Twelve New Yorkers will judge the city’s infamous native son.

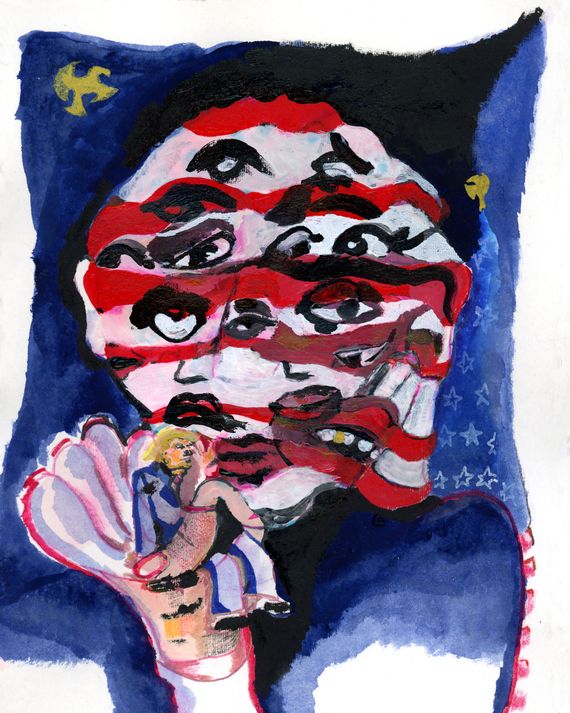

Art: Isabelle Brourman

Midway through his summation for the jury in history’s first trial of an American president, Todd Blanche returned to where the prosecution’s crime narrative began. “The Access Hollywood tape is being set up in this trial to be something that it is not,” referring to the recording that at one time — so long ago now — upended a Donald Trump campaign by showing the voting public the kind of man he was when he thought the cameras were turned off. “It was not a doomsday event,” Blanche went on, contradicting collective memory, not to mention numerous witnesses at the trial, who testified that it set off a frantic damage-control effort, which culminated in a hasty deal to pay off a porn star who was shopping a tawdry story.

As his lawyer spoke, the beneficiary of that deal, the defendant, sat perpendicular to the defense table, directly facing the jury, his eyes wide open, his chin set at an upturned angle. When Blanche tried to advance an innocent motive — his client was being extorted, he said, and wanted to protect his family — Trump swiveled his head and looked directly at his children Tiffany, Eric, and Don Jr., who were sitting in the front row. Otherwise, though, he fixed his gaze straight ahead, sizing up the 12 people who would decide the verdict.

For the past six weeks of the trial, the press in the courtroom gallery has kept its eyes obsessively on Trump. When he closed his eyes and appeared to nap on the first day of jury selection, it burned up the cable airwaves and inspired a million memes: the yawn heard round the world. Since that first day, most of the reporters in the room have acquired small binoculars, which allow us to closely observe him throughout the proceedings. When he passes the time by reading polls and news clips, we try to peer over his shoulder. When he mutters, we point our spyglasses at the TV monitors that show his face and strain to read his lips. When he bats Blanche on the shoulder, we try to guess what injustice he is complaining about now. When he walks out into the dim courtroom hallway during a bathroom break, a penned pool of reporters and photographers records whether he waved, or gave a thumbs-up, or shook a fist.

Maybe, all along, we’ve been looking in the wrong direction. Through the weeks of lurid testimony, and dustups between the defense and the judge, and the contempt citations, and special guest appearances by vice-presidential hopefuls, the jurors sat there like birds on branches. Their names are being withheld from the public in order to protect them from the harassment — or worse — that could come at them as a result of their decision, but watching them in the courtroom day after day, you could observe their plumage. Juror 1, the foreman, who favors tight T-shirts and has a face that sits in a resting smirk; Juror 3, a young lawyer with structured hair, who tried to grow a beard for a while and then gave up; Juror 12, an Upper East Side woman, who wore a white shirt and sweater for closing arguments. A suffragette signal, or was it seasonally appropriate for the day after Memorial Day? Looking through the binoculars, a birdwatcher can’t tell you what the birds are thinking. But you can try to surmise the direction they’re migrating.

As Blanche continued on, turning his attention one more time to Stormy Daniels, the woman who was paid $130,000 to shut up and didn’t stay bought. “Why did they call her as a witness at trial?” said Blanche, hinting at the defense’s anger at her testimony, which they found to be gratuitously graphic and prejudicial. “I’ll tell you why,” Blanche said. “They did it to try to inflame your emotions. They did it to try to embarrass President Trump.”

At this moment, I turned my binoculars on Juror 5, a young Black woman who wears her hair in braids. She is a schoolteacher and sits with classroom posture. During jury selection, she gave the defense some persuadable signals. (“President Trump speaks his mind,” she said, in response to a question about her opinions about his presidency, though she also added there was “a divide in the country, I can’t ignore that.”) But as Trump’s lawyer attacked Stormy Daniels’s credibility, Juror 5 wore a thin smile, looking like she was about to call a disobedient child up to the chalkboard. I swiveled my binoculars to Trump. He was making that purse-lipped expression he uses to convey contempt when he’s on a debate stage.

From the beginning, Trump has stood little chance of winning an outright acquittal on all 34 felony counts of falsifying business records. The prosecutors of the Manhattan district attorney’s office have done a masterful job of laying out the evidence that Trump’s attorney, Michael Cohen, arranged the payoff to Daniels after the Access Hollywood tape emerged and then accepted reimbursement from Trump for the expense after the election in the form of a series of payments disguised as a legal fees. As I wrote in an April cover story, during jury selection, Trump’s best hope has always been to convince one or more holdouts to hang the jury. A mistrial, for Trump’s political purposes, would be just as good as an acquittal. So all along, his legal team, his supporters in the gallery, and the press have been watching the jury box for any signal, however subtle, that the defense is making inroads.

Blanche’s closing argument went on for more than two hours, but it essentially boiled down to a single word. “Cohen lied to you,” he told the jury of the prosecution’s key witness. He repeated some variation of that phrase more than 60 times in the summation. He called Cohen the “MVP of liars” and later “the G.L.O.A.T.,” or “greatest liar of all time.” He told the jury that Cohen had lied to Congress, lied to prosecutors, lied to banks, lied to the Federal Election Commission, and lied to Trump, his client, whom he surreptitiously taped and admitted stealing from by taking reimbursement for a second expense that was larger than the sum he really paid. Blanche said he had caught Cohen in a lie on cross-examination, when he called into question whether a phone call Cohen had made to Trump’s bodyguard in October 2016 had to do with a teenage prankster, rather than Daniels.

“That is per-jur-y!” Blanche exclaimed. “You cannot send someone to prison …”

“Objection,” said prosecutor Joshua Steinglass.

“You cannot convict,” Blanche corrected, “somebody based upon the words of Michael Cohen.”

When the jury filed out of the room for lunch shortly afterward, Steinglass rose to address Judge Juan Merchan about what he called the “ridiculous comment” on prison. It’s a rule of lawyering that defense attorneys are not allowed to reference punishment before a jury. “That was a blatant and wholly inappropriate effort to cull sympathy for their client,” Steinglass said.

“I think that saying that was outrageous,” Merchan said, telling Blanche to “have a seat.”

“You know that making a comment like that is highly inappropriate,” Merchan said. “It’s simply not allowed. Period. It’s hard for me to imagine how that was accidental in any way.”

It was, to the very end, a defiant defense — one that appeared to be directed as much by the political dictates of Trump’s campaign as the legal best interests of the defendant.

When the jury returned from lunch, Merchan gave what is known as a “curative instruction,” telling the jury that the reference to prison was “improper and you must disregard it.” Juror 4, a bearded resident of the West Village who said he was into metalworking as a hobby during jury selection, nodded attentively. It is a truism among attorneys that juries view judges as paternal figures, who not only guide their thinking on the law but control their comings and goings and even their eating schedule. Attorneys cross them at their peril. This jury has been particularly diligent throughout the proceedings. One woman, Juror 9, expressed misgivings on the day of opening arguments about the possibility of her identity being exposed to the press. She has stuck it out. Not one juror, in fact, was replaced by an alternate during the trial.

They are a group of people who look much like their borough. Seven are men; five are women. They are well educated: Seven of them have masters degrees, law degrees, or doctorates. One of them is Black; two appear to be East Asian. One was born in Lebanon. The foreman, a salesman, is originally from Ireland. Thus, when (or if) this New York City jury comes to a verdict, it will be delivered to Trump, appropriately, in an immigrant’s accent.

“Mother Theresa could not beat those charges,” Trump said to reporters on Wednesday morning, setting expectations low for jury deliberations. “But we’ll see.” If his defense attorney sought to sprinkle reasonable doubt around the jury box, the lead attorney for the DA’s office, Steinglass, brought a fire hose to his summation. He started off by addressing the lies Cohen admitted to telling in the past. “Just ask yourselves whether they cause you to outright shut your ears to anything else that he has to say,” Steinglass said. He pointed out that one of the lies that Cohen had been prosecuted for, his false testimony to Congress, had to do with Trump’s real-estate deals in Russia. “He got no benefit from that other than staying in the good graces of the defendant,” Steinglass said. For Trump to blame Cohen for that now, he said, is “what some people might call chutzpah.”

Steinglass addressed these issues in a relaxed and conversational tone, as if the prosecution had nothing to fear — and maybe it was all a little amusing. Referring to the disputed bodyguard call, he said, “The defense says, ‘Aha, that’s per-jur-y,’” ridiculing Blanche’s theatrical locution.

Juror 3, the young lawyer, who occasionally breaks the fourth wall with ironic looks at the gallery, appeared to be suppressing a snicker. Then the prosecutor embarked on a courtroom improv routine, playacting the way Cohen might have addressed both the prank-call issues and the Daniels hush-money payment in the 90 or so seconds that the call lasted. “These guys know each other well,” he said. “They speak in coded language. And they speak fast.”

Then, Steinglass turned to a classic argument that prosecutors invoke when challenged on the credibility of their cooperators. “We didn’t choose Michael Cohen to be our witness,” Steinglass said. “We didn’t pick him up at the witness store. The defendant chose Michael Cohen to be his fixer, because he was willing to lie and cheat on Mr. Trump’s behalf.” He pointed out that Cohen was cross-examined for three days, and Blanche “asked him maybe an hour’s worth of questions that had anything to do with the allegations in this case.” At this, I saw Juror 2 nodding what appeared to be agreement.

Some people in the courtroom—and maybe more so, commentators on social media—have suggested that Juror 2 might be a prospect for the defense. He is a white investment banker, who appears to be going prematurely gray. He follows Trump on social media. He appears to occasionally make eye contact with the defendant. On the other hand, Juror 2 has also said he follows Michael Cohen on X, not to mention the person who makes the podcast Mueller, She Wrote, which chronicles Trump’s legal troubles. He said he reads “basically everything.”

Other birdwatchers had their eyes on Juror 7. He’s a balding white collar attorney who lives on the Upper East Side. He sits there every day with a big legal pad on his lap, taking down notes and wearing a severe expression. When his number was called to serve on the jury, according to a pool observer in the courtroom, “he inhaled deeply.” Some legal analysts in the courtroom theorize he could end up driving the jury’s deliberations. For all the salacious underlying facts, the charges that Trump faces—34 counts of falsifying financial documents—are technical, and depend on a complicated theory of intent to commit a larger, unspecified, crime. During jury selection Juror 7 said that he had an “ambivalent” opinion about Trump, but he takes the law and “judges’ instructions very seriously.”

What could that mean? Depends on how strong you think the legal theory is in this case.

“A lot of people say this: Who cares?” Steinglass said. “Who cares if Mr. Trump slept with a porn star ten years before the 2016 election?” But he contended that, despite surface appearances, the crime Trump committed was serious. “It’s harder to say that the American people don’t have the right to decide for themselves whether they care or not, that a handful of people sitting in a room can decide what information gets into those voters’ hands.”

Trump shook his head slightly, and in the row in front of me, his legal spokesperson Alina Habba exchanged a sarcastic glance with the Trump Organization’s general counsel, Alan Garten. The rest of that day’s roster of Trump retainers—his kids, his personal aide, his lawyer Boris Epshteyn, New York real estate pal Steve Witkoff—were staring down at their phones. During a break, Trump offered a terse review of the show, sending out a pair of single-word posts on Truth Social: “BORING!” and “FILIBUSTER!”

Still, the jurors paid heroic attention. Steinglass apologized for “trading brevity for thoroughness,” but really, exhaustion seemed to be part of his strategy. He wanted the jurors to feel the immensity of what he called his “mountain of evidence.” He displayed quote after quote from Trump’s books, in which he described his parsimony and his attention to detail. He went through call logs showing the web of contacts between the players in what he described as a “conspiracy” to corrupt the 2016 election. “Davidson to Cohen,” he said. “Pecker to Cohen. Cohen to Pecker. Pecker to Cohen. Davidson to Cohen. Pecker to Cohen. This is all in a half hour.” He showed what he called his “smoking guns,” a pair of handwritten notes taken by Trump Organization employees that outlined Cohen’s reimbursement. Steinglass took on the defense’s contention that Trump, as president, was really paying him for legal services.

“The testimony was that he did less than ten hours of legal work that year,” he said. “Based on everything that Mr. Trump has said and done, do you think that there is any chance, any chance that Trump would have paid $42,000 an hour for legal work by Mr. Cohen?” He tried a joke. “He was making way more money than any government job would ever pay,” the prosecutor said. “And don’t I know that.” Juror 11, a woman in glasses and a beige blazer, rewarded him with a laugh. During jury selection, Juror 11 said she didn’t like Trump’s “persona, how he presents himself in public,” and said he seemed “very selfish and self serving,” something she didn’t appreciate “in any public servant.” It’s a safe bet she’s not a vote for the defense.

As the day turned to dusk, and Steinglass entered his fifth hour of argument, even the court reporter started to show signs of fatigue. When she asked Steinglass to repeat a phrase, he replied, “beating a dead horse.” The stenographer nodded yes and rolled her eyes. Juror 2 took a glance at the hands of the clock above the courtroom doorway. Judge Merchan had set a deadline of 8 pm, and the minutes were ticking down. Steinglass—who has seemed nothing if not prepared during the trial—appeared to be rushing, flipping pages in a binder, as if it signaled there’s so much more. “Everything that Mr. Trump and his cohort did in this case was cloaked in lies—lies!” he said, going for his own closing flourish. “The law is the law and it applies to everyone equally. There is no special standard for this defendant. Donald Trump can’t choose someone during rush hour on Fifth Avenue and get away with it.”

“Objection,” Blanche said.

“Sustained,” said Merchan.

Nonetheless, Steinglass had managed to say the words get away with it. For decades, as a housing developer, a self-proclaimed billionaire, an unapologetically sexist celebrity, a birther conspiracy theorist, and twice-impeached, four-times indicted president of the United States, Trump has gotten away with it so many times. Here, the prosecutor seemed to be saying to this group of twelve anonymous, emblematic New Yorkers, was a chance to finally hold Trump accountable. They are now deliberating. We will soon learn which way they fly.

Source link