wheels, and tracks, a technology they say would enhance safety beyond current sensors along the sides of tracks and manual inspections. It would be a huge and expensive undertaking. “If it’s not mandated by Congress, and there is no incentivization by DOT, there is no reason for them to adopt,” Tarawneh said.

Buttigieg could also require railroads to participate in the confidential close-call reporting program that allows employees to report possible dangers free of disciplinary repercussions. Buttigieg called on railroads to join immediately after East Palestine; they all vowed to do so, but only two major railroads have.

“We’ve squandered an opportunity the last four years to really push the needle forward on rail safety, and it’s just stagnated,” Wolf said.

The Department of Transportation is an enormous ship to turn around. From its inception, it has been one of the more captured agencies. It was given a dual mandate for airlines: to both oversee and promote the industry. That mandate was rescinded decades ago, but “the mind-set persists,” McGee said. Longtime staff tend to look backward, relying on past precedent. “There is tremendous inertia in the bureaucracy of the DOT, which is hard for any secretary to overcome,” DeFazio said. “Secretaries come and go, but the bureaucrats are going to be there.”

There are also certainly many moneyed, powerful interests who would prefer a weak DOT and secretaries who do little. The transportation sector has long been among the top-ten spenders in Congress. The airline industry holds huge sway on Capitol Hill; as one small example, it was the only industry that managed to exempt itself from new workplace breast-pumping rules. “They toss a lot of money around and often get what they want,” McGee said.

Changes to roads and railroads are no less controversial. After the Federal Highway Administration issued guidance — which didn’t even have enforcement power — urging states to use money from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to fix and maintain roads before expanding them, Republicans erupted in outrage, forcing the agency to backtrack. The railroad industry enjoys lobbying firepower while frequently remaining out of the public eye. Even Norfolk Southern has reportedly joined the lobbying effort to stymie the Railway Safety Act while publicly saying it supports safety improvements. The lobby “punches way above its weight,” DeFazio said. “Republicans are totally in the pocket of the freight-rail industry, as well as apparently many Democrats.”

“The industry has had its way with Washington for decades now, and it doesn’t like anyone who comes in and upsets that,” Warren noted. “It’s the hard path to take. It’s so much easier in the agencies just to go along with the industry.”

Transportation secretary is not typically a perch with a lot of prestige, and it doesn’t tend to launch careers. Secretaries also don’t usually stay for more than a single term, so even if Biden wins in November, it’s likely Buttigieg will soon be on to something else, though it’s unclear what that will be. When he moved his family to Michigan in 2022, tongues wagged that it was to position himself to run for office there, but he didn’t jump into the scrum after Senator Debbie Stabenow announced her retirement earlier this year. Buttigieg told me he doesn’t know what comes next for him. “But you are always shaped by what you’ve been doing,” he said.

There’s almost certainly a ton of political hay to be made from being the person who fixed flying, so leaving so many actions untouched is puzzling. There may be less political payoff in other areas. It’s unclear whether Americans really want to change our roads and streets to prioritize safety over speed, and industry firepower weighs against bold action. “Politically, do you want to take on the automobile industry?” Dumbaugh said. “Particularly when somebody is perhaps looking for another elected office, I’m not sure the political will exists.”

Maybe Buttigieg has played his hand the only way he could: by carefully deploying the agency’s resources and firepower to garner the most effective impact. Maybe it is unrealistic to expect anyone to fix these broken sectors in one four-year term. And maybe he has set the Transportation Department on the path to a different future, rescuing millions of people from the dangers and headaches of travel in the U.S. In May, he told an audience his goal is to “be able to say that this administration ushered in the biggest expansion in transportation consumer-protection enforcement and passenger rights since the deregulation era began.” The question is whether the reforms he has accomplished will last and whether Buttigieg — and voters — will look back and say he did all he could to protect American travelers.